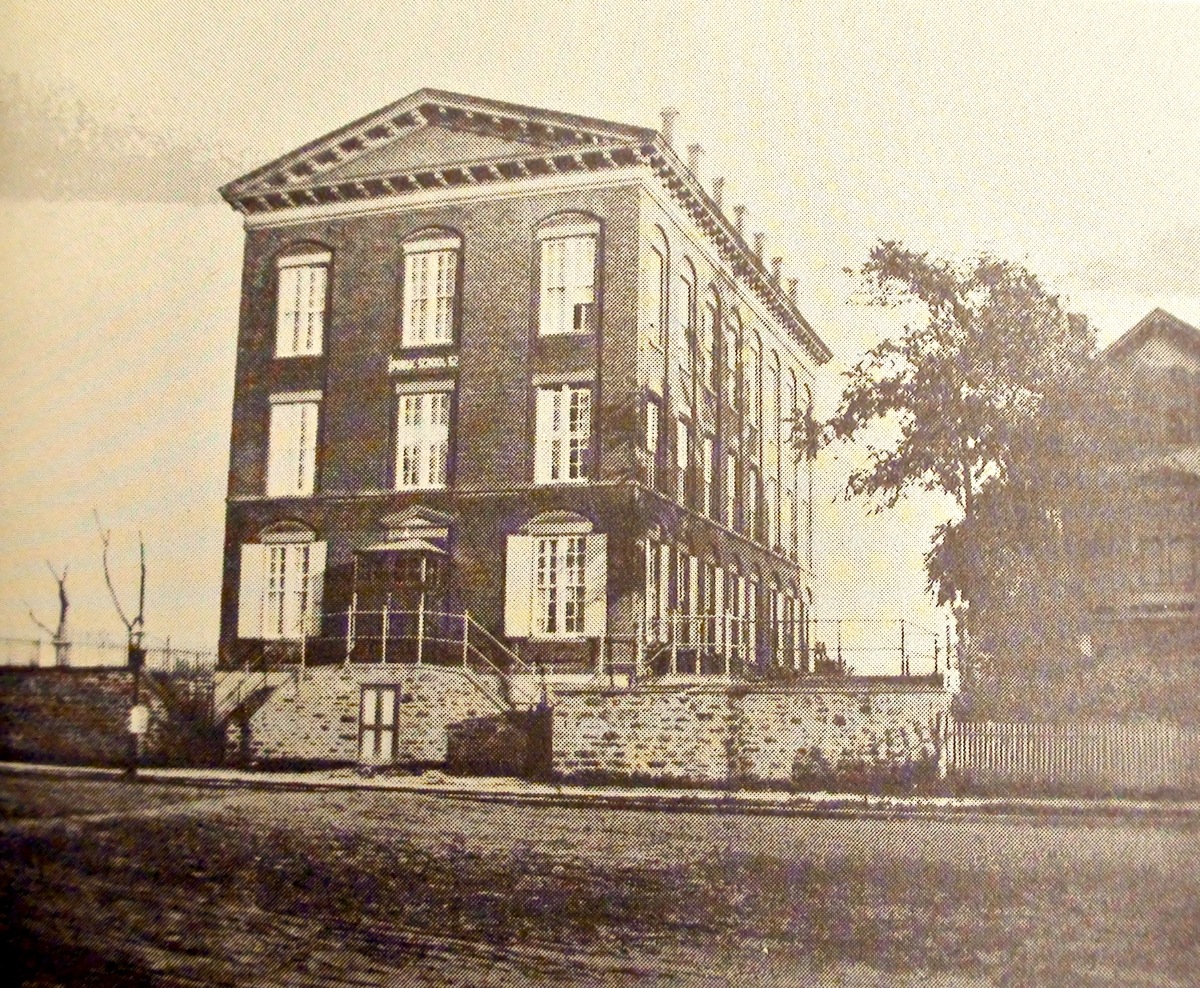

“Ward or Public School No. 52 was a landmark on the southeast corner of Broadway and Academy Street from 1858 to almost 1957. This picture dates from about 1902, or midway of that period. Note the gas lamp with a mailbox on the lamppost. At the right is the house where the caretaker lived.” -Source- William Tieck, Schools and School Days.

In 1858, the year Inwood’s first school was constructed , the area wasn’t even yet known by its current name. Locals, of whom there were few, all referred to the region on Manhattan’s northernmost tip as “Tubby Hook.” Folks downtown hardly even considered the backwater region as being part of their city.

So imagine the surprise when a monolithic, rectangular red-brick structure capped by fourteen chimneys rose from a cow pasture on what we now know as Academy Street and Broadway. Everyone, locals included, were puzzled as to the need for such a large and modern structure. There were barely enough children in the area to fill even the first floor. Besides, children in those lean times, like their parents, literally lived off the land, and were needed in the fields to care for the crops and herd cattle. Who really had time for school?

Public School 52 on Broadway and Academy in 1930. Note old and new schools sit side by side before demolition of old school in 1956.

According to the late Kingsbridge historian William Tieck, “the growth of the Tubby Hook school was so slow that during the first thirty or forty years of its existence only the lowest floor of the three story structure was used. Because School Commissioner James MacKean was one of the prime movers in the erection of the building, it was long known as “MacKean’s Folly”. The land itself was donated by Isaac Michael Dyckman, who retained an active interest in the school until his death in 1899.” (Schools and School Days in Riverdale, Kingsbridge and Spuyten Duyvil, 1971).

“Even as late as 1908, when Public School 52 celebrated its fiftieth anniversay, it was surrounded by the wide-open spaces shown in the remarkable vista above. The picture was taken in a northeasterly direction overlooking the junction of Riverside Drive with Broadway and Dyckman Street. To the right of the school is the mansion-like dwelling of the caretaker, Mr. O’Neill. Landmarks include the original Mount Washington Presbyterian Church; above its steeple, the now abandoned powerhouse at 216th Street; and, on the horizon, the two buildings of the Catholic Orphan Asylum and Webb’s Academy and Home for Shipbuilders. A string of subway cars is barely visible on the distant-and then new- elevated line running up Tenth Avenue. Note the trolley tracks and gas lamps.” Source: William Tieck, Schools and School Days.

More than a century before Tieck’s seminal work on the history of education in the Kingsbridge section of New York, a reporter from the New York Herald visited the old Ward School 52 as part of an annual examination of city schools.

According to the article, dated June 16, 1865, “The new and progressive schoolhouse at Tubby Hook is one of the most interesting monuments of that beautiful and romantic region. Yesterday the annual examination of the classes was made by Mr. S. S. Randall, the General Superintendent of Schools, with the assistance of Assistant Superintendent N. A. Calkins, H. Kiddle and William Jones. There were eight classes—five grammar and three primary—consisting of one hundred and fifty children in all. They were under the management of Mr. G. Miller, the principal, and his three pretty and intelligent lady assistants. Indeed, all the lady teachers of New York are pretty and intelligent—so much that, in this respect, they differ from the teachers of other cities. They seem to be appointed for their beauty and intellect. The examination was careful and searching, and embraced mathematics, astronomy, geology, history, grammar and a variety of other studies. All the classes acquitted themselves well, and the result of the examination was by no means discreditable to them.”

Ah the ladies…but we digress.

The sturdy old building stood for nearly a century, with civil war heroes and other famous men passing through its doors before it was demolished in 1956 to make room for an addition to the newly constructed J.H.S. 52.

What follows is a 1911 newspaper description of Inwood’s first public school during its prime:

The Sun

March 26, 1911

TUBBY HOOK’S OLD SCHOOL

ANTIQUATED STRUCTURE UPTOWN WHICH HAS A HISTORY.

Something About the District in Which It Stands—Many Well Known Men Went to School In Old 52—The Late John B. McDonald One of Them.

In the upper end of the city, on Manhattan Island, surrounded by up to date apartment houses, electric railroads underground, and in the near distance over-head trolley roads, the elevated part of the subway as well as the main line of the New York Central Railroad, stands an old fashioned brick schoolhouse where formerly a genuine excuse for absence from school was given by the parents of pupils as “the boys were needed to drive the cows to pasture.”

Up to about twenty-five years ago the place, 206th Street and Broadway, was known as Kingsbridge Road. Inwood: locally and unofficially it was also known as Tubby Hook; muddy in winter, dusty in summer and looked upon by a non-resident as not being part of the city of New York. The origin of the name Tubby Hook may be traced to a family named Tubb who lived in the neighborhood of a point of land just a short distance south of the Spuyten Duyvil. This locality was later known as Inwood on the Hudson, warranted by the extensive woods surrounding the Dyckman tract of land, and is known now as Dyckman street and Broadway, about a hundred feet south of where the old schoolhouse stands.

To get at the history of this old familiar landmark, which is part of our present local school system, it is necessary to inspect the records of the township of New Haarlem, of which Washington Heights forms a part. A few years after the town was established in 1658 by the last of the Dutch Governors, Peter Stuyvesant, the famous one legged soldier recognized the need of some one person to perform the duties of a schoolmaster for the poor children of the district; the population of Manhattan Island at this time, December 4, 1663, was about 2,000 souls. The Schepens, or Magistrates, held a lengthy meeting, and at its close “a capable man” was appointed; but the very limited means of the residents prevented them from contributing toward the schoolmaster’s salary.

The best they could do was to give two dozen schepels of grain each for his support. The absence of money made it obligatory on the part of the Magistrates, Daniel Tournier and Johannes Verveelea, also Jan Pieterson Slot, who could not write his own name, to petition the Director General and Council of New Netherland for a grant in aid of the appointment of Jan La Montegne, Jr., son of a physician, who was one of the first settlers of New Haarlem. At the time of his appointment the future schoolmaster, who was secretary of the Board of Magistrates and a parish clerk, resigned to take up his new duties at a salary of fifty guilders ($20) per annum, which was considered “the least possible salary.”

For seven years, or until 1670, Mr. La Montagne served in the capacity of schoolmaster, when he moved away. Hendrik Van der Vin succeeded him and fulfilled the same duties at a salary of eight times as much as that paid to Mr. La Montagne. The increase in the schoolmaster’s salary was evidentially too much for the residents, for when his salary was not forthcoming in 1678 it became necessary to make a house to house canvas for subscriptions, which netted 300 guilders, an matters were squared with New Haarlem’s second schoolmaster, at least for the time being. This subscription, together with the rent of the town meadows, was devoted to the salary and support of Mr. Van der Vin, who agreed after some persuasion to accept it for the first year, after which his full salary was assessed upon the residents. The town also voted to rebuild his residence. Nevertheless he lived in poor circumstances and finally fell into debt, the town being compelled in 1682 to pay a bill of $6 for Van der Vin’s pens, ink, paper and writing material.

Reginald Pelham Bolton, a civil engineer, and a well known resident of Washington Heights, whose ancestors owned considerable property in the neighborhood of Bolton road, just west of Broadway and near the old schoolhouse, has in his possession a large quantity of old time official records, one of which bears testimony that Van der Vin was a gentleman well acquainted with Latin and Spanish, remarkable for his accuracy, methodical in his habits and very precise in his duties as a clerk.”

He was succeeded by John Tiebout, who resigned after some years and gave way to Guiliaem Bertholf, who served for one year. Tiebout returned and served until 1690, when he and his family of twelve children moved to Bushwick. Tiebout was succeeded by a young man, a recent arrival from Vlissingen by the name of Adrien Verrautl, and “judging from his penmanship, a scholar,” who filled the place until 1708 when he became voorleser at Bergen, N.J., being recommended by the people of New Haarlem.

Religious discussion of an acrimonious nature left the town without a schoolmaster for about fourteen years, or until 1722 when John Martin Van Harlingen arrived from Holland, who held the position until 1741, although for a long time after this the New Haarlem church people made no appointment. The war of the Revolution did away with education; something more important at this period, many sought protection inside the American lines, returning after evacuation to find their homes ruined.

Chapter 189, Laws of 1801 enacted by the Legislature then holding its twenty-fourth session at Kingston, N.Y., provided that a sum of be raised by a tax for the further support of government, such moneys to be invested in real securities and the interest thereof to be expended for the instruction of poor children in the most useful branches of common education. A town meeting was held in this year and arrangements were made to lease a portion of the common lands to establish an academy for the education of the children of the township, these lands were then situated in the old Ninth ward of the city of New York and caused considerable controversy with the city. A legislative act caused the land to be sold, the proceeds to be placed in the hands of various trustees, who paid $3,500 to the trustees of the “Hamilton School.” The exact date of the establishment of it is in doubt, but references show it to be prior to 1820. Valentine’s Manual shows the Hamilton free school to be located at 181st street and Fort Washington avenue, the teacher then (1852) being Hosea B. Perkins, who died in 1903, the trustees being Isaac Dyckman, Tunis Ryer and John P. Dodge. This school was the predecessor of the present school system on Washington Heights.

In 1858, when the population of Manhattan Island was about 750,000, the Tubby Hook school—now Public School 52—was formally opened, the land upon which it stands being given to the city by the late Isaac Dyckman, on condition that a school be erected thereon. Until recent years only the first floor was used.

In 1903 a change was made in the building, which measured 40 by 70 feet, with classrooms about 16 square feet, the census of the old red school being less than 150, an addition of twenty-five square feet was added, the class rooms enlarged, the top floor occupied, giving more room, making the census of the school at the present time about 300, including about two dozen in the kindergarten. At the same time that the addition was made the old familiar brick walls were given a coat of paint and the “old red school” became a rich cream in color. It is only within the last few years that the old time stoves were replaced by steam heat.

It is questionable if any school in greater New York can show a list of well known graduates that are more respected in the community, among the alumni being the Rev. William J. Cummings and two brothers, John and Frederick; Lieut. Samuel K Allen, a graduate of West Point; his brother, Ethan Allen; J. Crawford McCreery, a partner of the dry goods firm; Samuel Isham, the artist and author; also his brothers, William and Charles; Dr. Norton Denslow and William Wallace Denslow, the well known illustrator and cartoonist; Elijah Cutts, late Senator from Minnesota; Joseph Keppler, artist and editor of Puck; Counsellor William Flitner and brothers, Walter and Charles; and William S. Hartt, director of the Tropical Fruit Growers Association. The old school also furnished some civil war heroes, such as Col. Charles N. Swift and Thomas C. Wright, both of whom rose from the ranks during the war; Col. Cornelius Schermerhorn, John Whalen, first Corporation Counsel of Greater New York and at present the president of Bank of Washington Heights; Blake Wales and his brother Alexander, Corporation Counsel of Binghamton in 1908; Robert Veitch and his son Charles of Dyckman Street; Theodore and Benjamin Barringer, both physicians, Former Alderman John J. McDonald, Andrew Thompson, one of the active members of the Stock Exchange; his brother William, and last but not least John B. McDonald, “the man who dug the subway,” and who died a week ago.”

-