Today northern Manhattan is home to thousands of gypsy cabs, but step back a century in time and you would find a sleepy little farming community inhabited by, among others, real life European gypsies.

Today northern Manhattan is home to thousands of gypsy cabs, but step back a century in time and you would find a sleepy little farming community inhabited by, among others, real life European gypsies.

As early as 1887, according to a New York Times article, Mr. J. Hood Wright allowed a full blown Romany encampment to set up shop on his property on Broadway and 173rd Street as part of a charity event to raise money for Manhattan Hospital.

And raise money they did. New Yorkers of the day seemed fascinated by gypsy culture and lined up at various booths to buy colorful clothing and trinkets or sample exotic food and fruits like crushed cantaloupes, pickled olives and fried shrimp.

According to the Times article, a team of female archers would allow “you for 15 cents to shoot a target with a bow and arrow. If you hit the bull’s eye you get an elegantly dressed cigar. If not you get another chance at paying 15 cents.”

According to the Times article, a team of female archers would allow “you for 15 cents to shoot a target with a bow and arrow. If you hit the bull’s eye you get an elegantly dressed cigar. If not you get another chance at paying 15 cents.”

And of course, there were the fortune tellers.

“The star of the occasion, however, is the Soothsayer. She is dressed in a wonderful robe of pink satin, which conceals everything but two penetrating brown eyes. She has a tent all to herself, and as you recline luxuriously on some Turkish cushions she takes your palm in hers and tells your fortune. She is a very good fortune teller. After she has won your interest and confidence by telling you a lot of things about yourself that you are surprised to find her in possession of, she paints your future brilliantly, paints it in rose color so to speak.”

She is a very good fortune teller. After she has won your interest and confidence by telling you a lot of things about yourself that you are surprised to find her in possession of, she paints your future brilliantly, paints it in rose color so to speak.”

A decade later, the Kingsbridge area had become so accustomed the gypsies living among them that in September of 1895 the Reverend Benjamin Burch, the rector of Saint Stephen’s Protestant Episcopal Church said a funeral mass for a young “gypsy Princess” named Little Patience Penfold.

According to the New York Times, “It was an unusual sight, the white vestments of the clergyman in the midst of the quaint gypsy camp. The body lay in a tiny white casket, in the little tent where it had been since death. On the coffin were two wreaths and a large cluster of daisies and goldenrod gathered from the fields nearby. A group of curious spectators stood near, and when the prayers were said all knelt, and many joined in the responses.”

Despite this outpouring of acceptance, the freewheeling days of setting up camp on the farms and pastures of this turn of the century hinterland were drawing to a close.

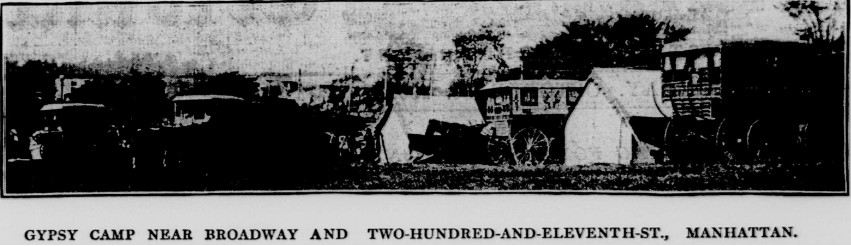

What follows is an inside look at one of the last, and possibly largest gypsy encampments in all of Manhattan. Located across Broadway from the present site of Isham Park, this incredible description comes from a 1904 edition of the now defunct New York Tribune.

New York Tribune Illustrated

October 30, 1904

“A real gypsy camp in the heart of the second city in the world is a picturesque sight just now on the meadows between Broadway, Harlem River and Two-hundred-and-eleventh and Two-hundred-and-twelfth Streets, which would probably surprise any one not familiar with the areas still remaining in their natural condition in upper Manhattan Island.

“A real gypsy camp in the heart of the second city in the world is a picturesque sight just now on the meadows between Broadway, Harlem River and Two-hundred-and-eleventh and Two-hundred-and-twelfth Streets, which would probably surprise any one not familiar with the areas still remaining in their natural condition in upper Manhattan Island.

The camp consists of a dozen house wagons of various types, as many tents, a couple of dozen horses tethered on the sloping meadow or grazing in the marsh, numerous dogs of indescribable breeds, and fifty or more gypsies of both sexes, ranging in age from infants in arms—or, more strictly speaking, infants on the ground—to veterans of threescore years and ten.

The men and older women are as swarthy as Arabs, but the middle aged women and children are fair, barring freckles. One or two of the families have been there for a couple of months, and are sending their children to the New York public schools. The others have just arrived from Danbury, where they have been attending the Danbury fair. The other day there was a great flurry in the camp when the old gypsy king and queen joined the colony, and were received with honors due to their exalted positions.

These gypsies are from Devonshire, England, and arrived in America two or three months ago with their equipages. They are an intelligent company, speak with a decided English accent, and are most civil in their address, adding “sir” to almost every sentence. They dress in bright colors, and their clothing, displayed on the grass and bushes to dry on “wash day,” imparts a kaleidoscopic aspect to the landscape. They make a living by trading horses and telling fortunes by palmistry, and some of them are believed to possess no inconsiderable means.

These gypsies are from Devonshire, England, and arrived in America two or three months ago with their equipages. They are an intelligent company, speak with a decided English accent, and are most civil in their address, adding “sir” to almost every sentence. They dress in bright colors, and their clothing, displayed on the grass and bushes to dry on “wash day,” imparts a kaleidoscopic aspect to the landscape. They make a living by trading horses and telling fortunes by palmistry, and some of them are believed to possess no inconsiderable means.

The gypsy boys are interesting little chaps—alert, bright, and as inquisitive as a corkscrew. They wear curious jackets, the fronts of which are made of plaid stuff and the sleeves and backs of buckskin, making them look as if they were in their waistcoats. They have their pets with them. One has a little Shetland pony, which is tethered to a stake in the middle of the camp and nibbles at grass contentedly. Another has a rabbit, which hops in and out among the heaps of firewood that have been gathered for their campfires. Another has a canary bird hanging in a cage at the front door of the house wagon.

The gypsy boys are interesting little chaps—alert, bright, and as inquisitive as a corkscrew. They wear curious jackets, the fronts of which are made of plaid stuff and the sleeves and backs of buckskin, making them look as if they were in their waistcoats. They have their pets with them. One has a little Shetland pony, which is tethered to a stake in the middle of the camp and nibbles at grass contentedly. Another has a rabbit, which hops in and out among the heaps of firewood that have been gathered for their campfires. Another has a canary bird hanging in a cage at the front door of the house wagon.

These house wagons, which are sometimes used by English people who are not gypsies for summer outings, are different from anything made in this country. They are wholly enclosed like a stage, but wider at the top than at the bottom, and open in front instead of behind. At the rear is a track for transportation of the canvas and other impedimenta. On the front of the vehicle, on each side of the front door, is a tier of little shelves or racks—a convenient resting place for the canary bird cage and other light articles in fair weather. Within, on each side, is a long seat. The side windows are neatly curtained, and above them, and on the further end, are pictures and other household ornaments. The interior has an inviting air of snug comfort, tempting to one fond of outdoor life.

These house wagons, which are sometimes used by English people who are not gypsies for summer outings, are different from anything made in this country. They are wholly enclosed like a stage, but wider at the top than at the bottom, and open in front instead of behind. At the rear is a track for transportation of the canvas and other impedimenta. On the front of the vehicle, on each side of the front door, is a tier of little shelves or racks—a convenient resting place for the canary bird cage and other light articles in fair weather. Within, on each side, is a long seat. The side windows are neatly curtained, and above them, and on the further end, are pictures and other household ornaments. The interior has an inviting air of snug comfort, tempting to one fond of outdoor life.

One or two families have a camp stove, but most of them cook in true nomadic style, slinging their kettles over the campfire from tripods. They have a great admiration for America—having seen Danbury, Conn., some parts of New Jersey and New York City— and they are free to admit that New York is superior to Danbury. They will probably remain here for some time.”

One or two families have a camp stove, but most of them cook in true nomadic style, slinging their kettles over the campfire from tripods. They have a great admiration for America—having seen Danbury, Conn., some parts of New Jersey and New York City— and they are free to admit that New York is superior to Danbury. They will probably remain here for some time.”

But by 1904 such camps would become all but impossible. That year the elevated IRT (today’s one train) arrived in Inwood. With it came aggressive real estate speculation and development. The flowing pastures needed for a proper encampment were either developed or spoken for.

The gypsies like so many other cultures before and since, were pushed out of the neighborhood in the name of progress.