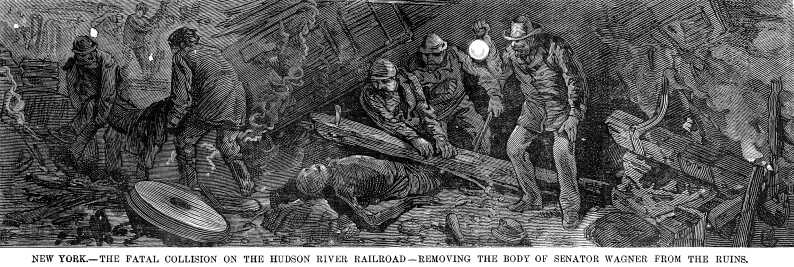

“The body of Senator Wagner was a spectacle never to be forgotten. The head was burnt and charred beyond the possibility of recognition, the legs were burnt off and the trunk bruised and disfigured…Later in the night he was identified by his gold watch, bearing the initials “W.W” his diary and several newspaper slips giving the election returns of his Senatorial district.”—The New York Truth, January 15, 1882.

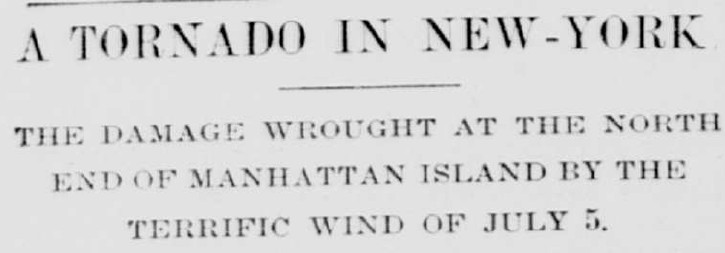

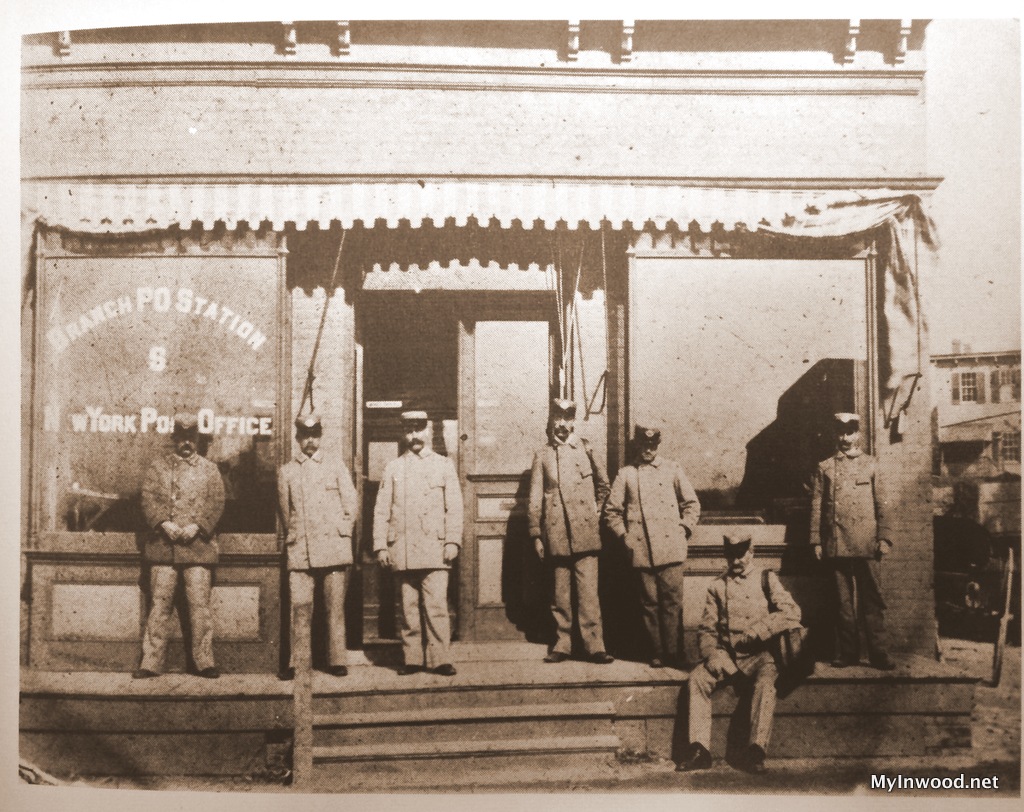

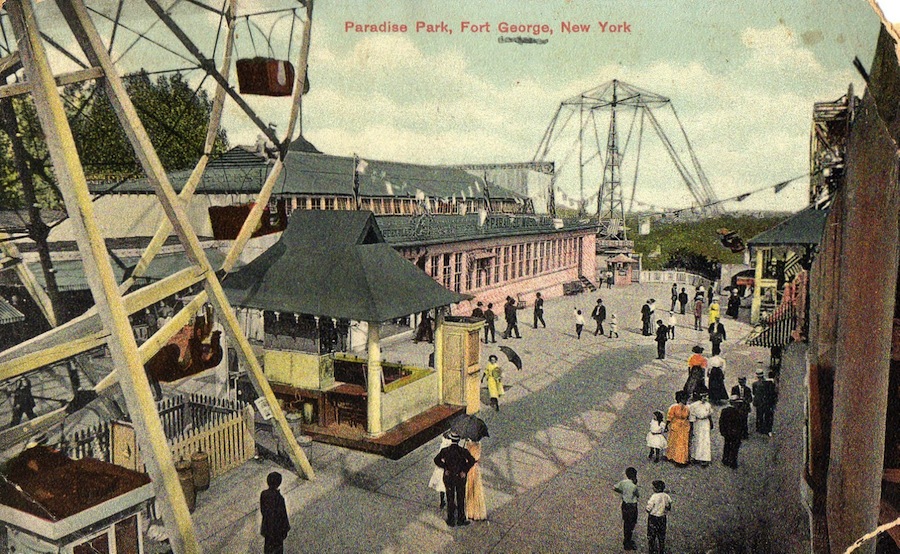

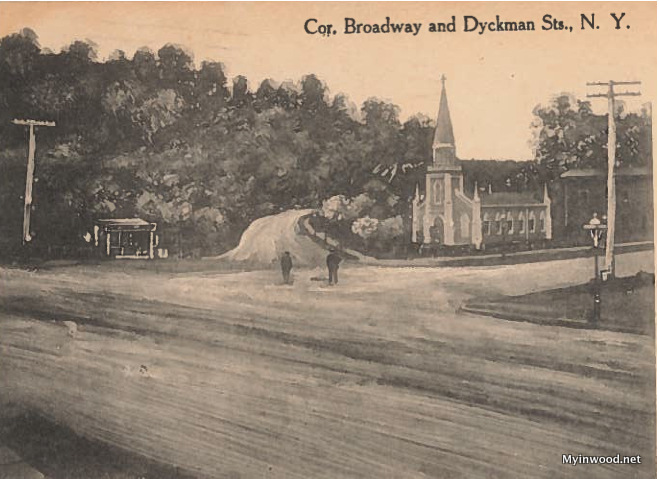

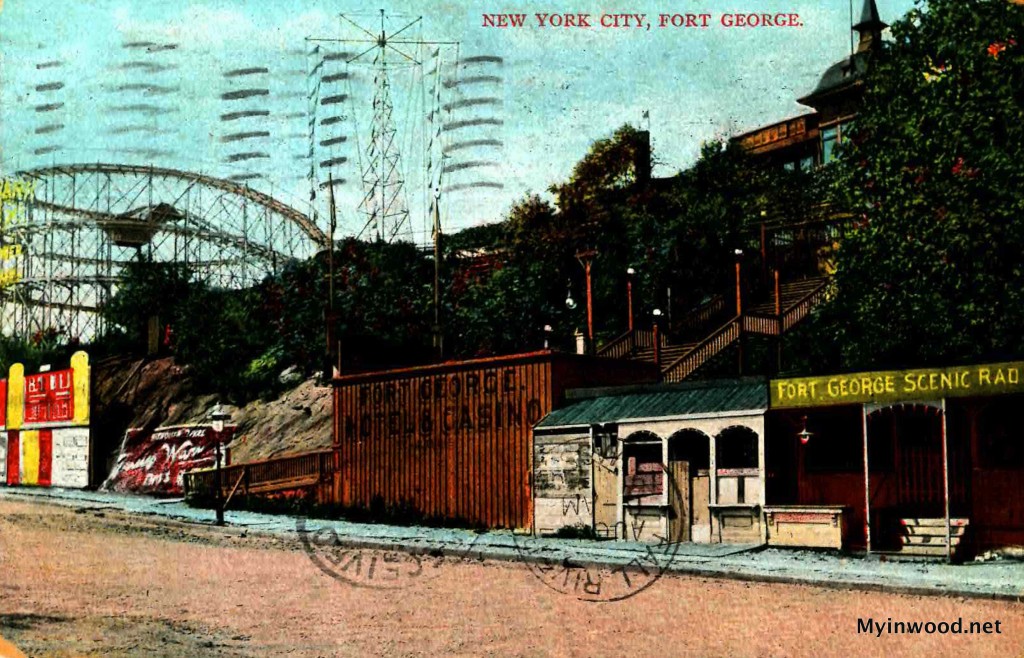

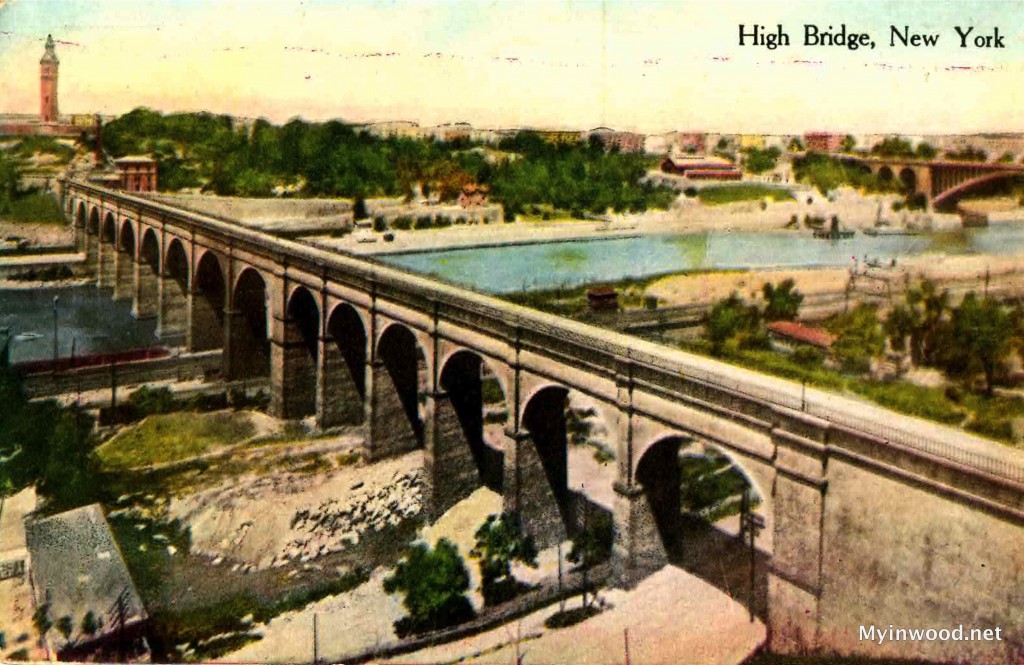

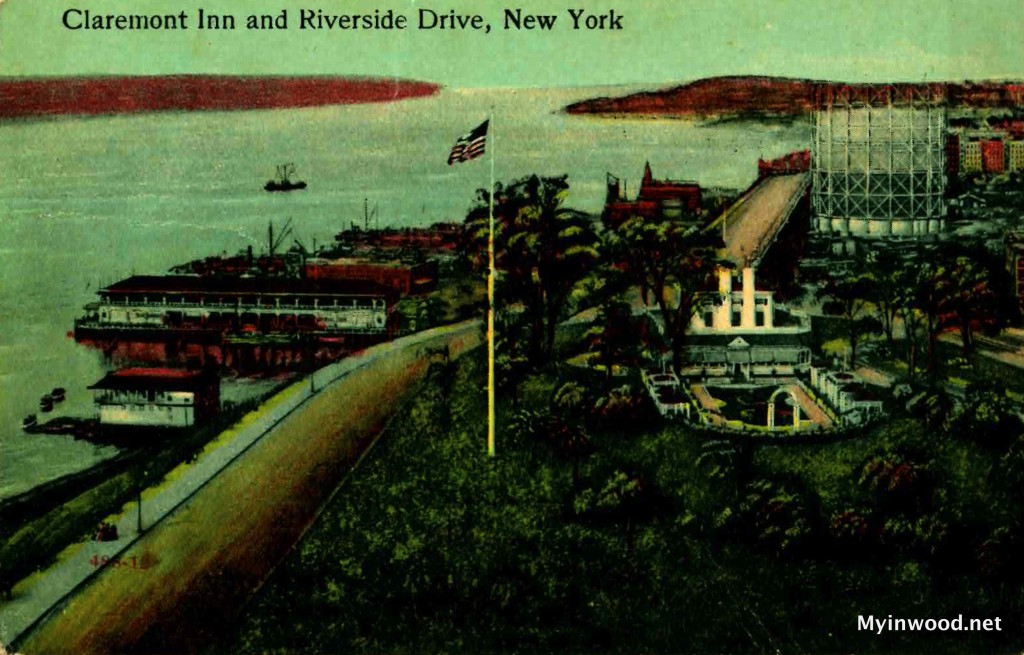

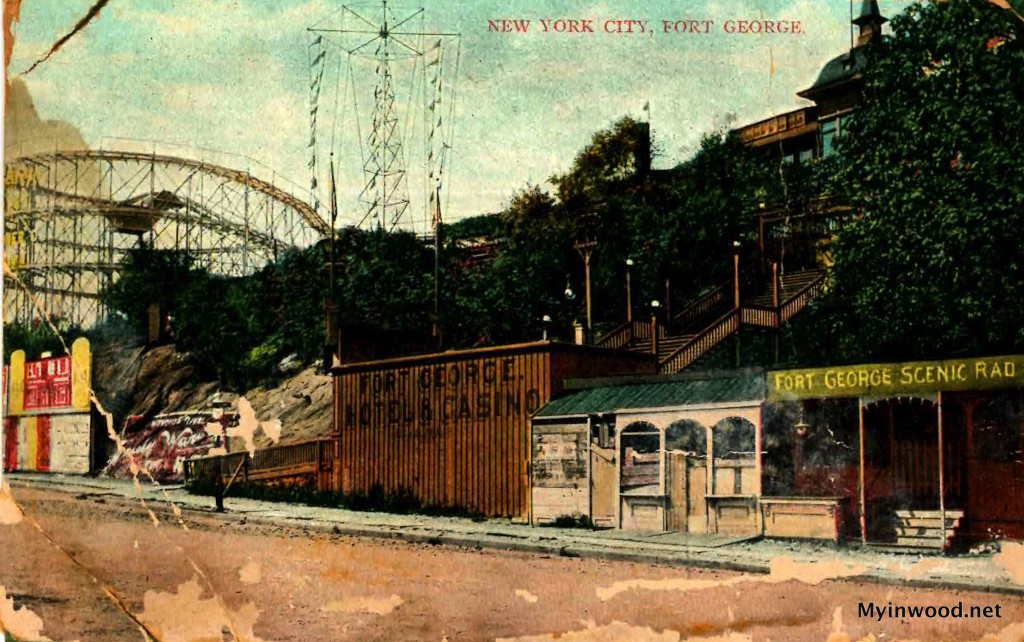

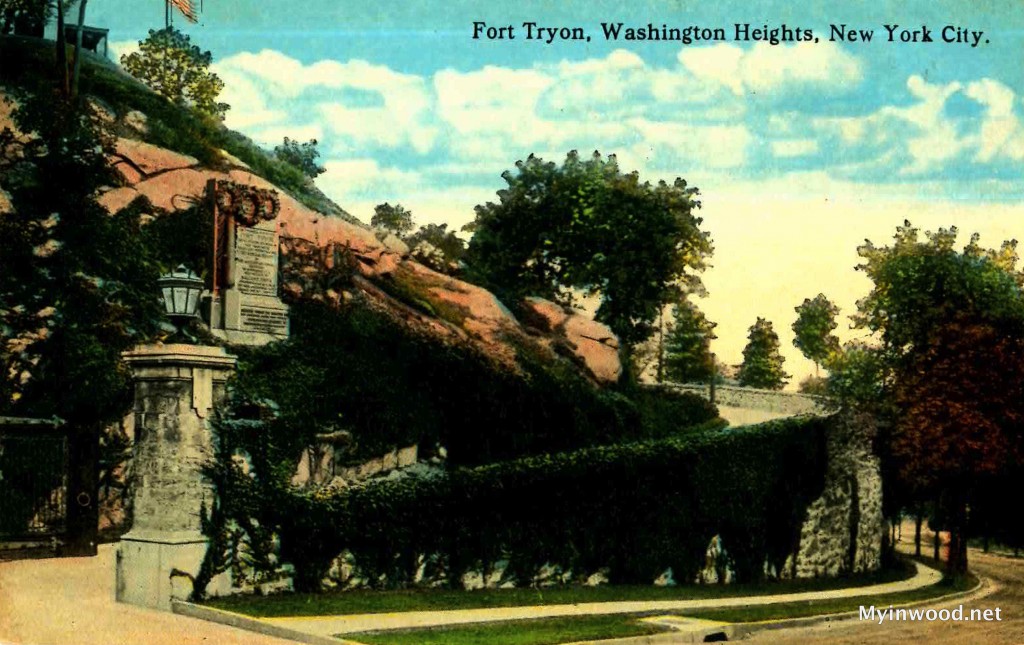

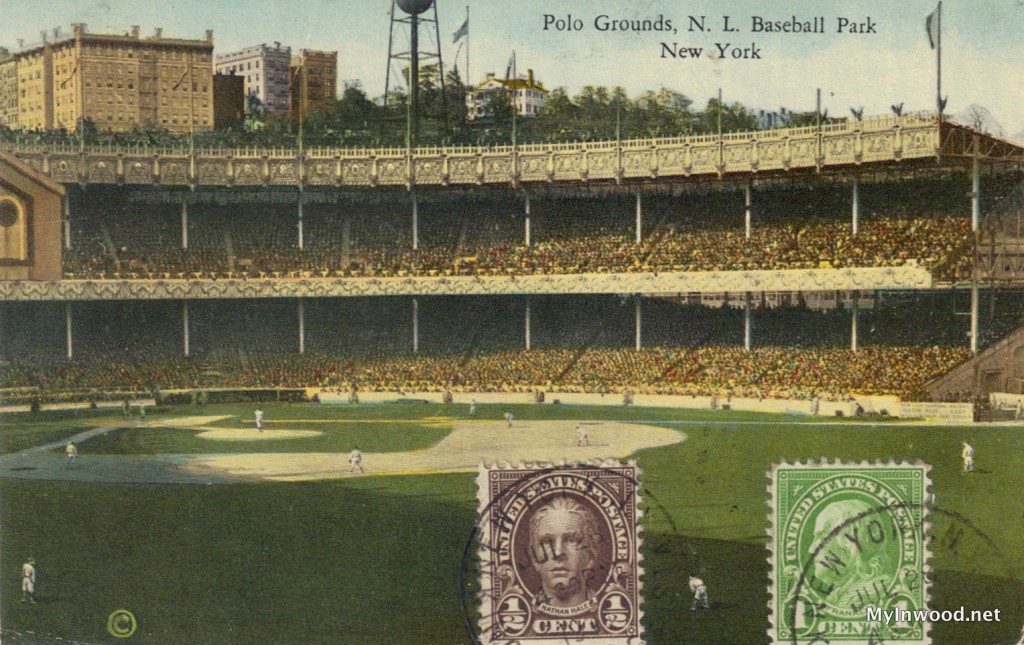

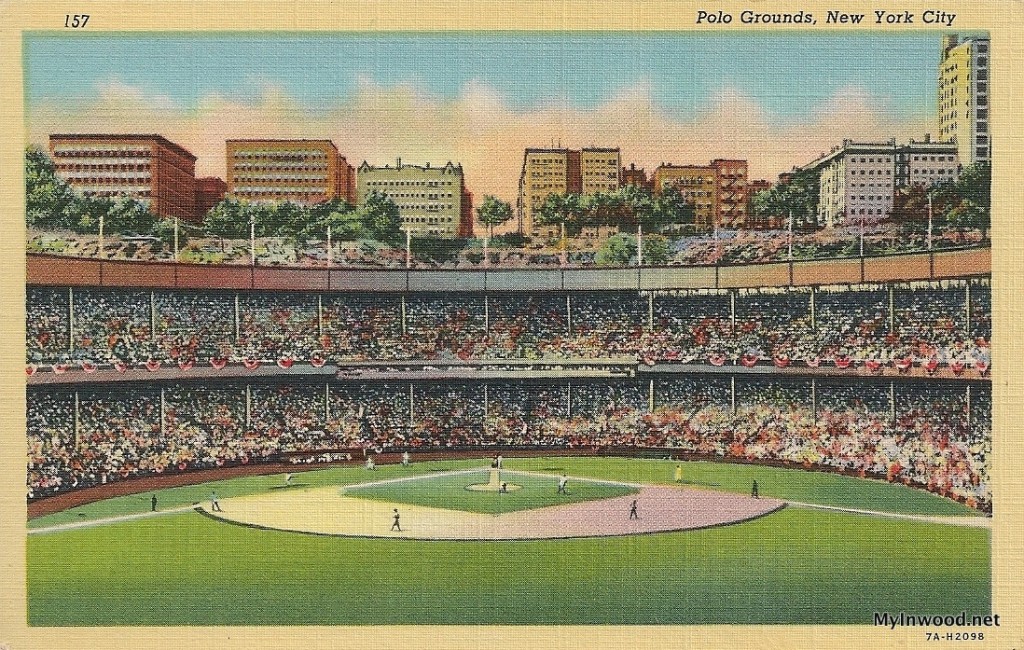

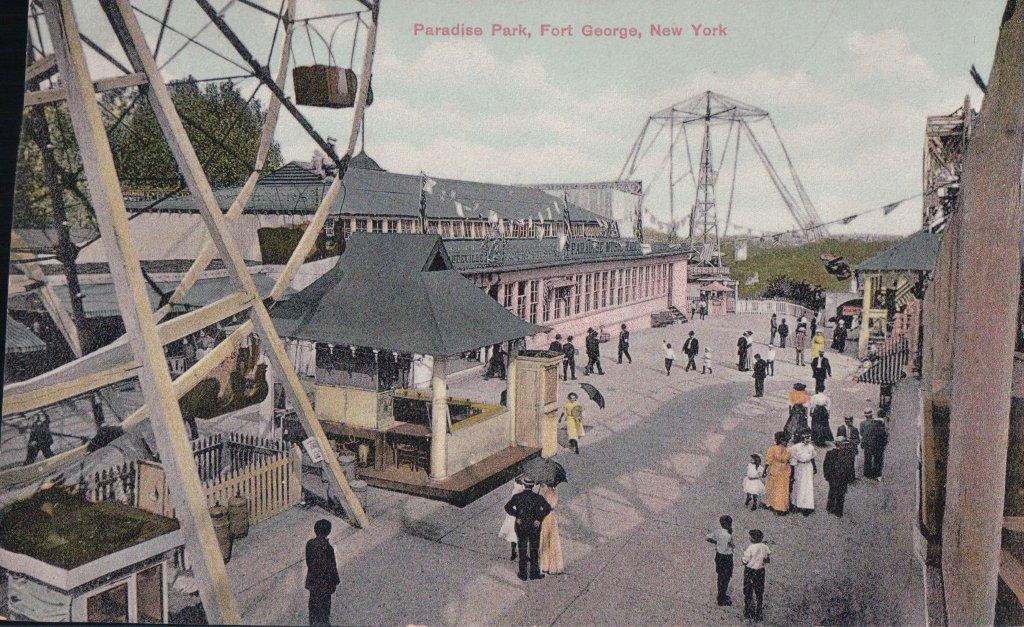

![Railroad Stories, 1935.]()

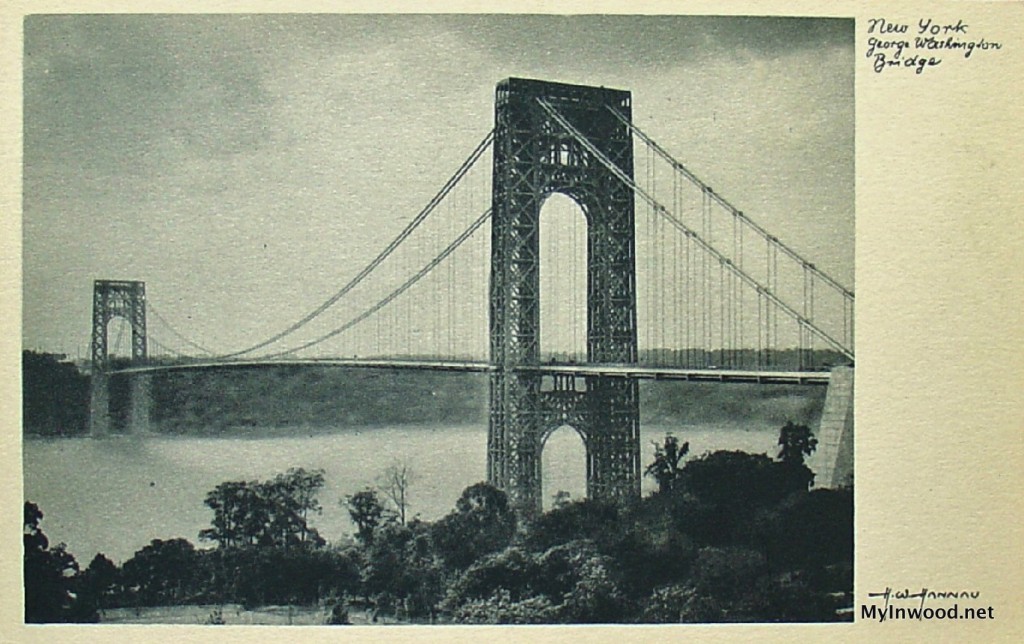

Railroad Stories, 1935.

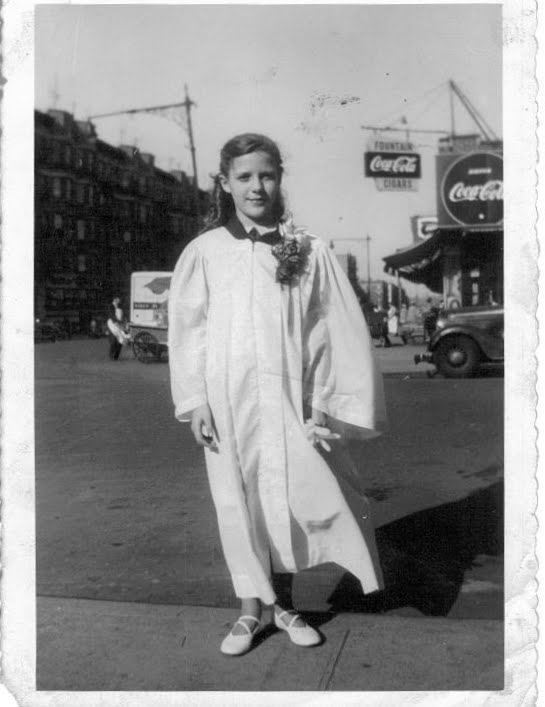

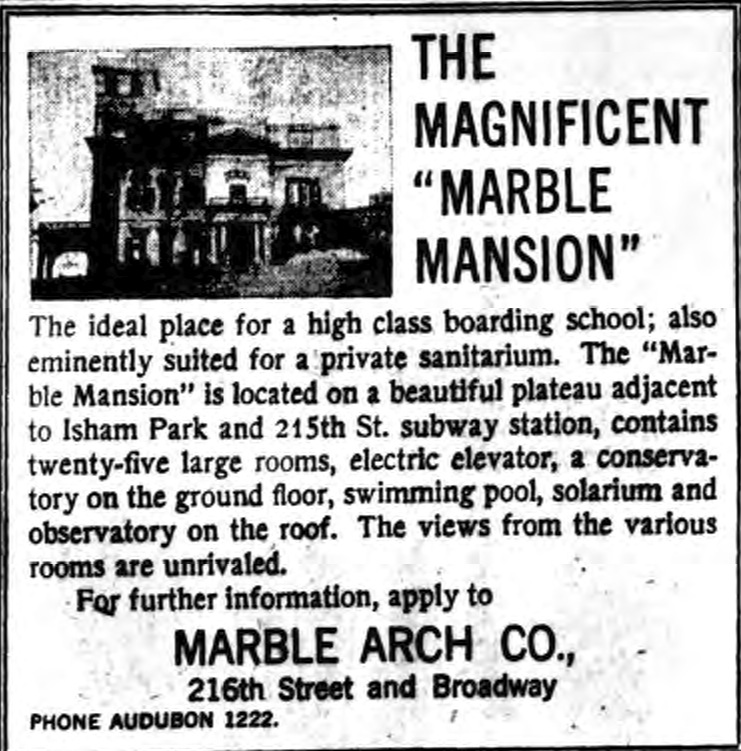

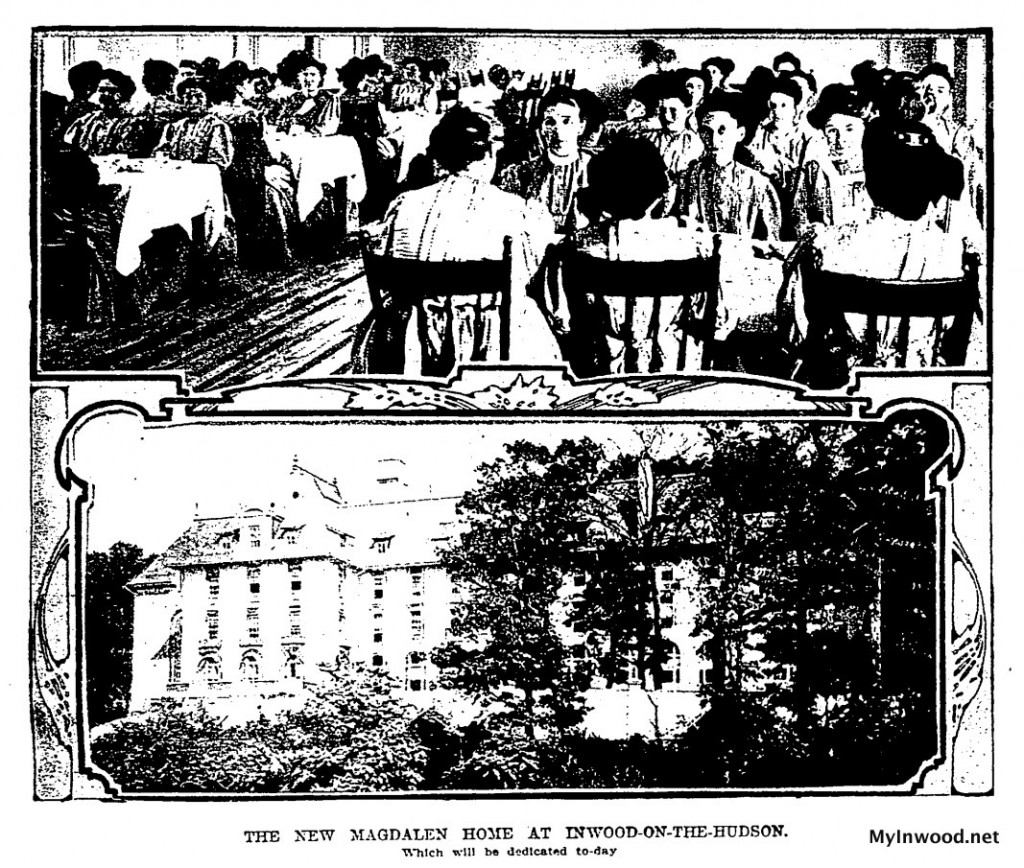

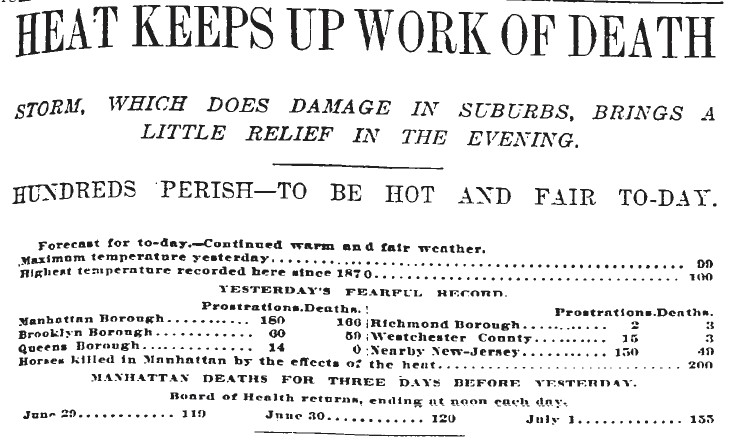

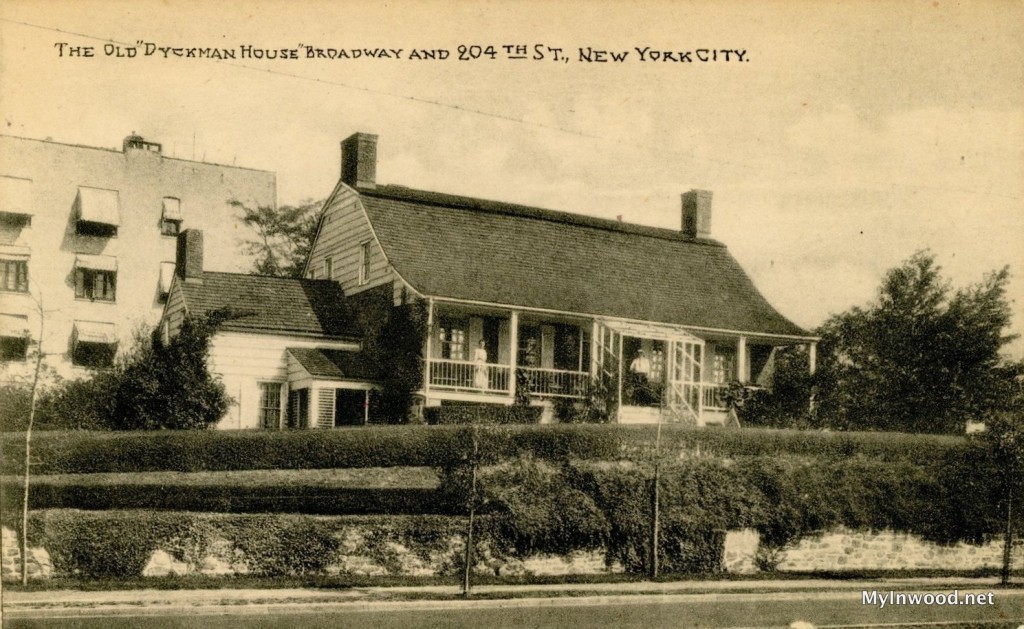

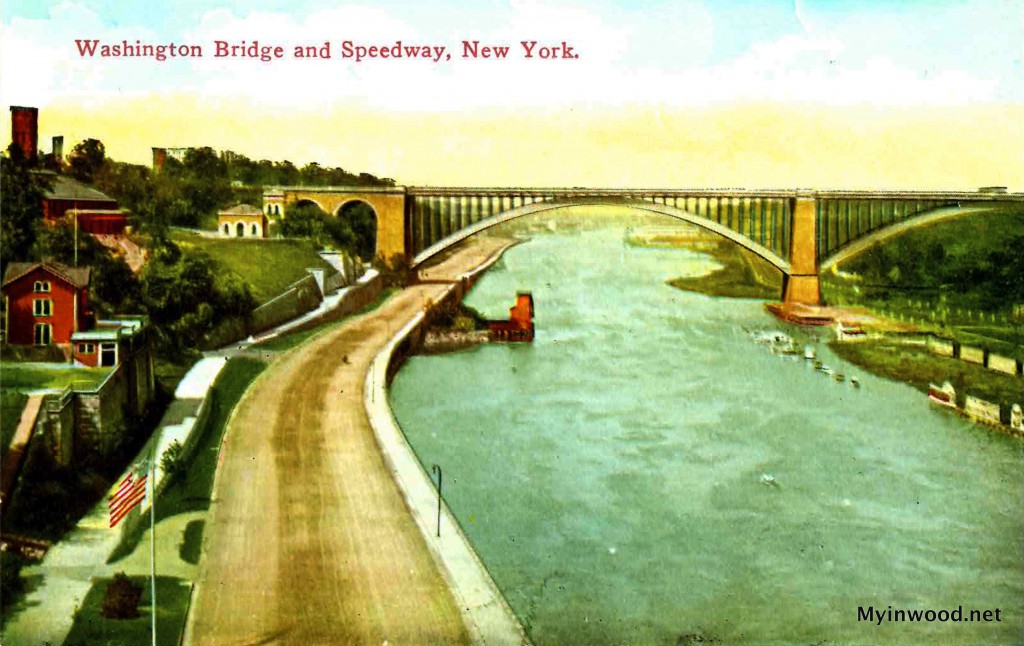

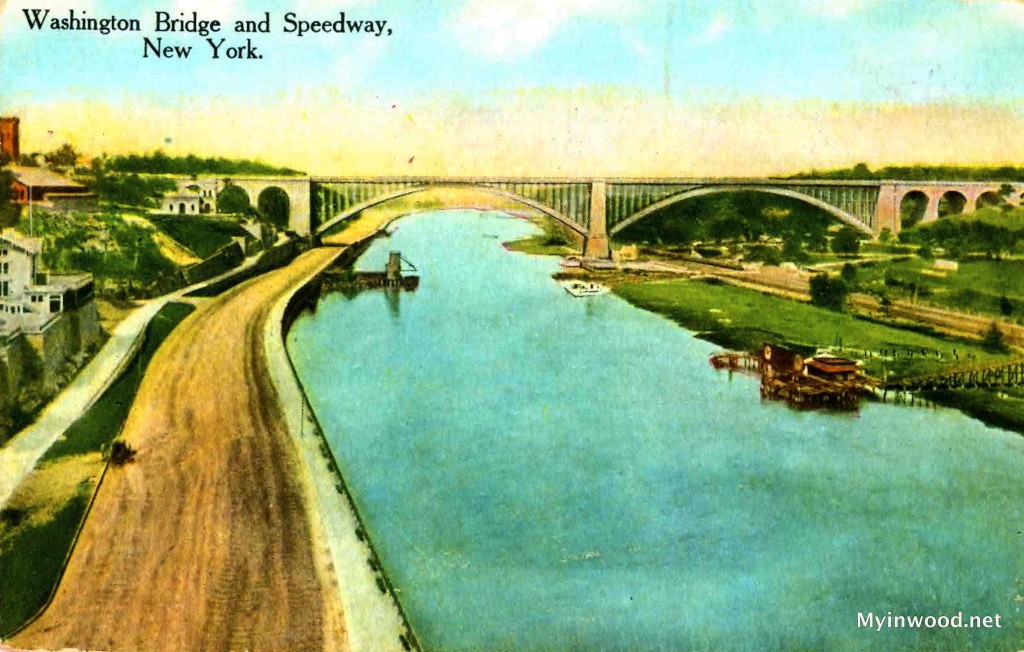

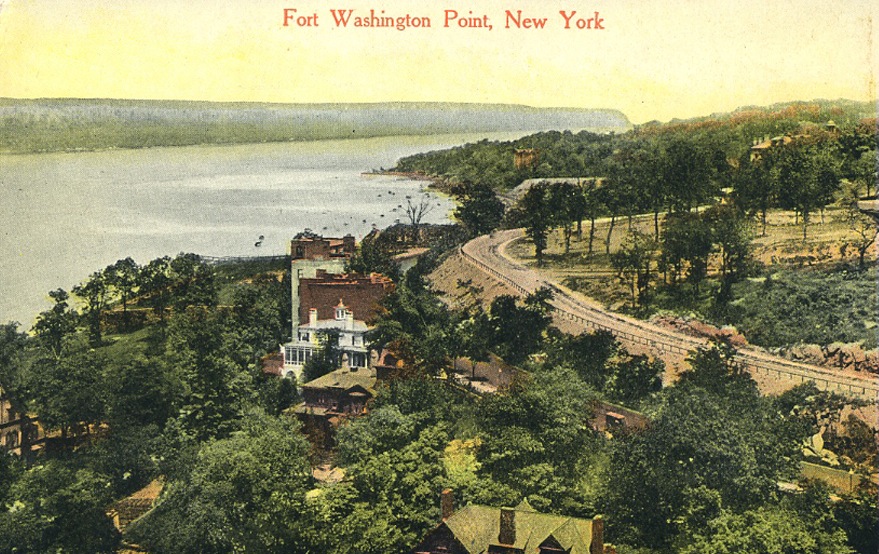

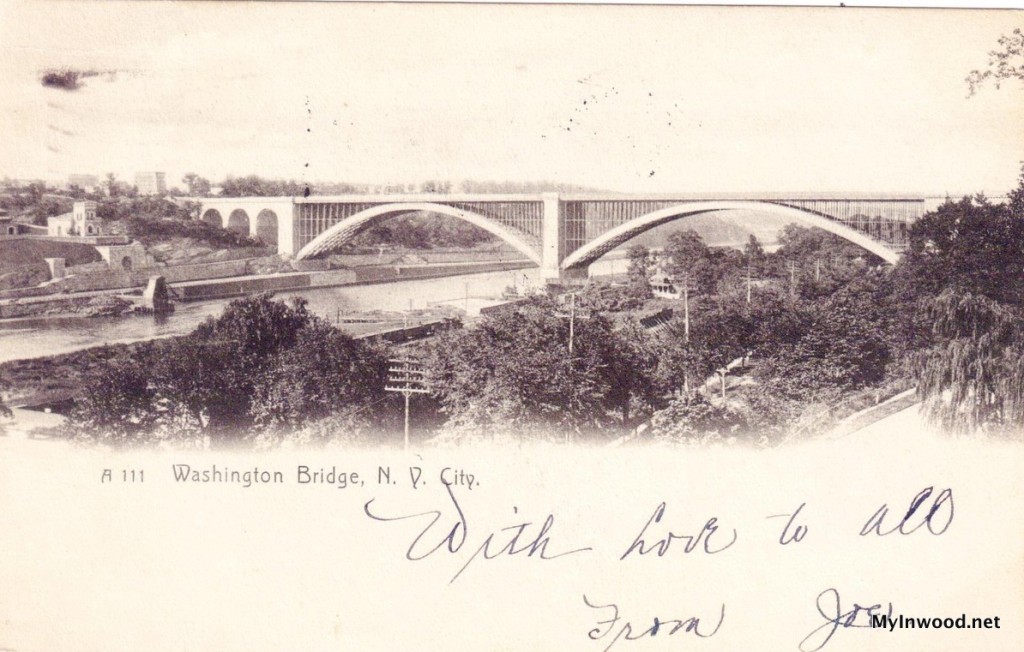

On the evening of January 13, 1882 the Western Express from Chicago pulled into Albany twenty-three minutes late. The State Legislature had just let out for the weekend and the Tammany Hall politicians were eager to get back to New York City for the weekend.

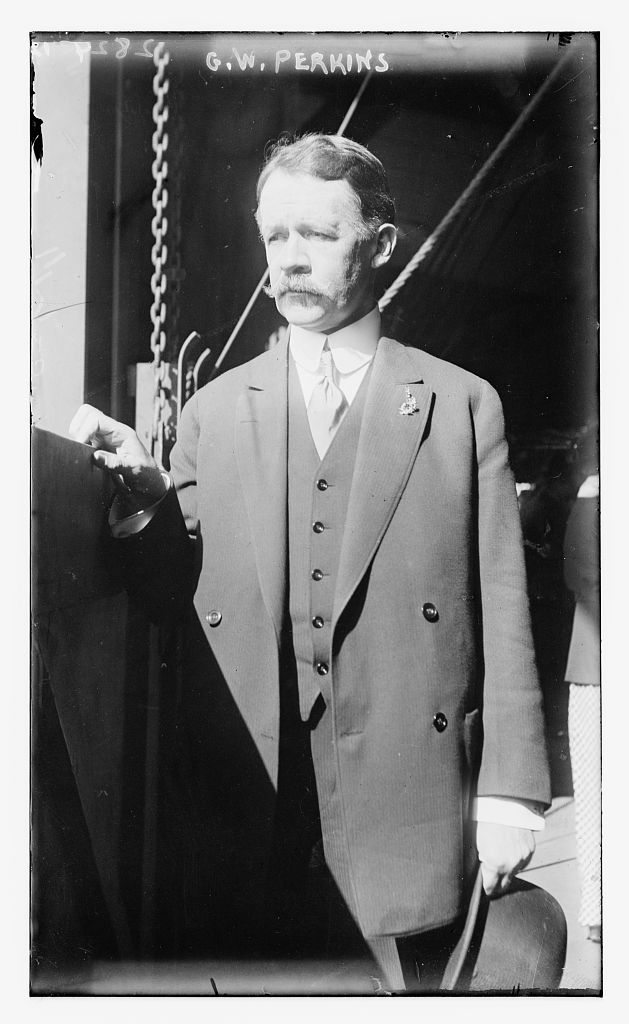

![Webster Wagner]() Demand for seats was so great that the railroad took on an extra fifteen cars accommodate the 500 new passengers. The fifteen new hitches included eight gleaming palace cars designed by burgeoning railroad tycoon and State Senator Webster Wagner. In addition, two extra engines were added to accommodate the additional weight as well as make up for lost time.

Demand for seats was so great that the railroad took on an extra fifteen cars accommodate the 500 new passengers. The fifteen new hitches included eight gleaming palace cars designed by burgeoning railroad tycoon and State Senator Webster Wagner. In addition, two extra engines were added to accommodate the additional weight as well as make up for lost time.

Wagner, on-board the train, proudly described his parlors of luxury, or “rolling stock,” as he was fond of saying, to reporters and colleagues as champagne poured freely.

The trip was a jolly one. Snow settled softly alongside the tracks as the train barreled ever southward.

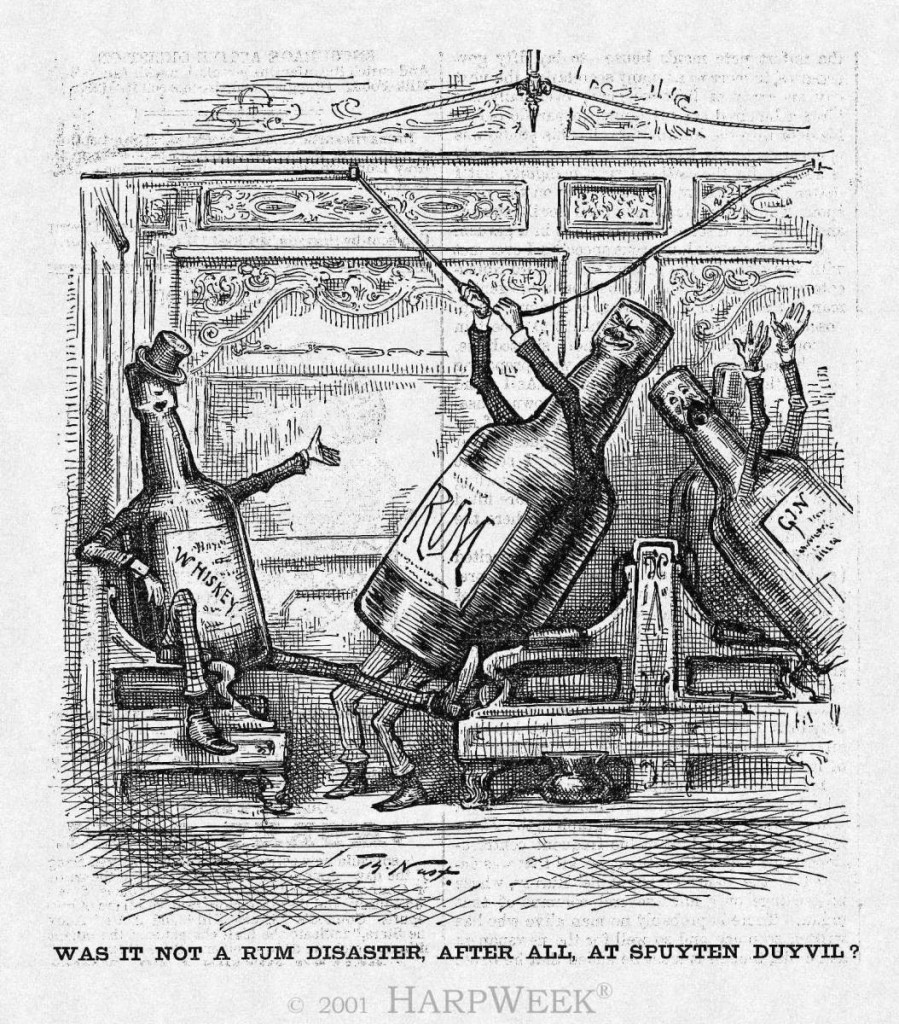

As the ride progressed the night turned into a booze fueled bacchanalia—the drunken passengers unaware of the impending disaster that lay around the bend.

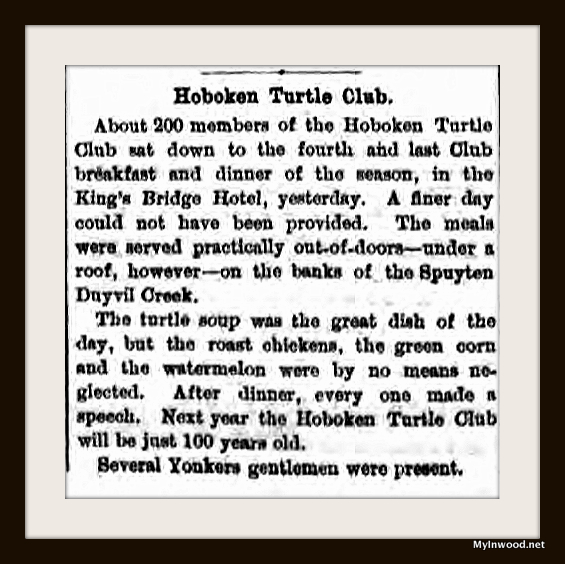

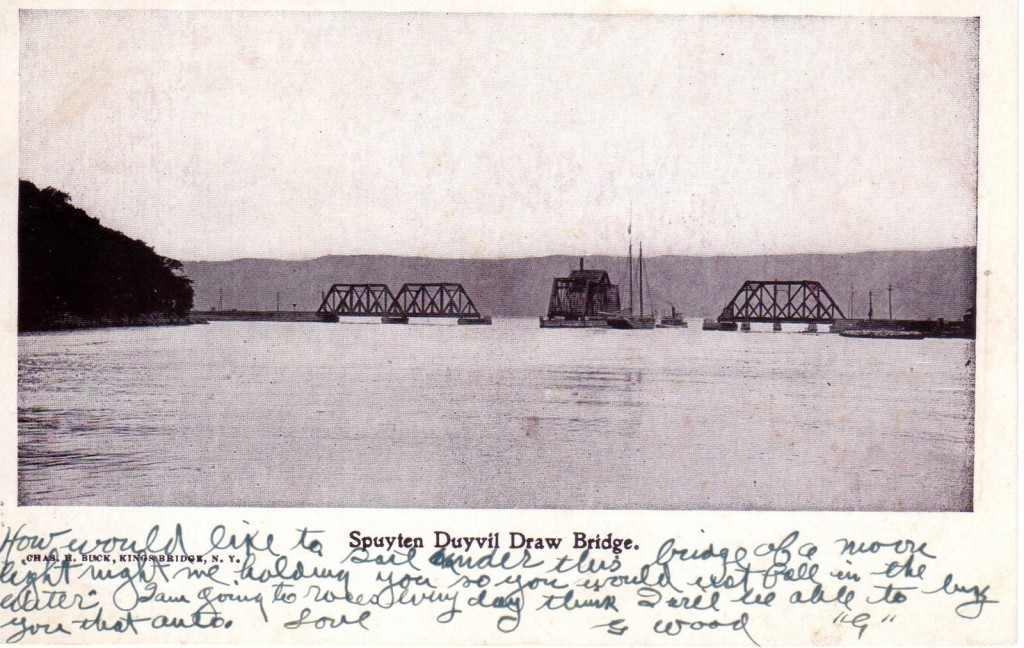

Just after the Chicago express passed the hairpin turn where the Hudson River meets the Spuyten Duyvil, the locomotive came to an abrupt stop. Perhaps a drunken reveler had pulled the air brake as a gag?

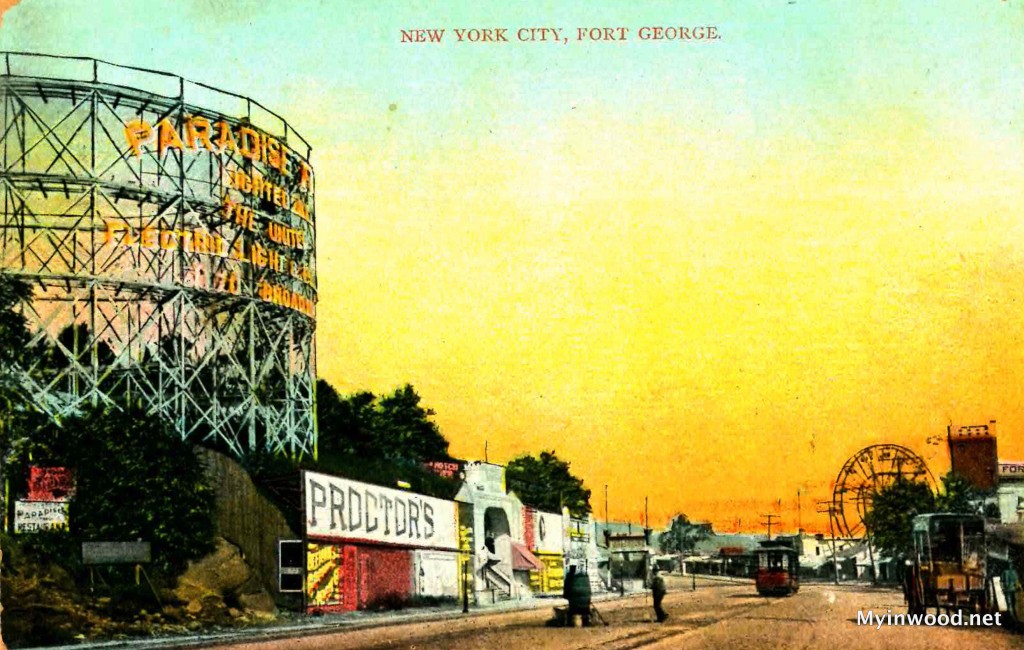

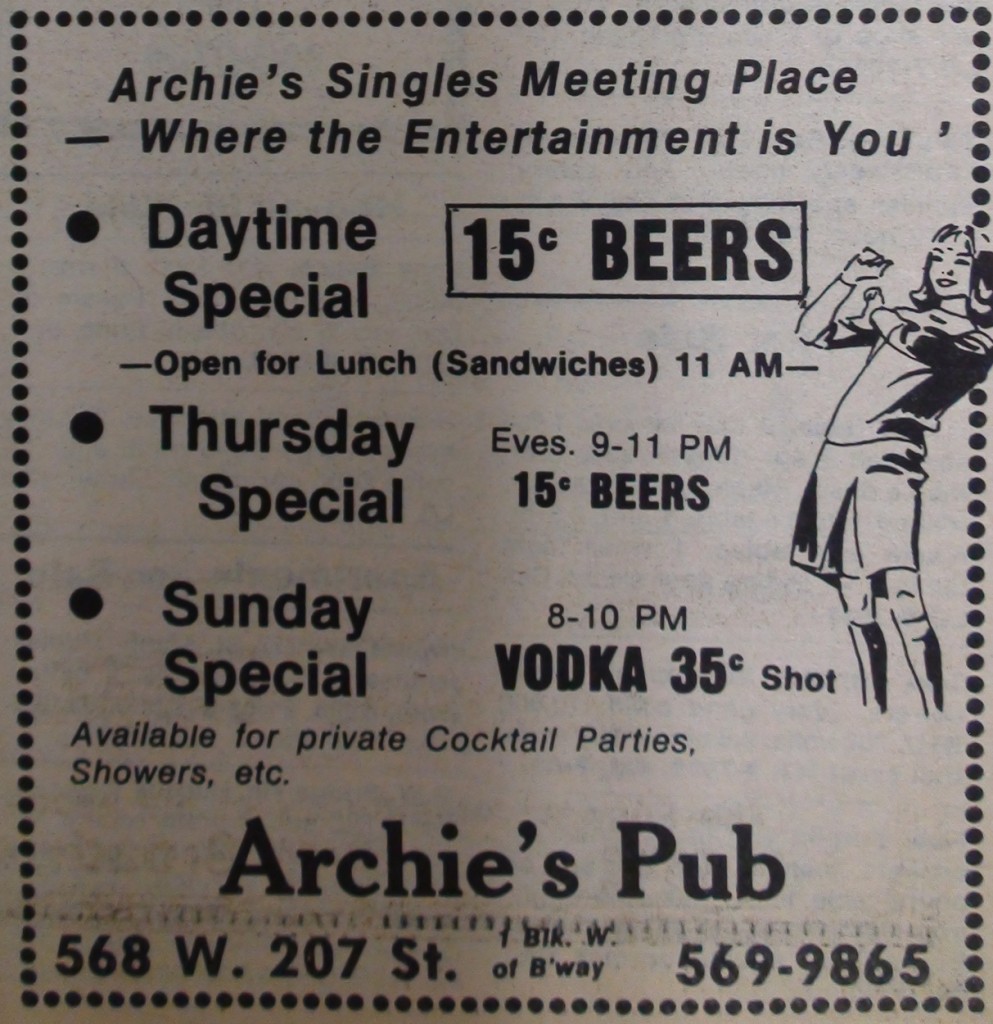

![Harper's Weekly cartoon, February 4, 1882.]()

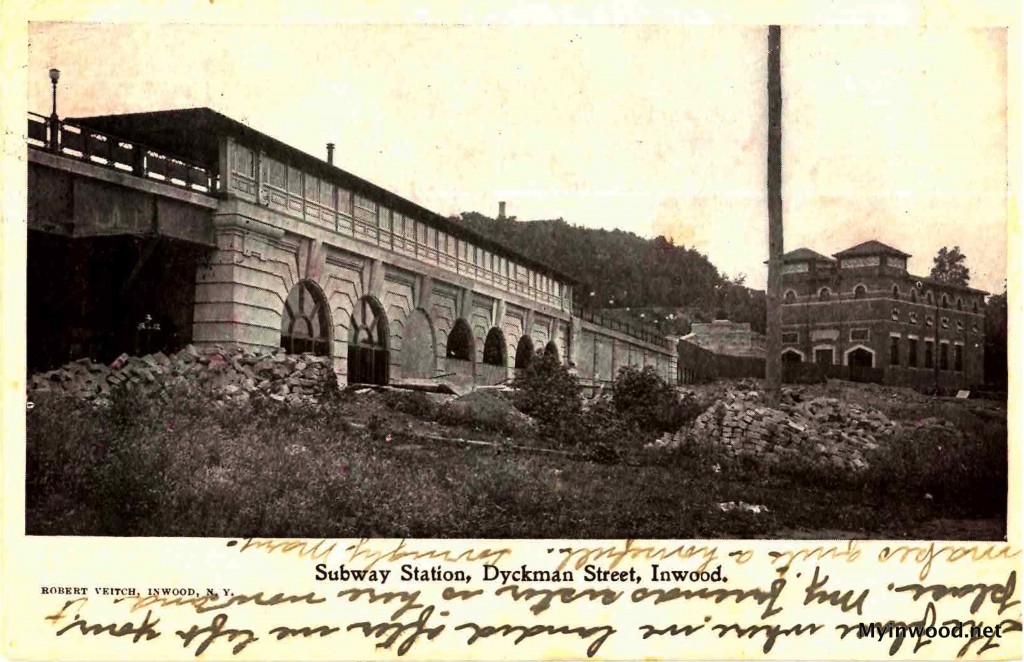

Harper’s Weekly cartoon, February 4, 1882.

Webster Wagner was not amused. He politely excused himself from the lavishly detailed palace car and stepped into the snowy night to investigate.

It was the last time he would be seen alive.

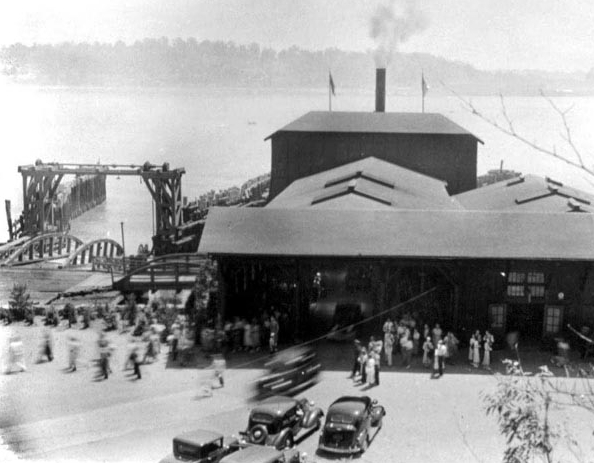

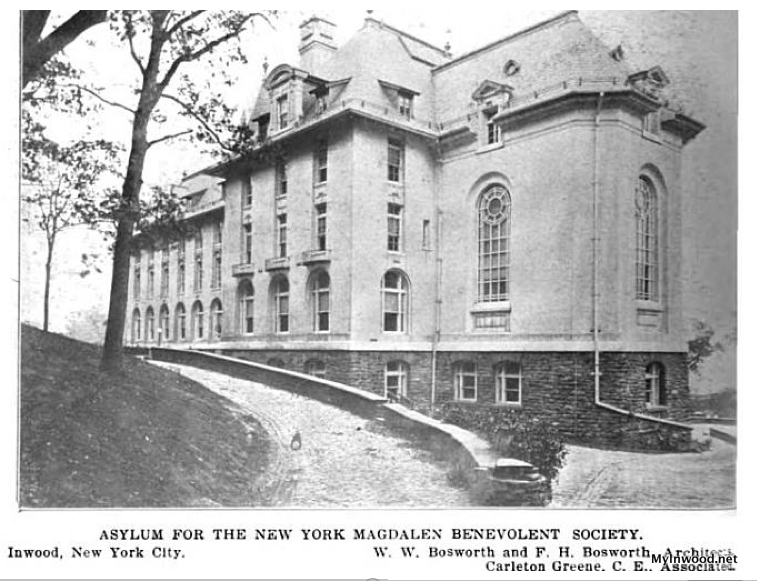

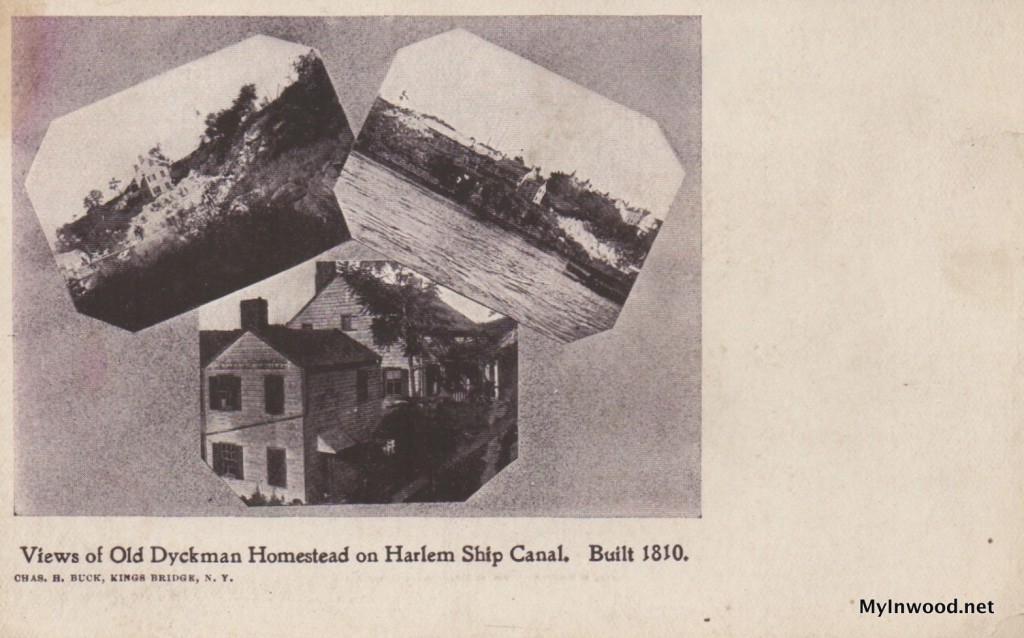

Standing above the cut William R. Murray, a brass moulder’s apprentice at the local foundry, watched as the pending tragedy played out before his eyes.

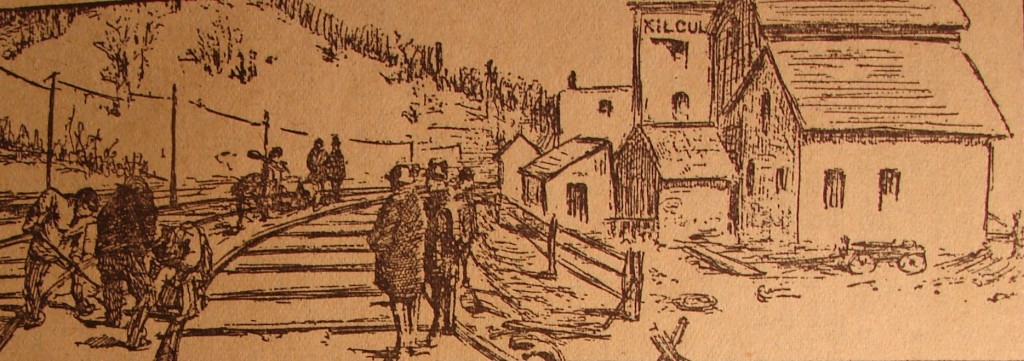

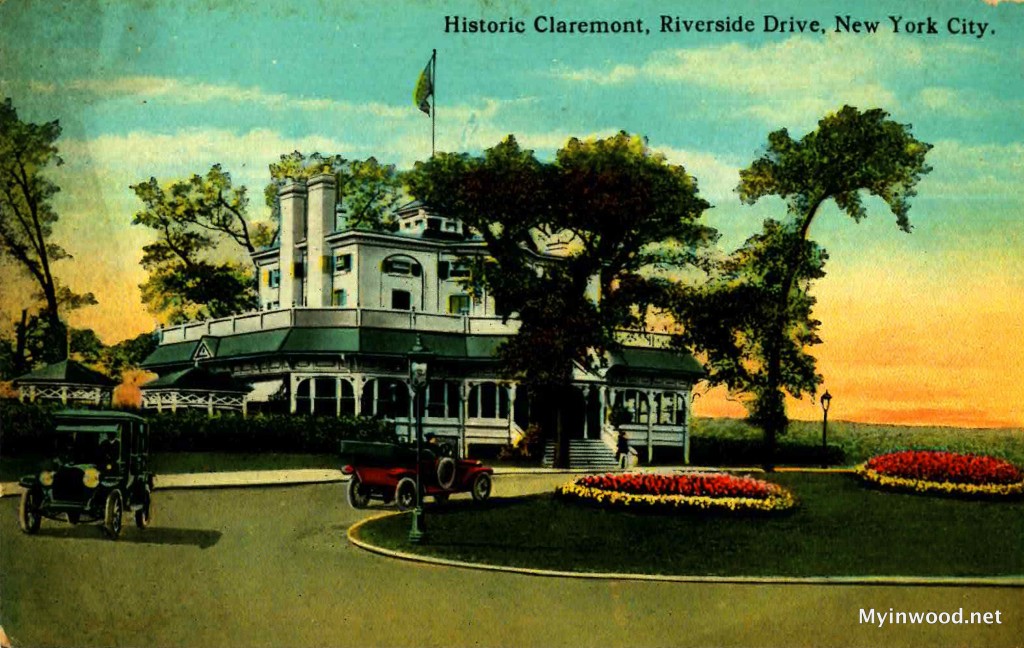

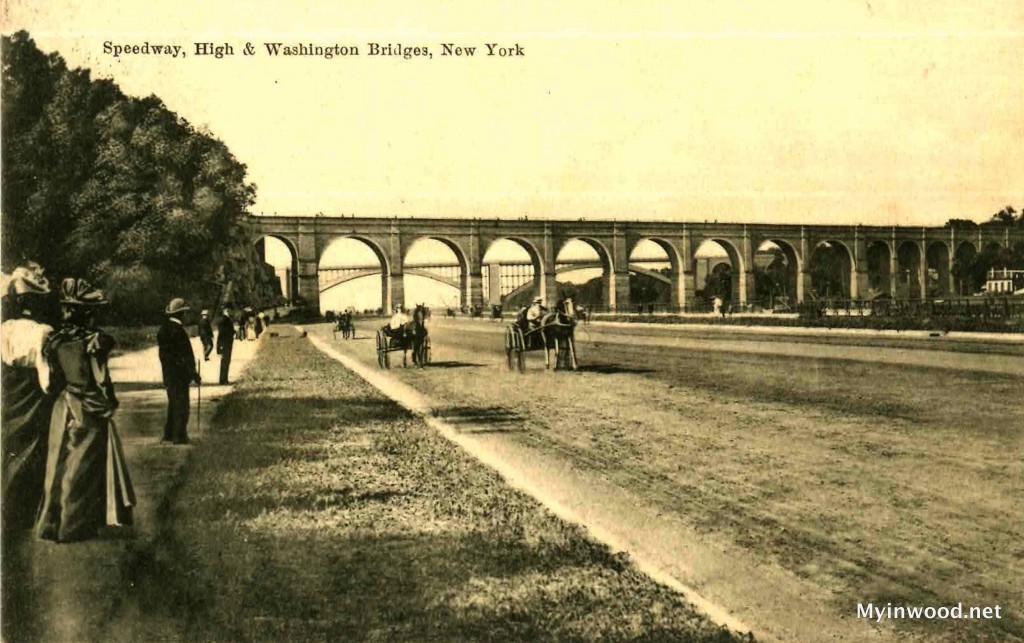

In later testimony, Murray recalled standing on the stoop of Kilcullen’s Hotel gazing curiously at the stalled train some 125 feet below the hotel and saloon.

Kilcullen’s was a popular watering hole for the foundry workers at the Johnson Ironworks, which once produced munitions alongside the peaceful banks of the Spuyten Duyvil—and on a Friday night the saloon was likely packed.

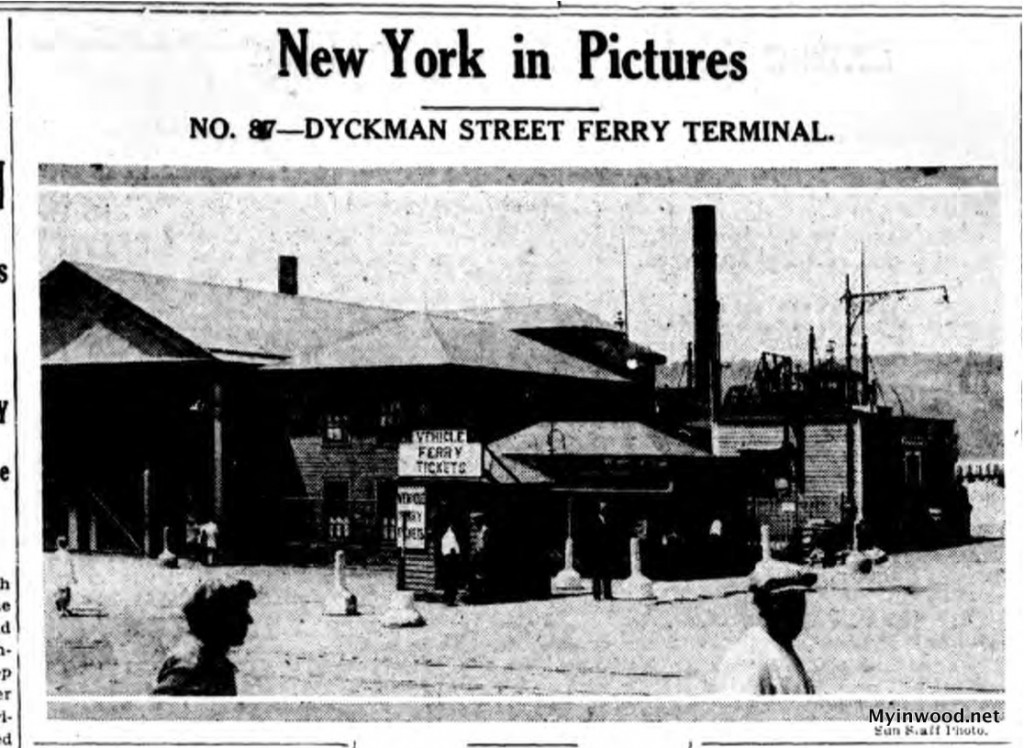

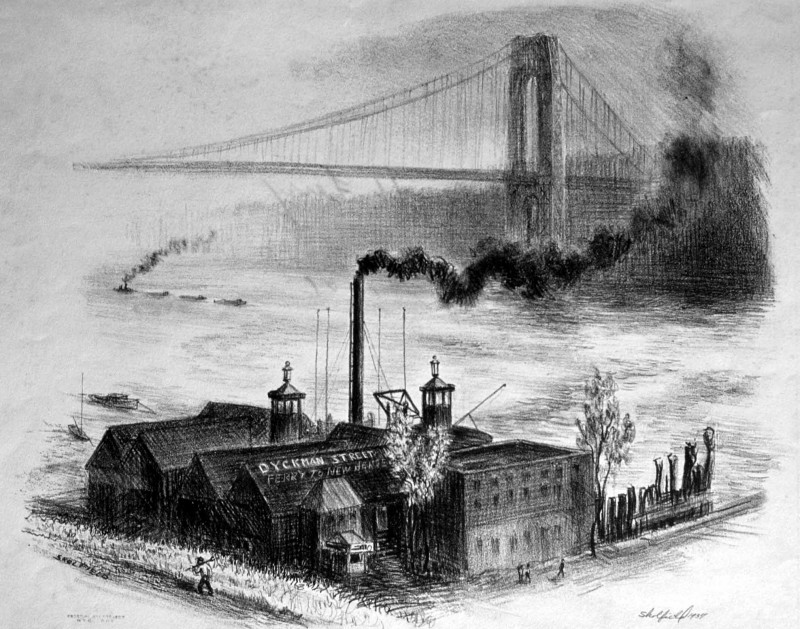

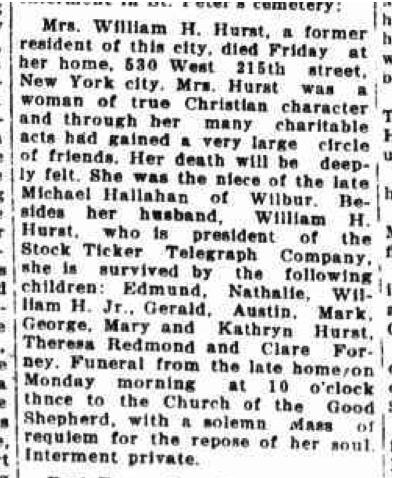

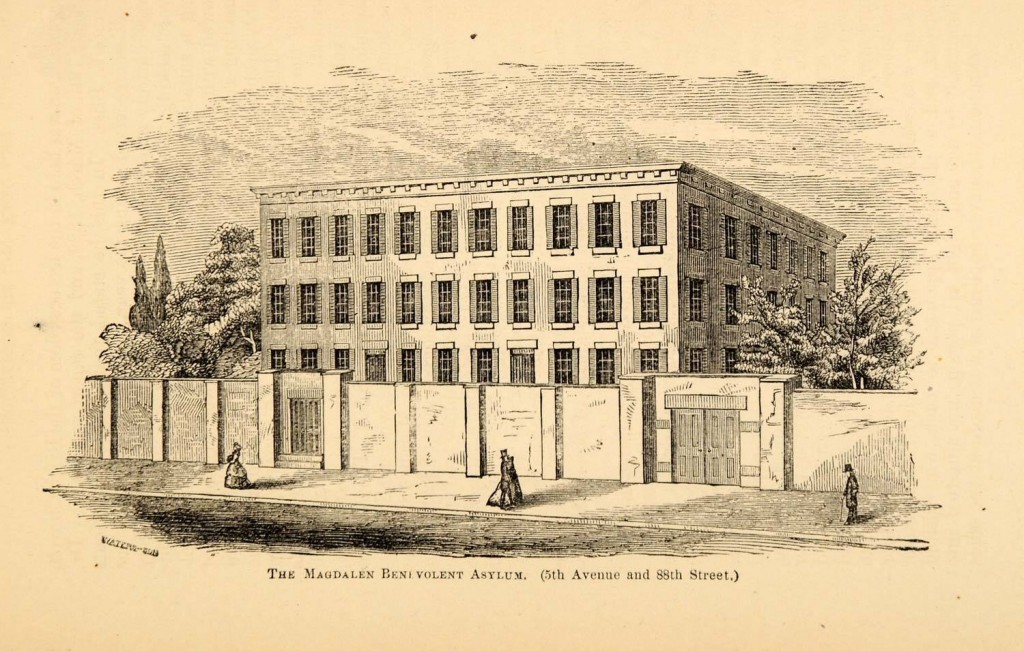

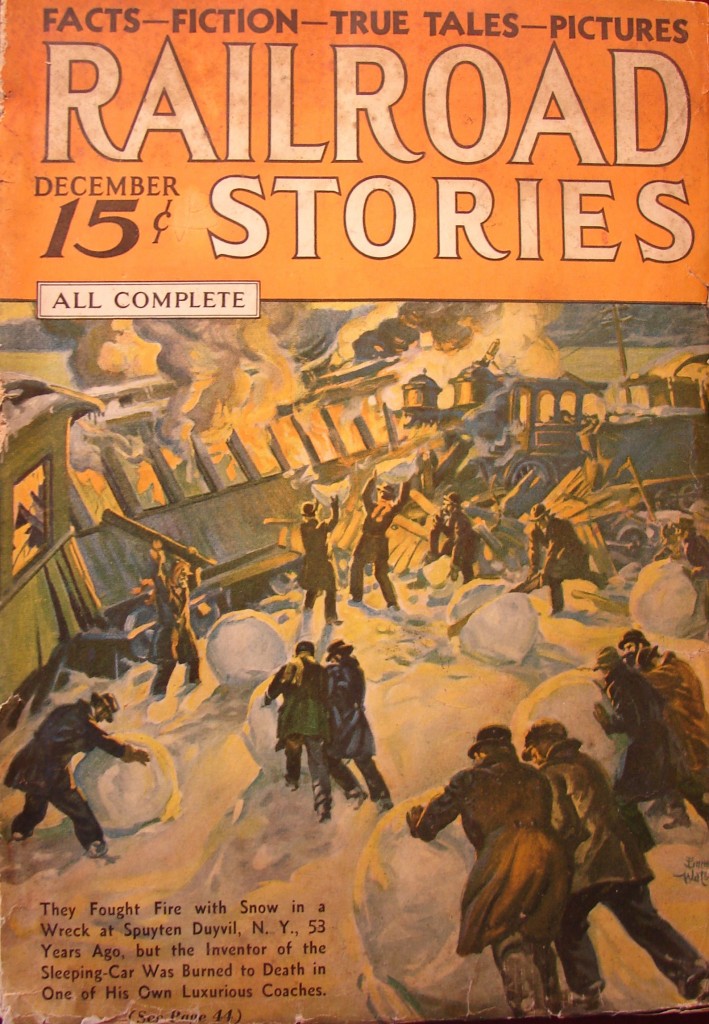

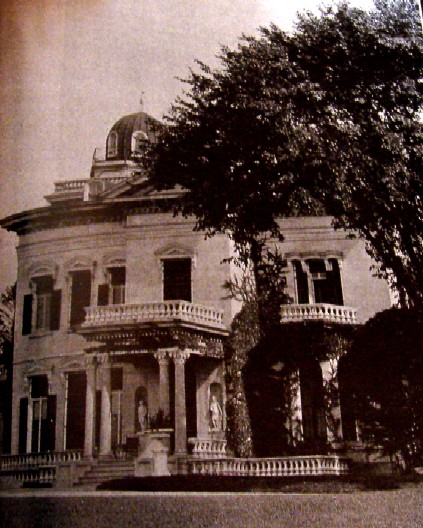

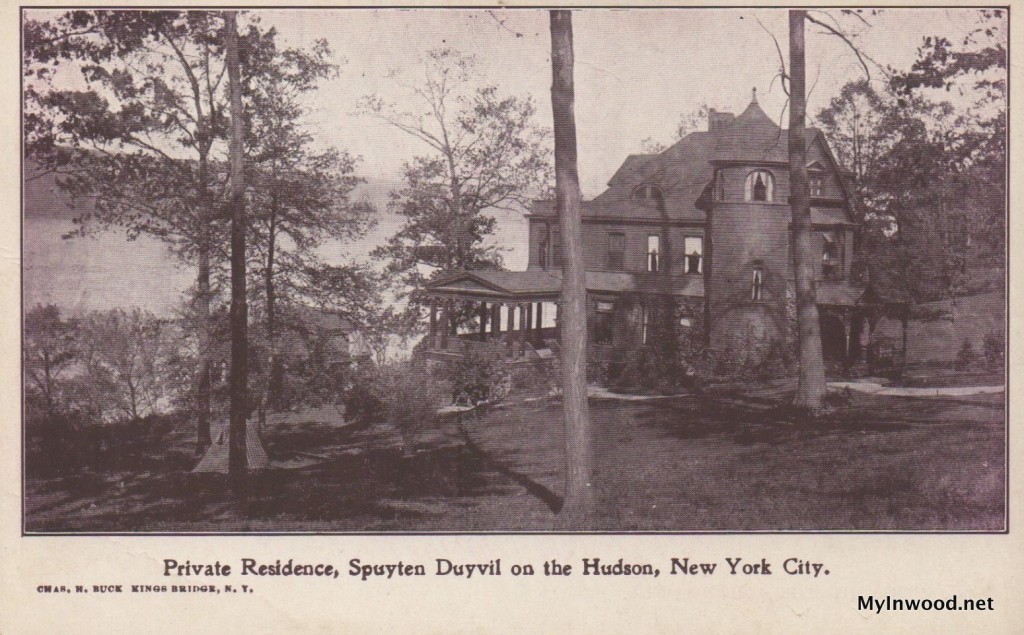

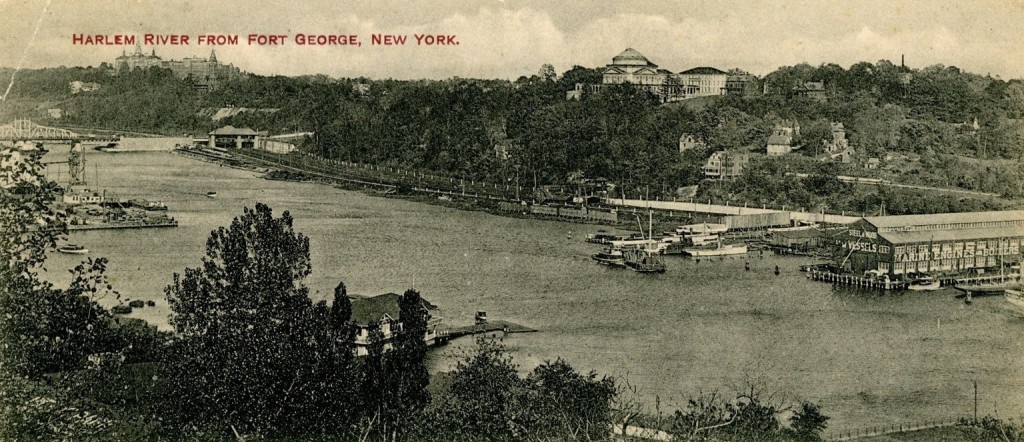

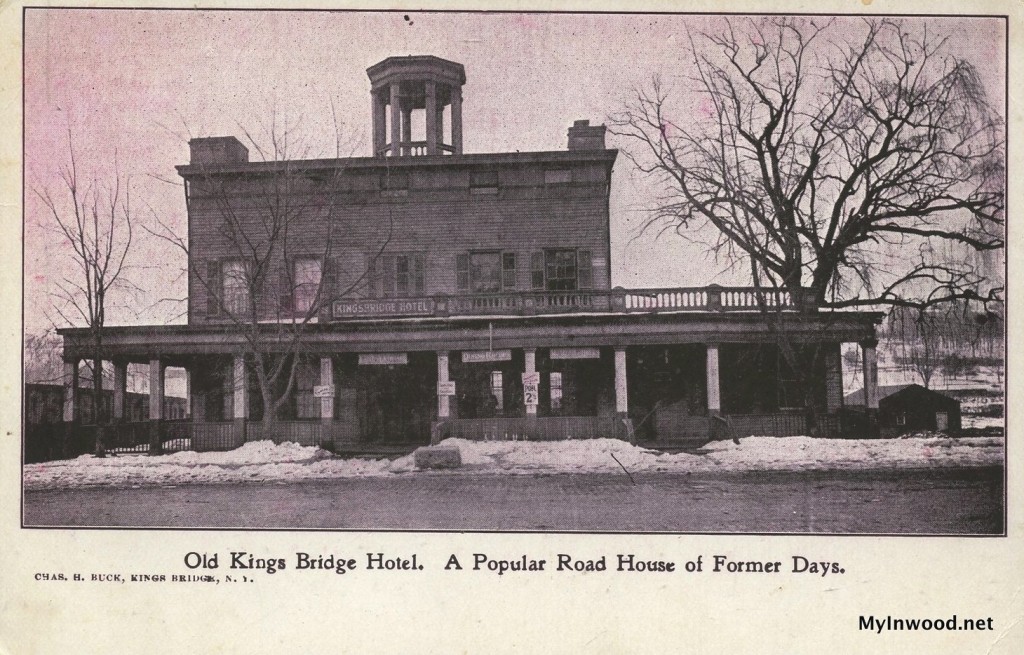

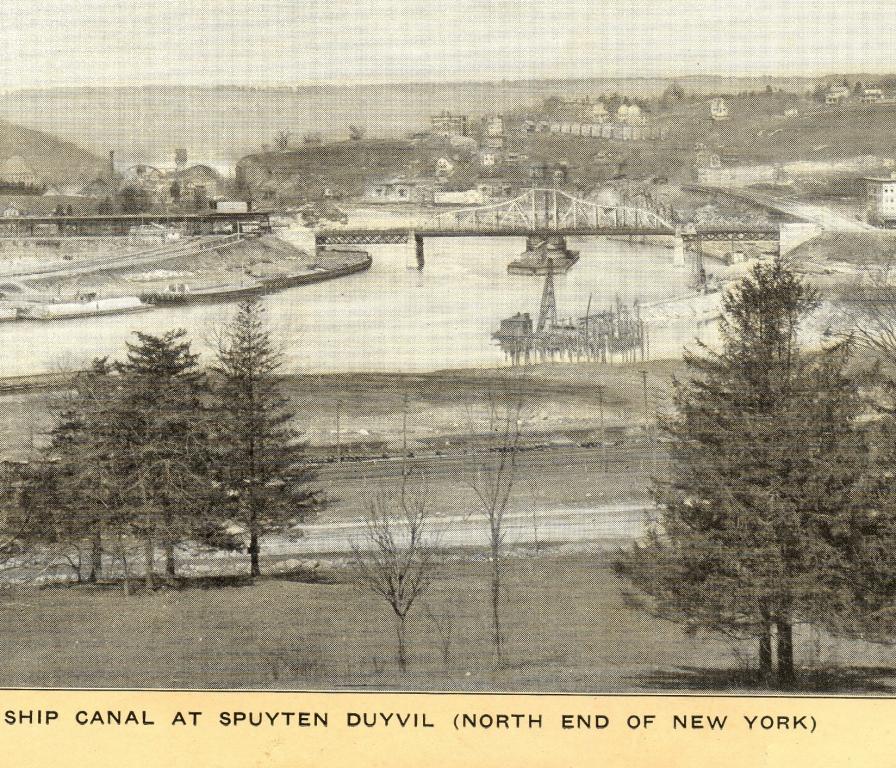

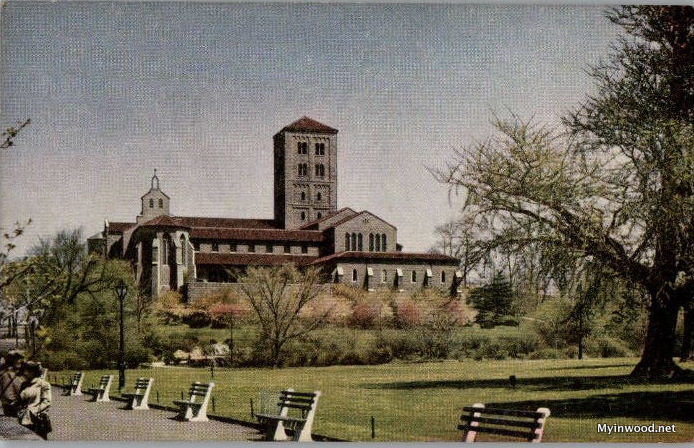

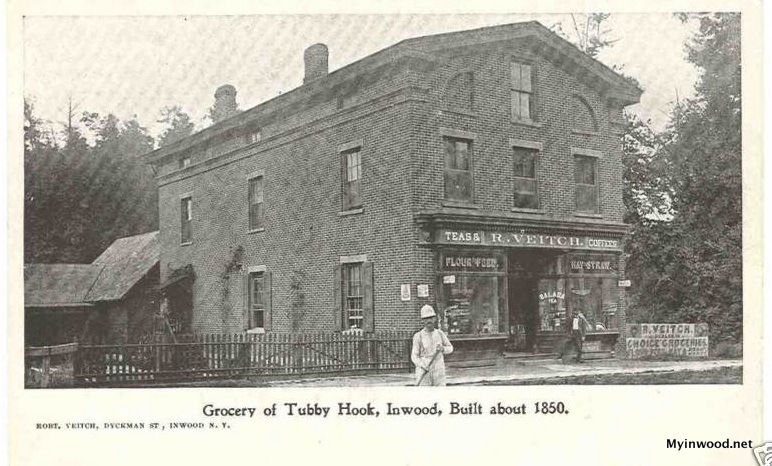

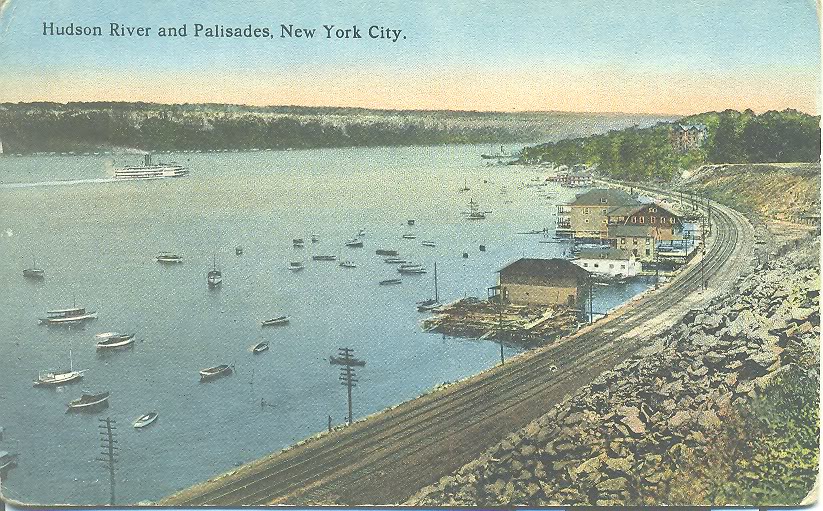

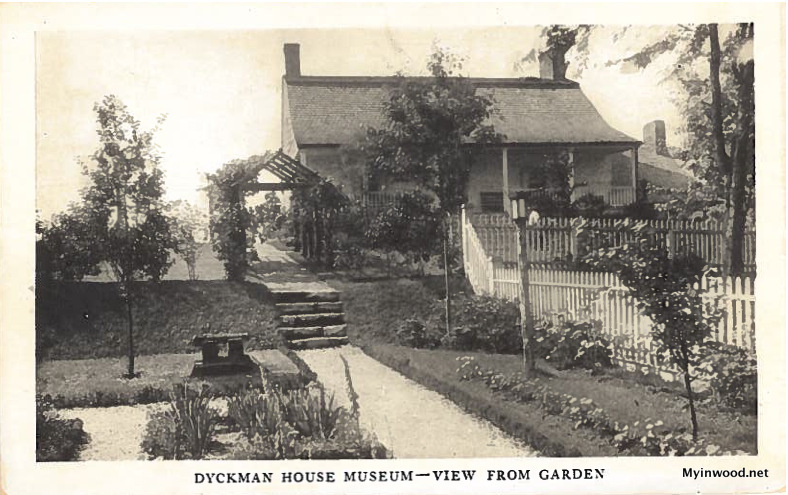

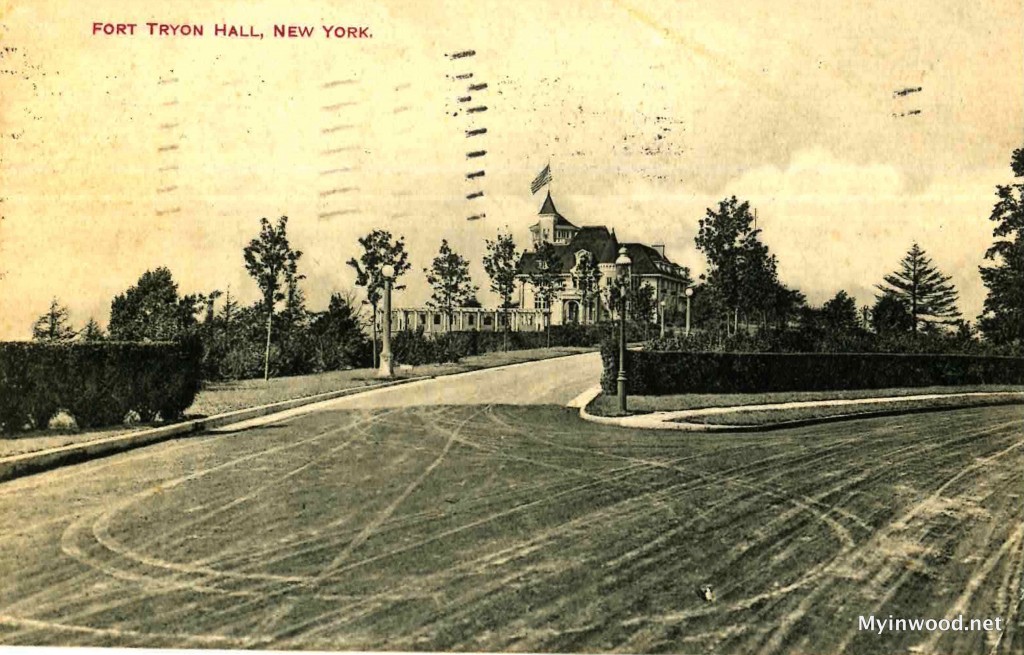

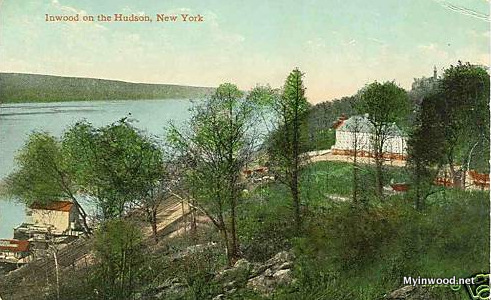

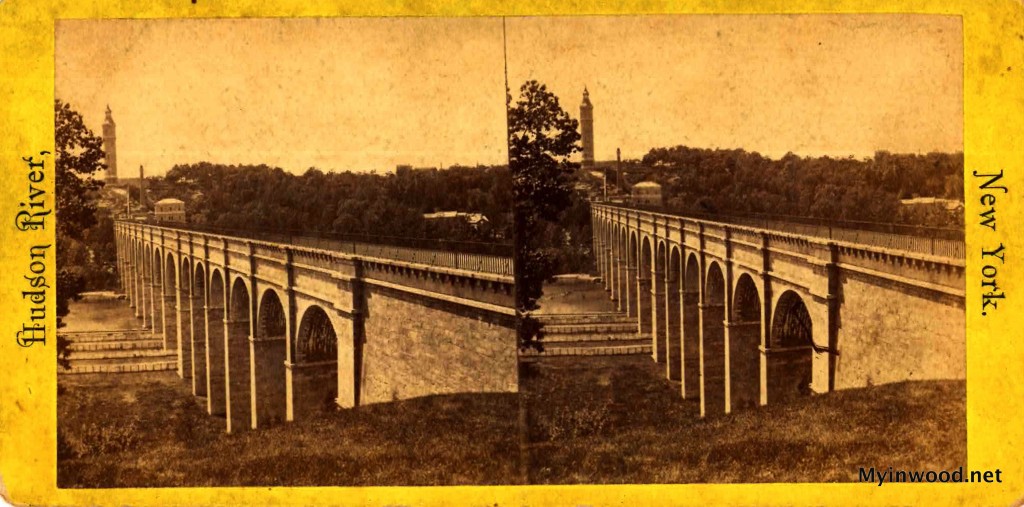

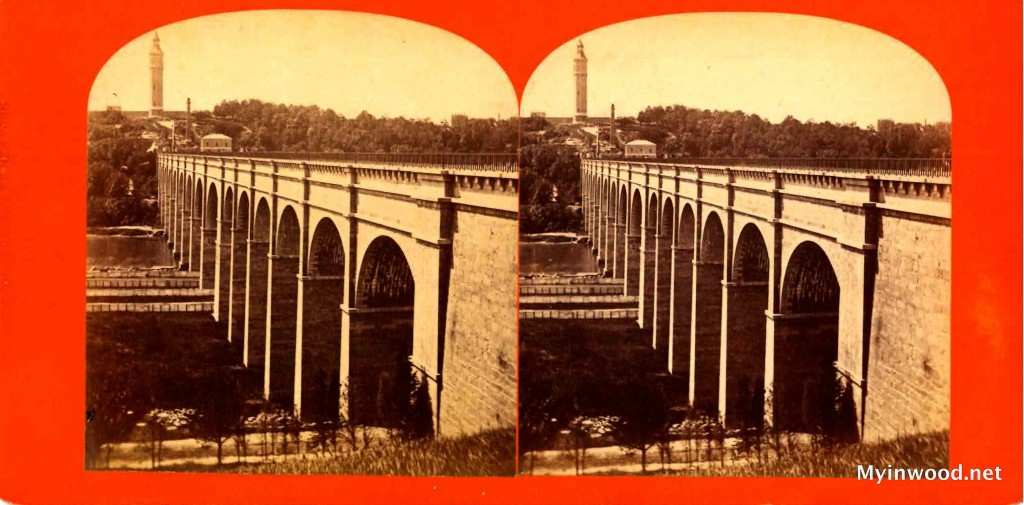

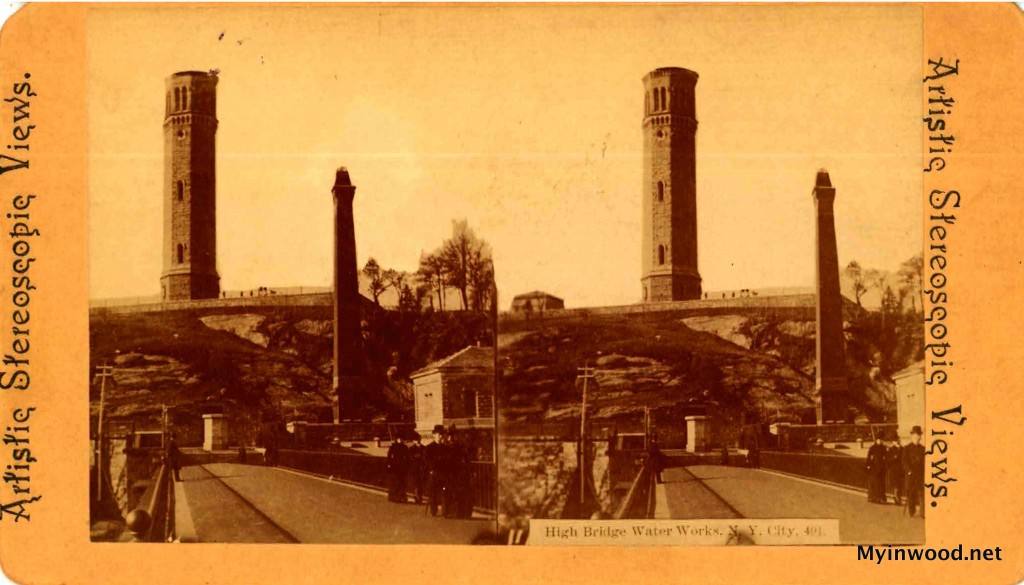

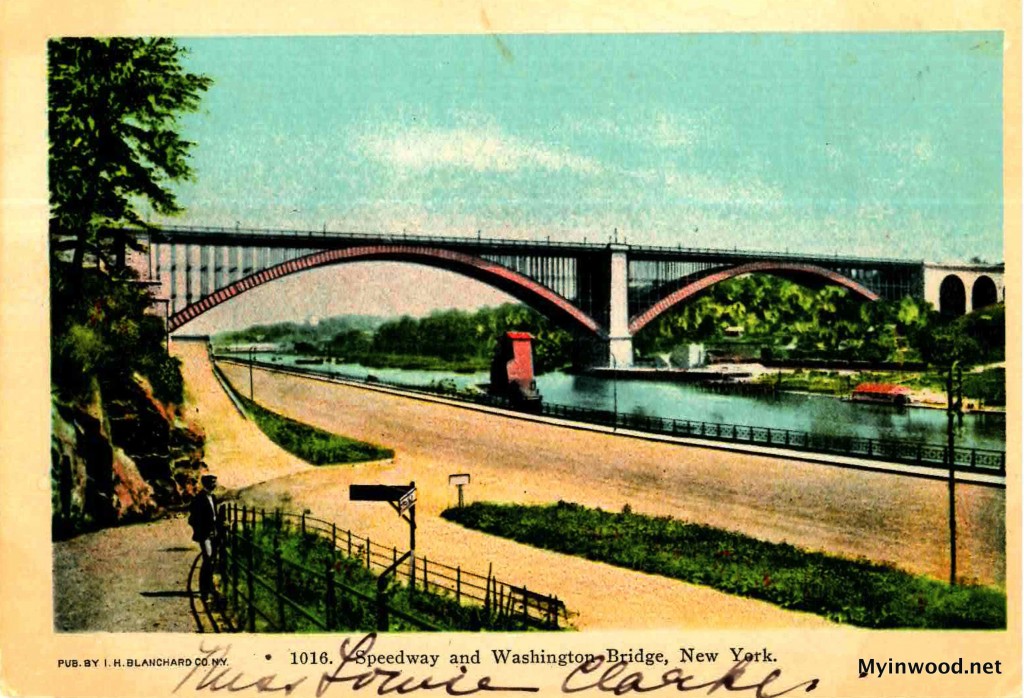

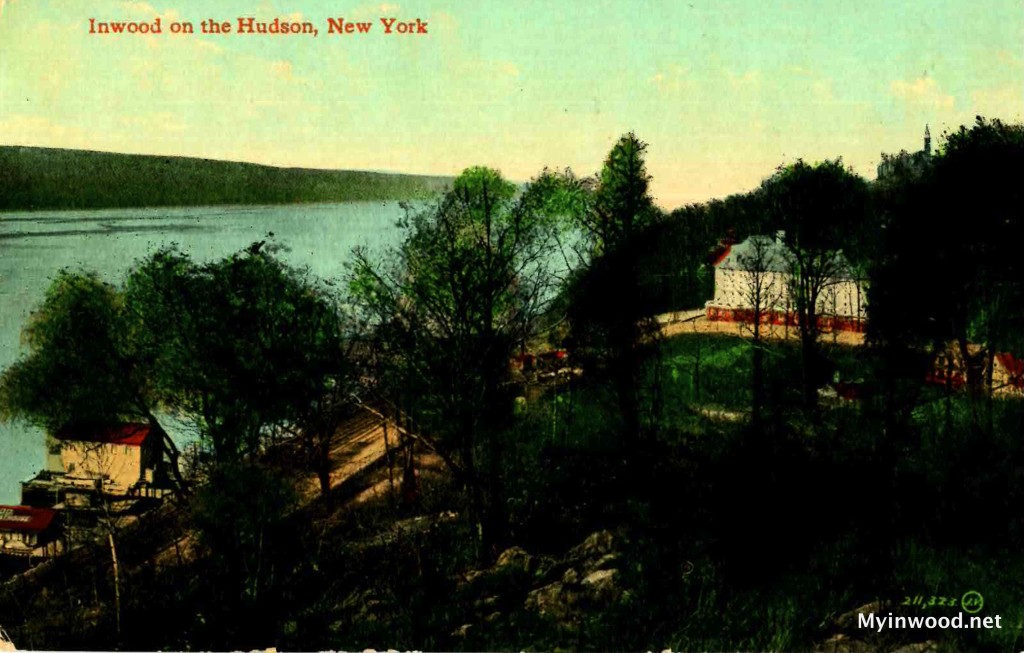

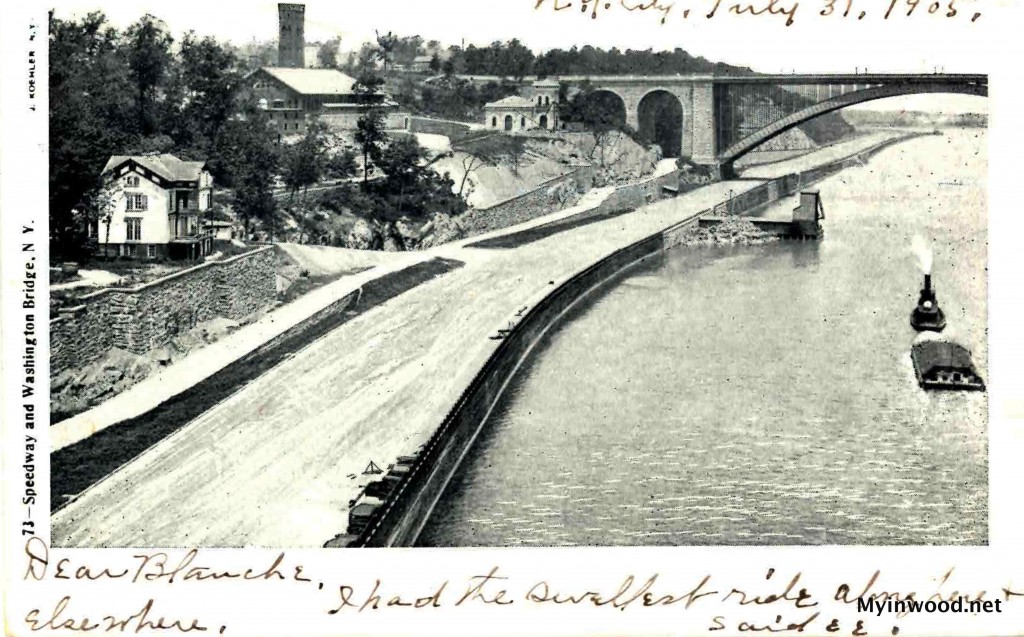

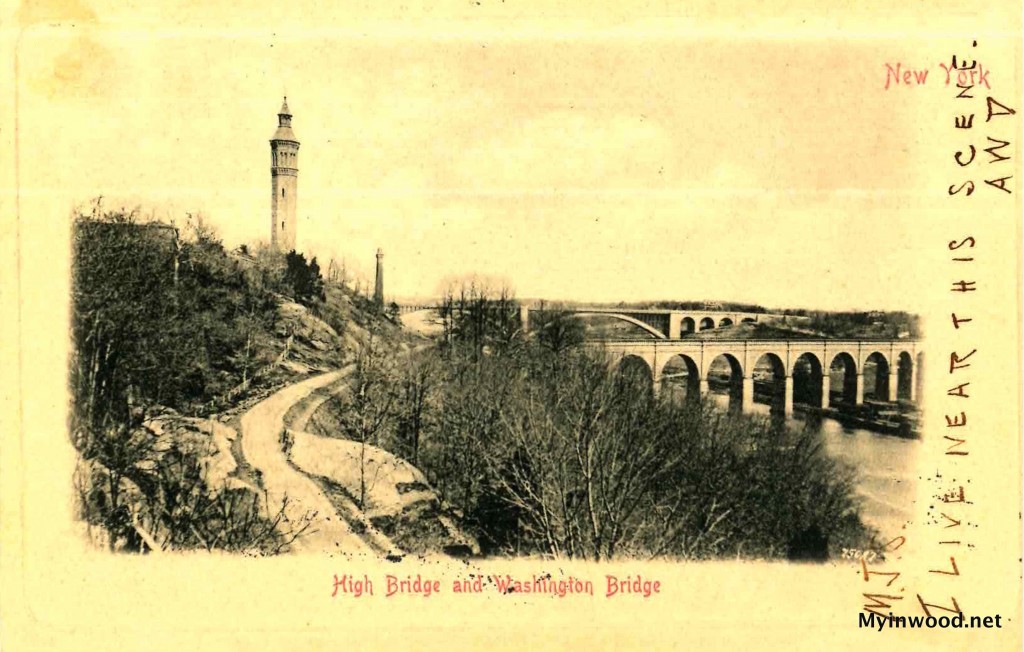

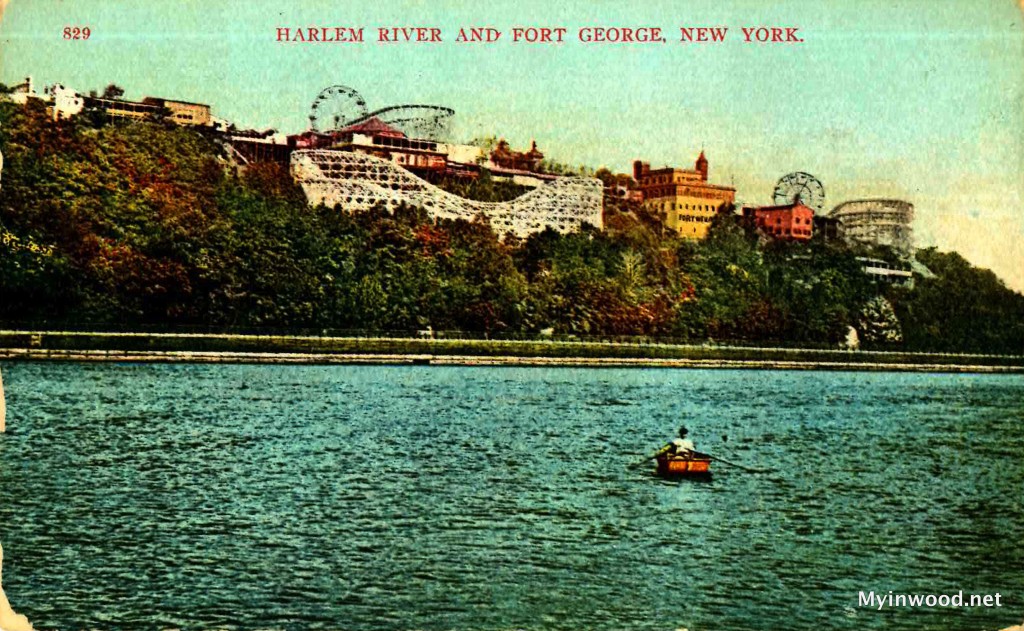

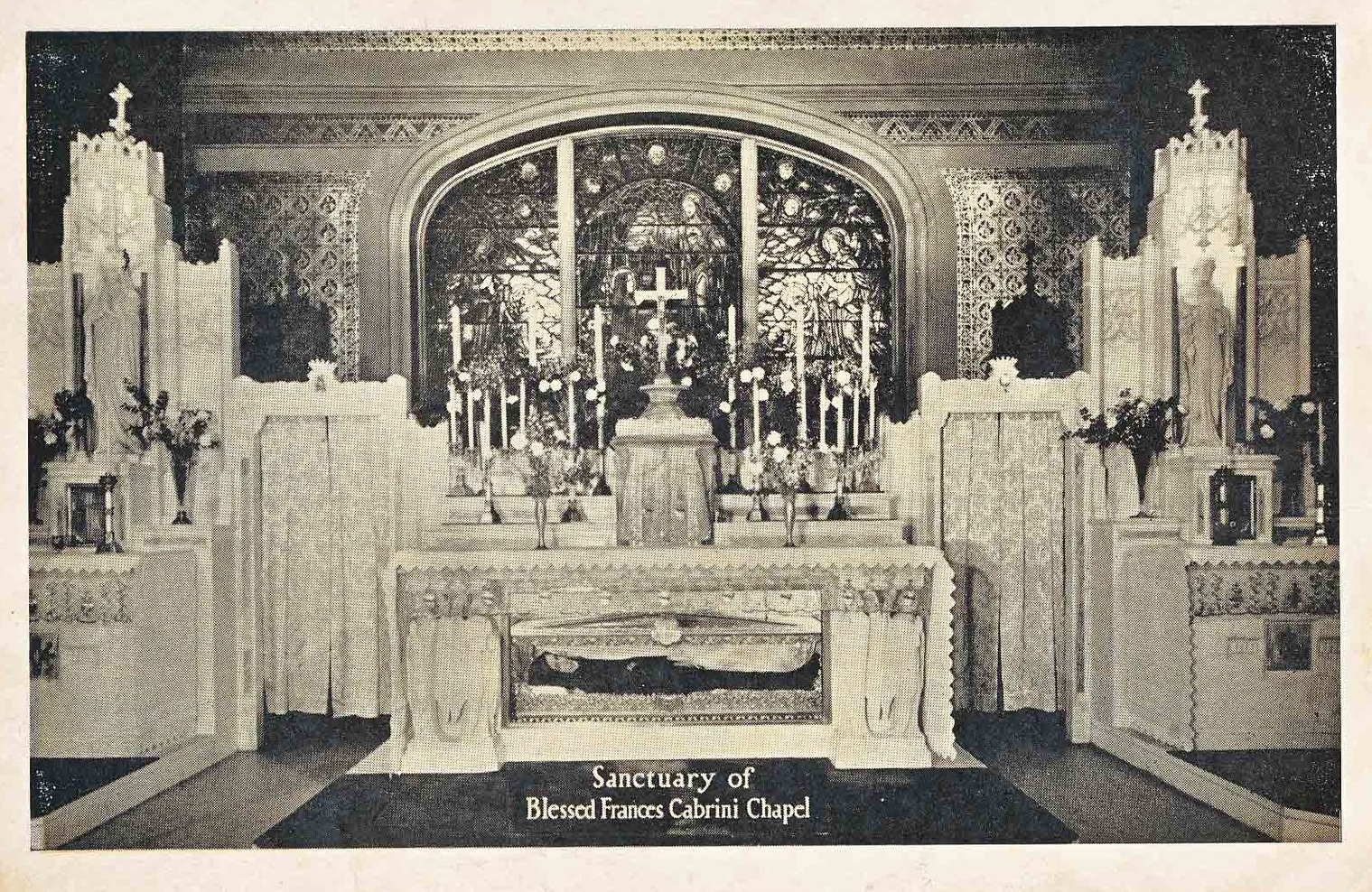

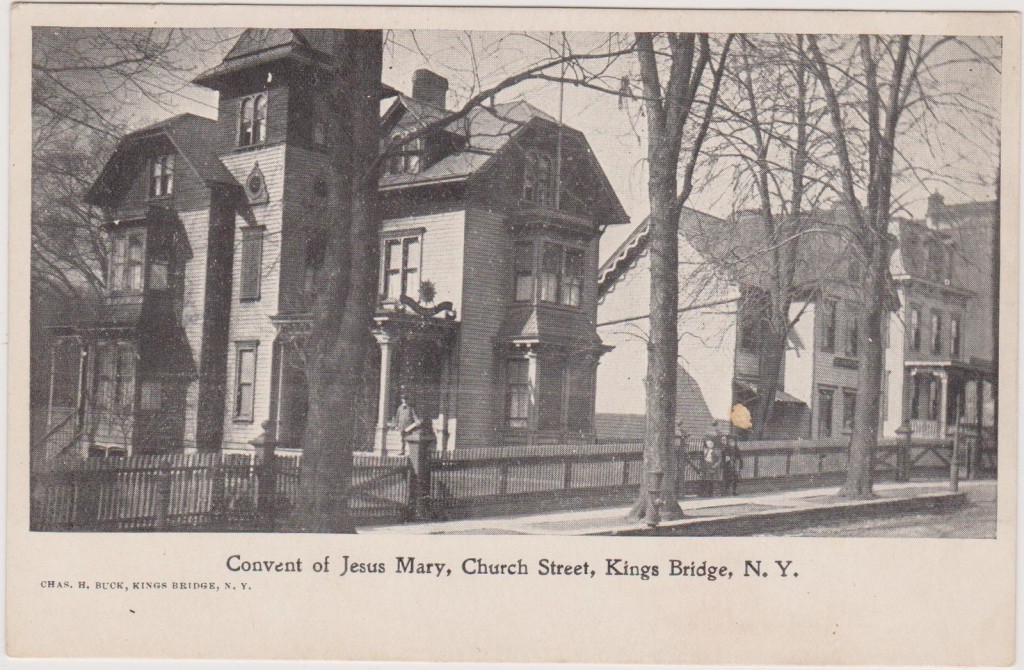

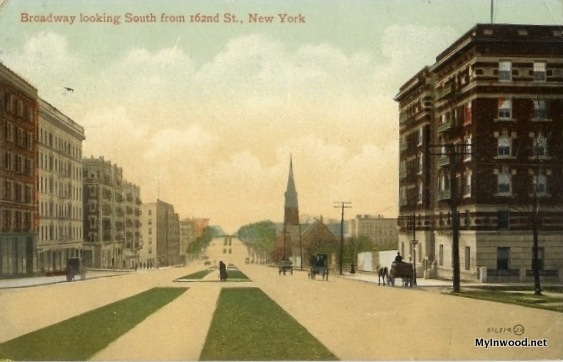

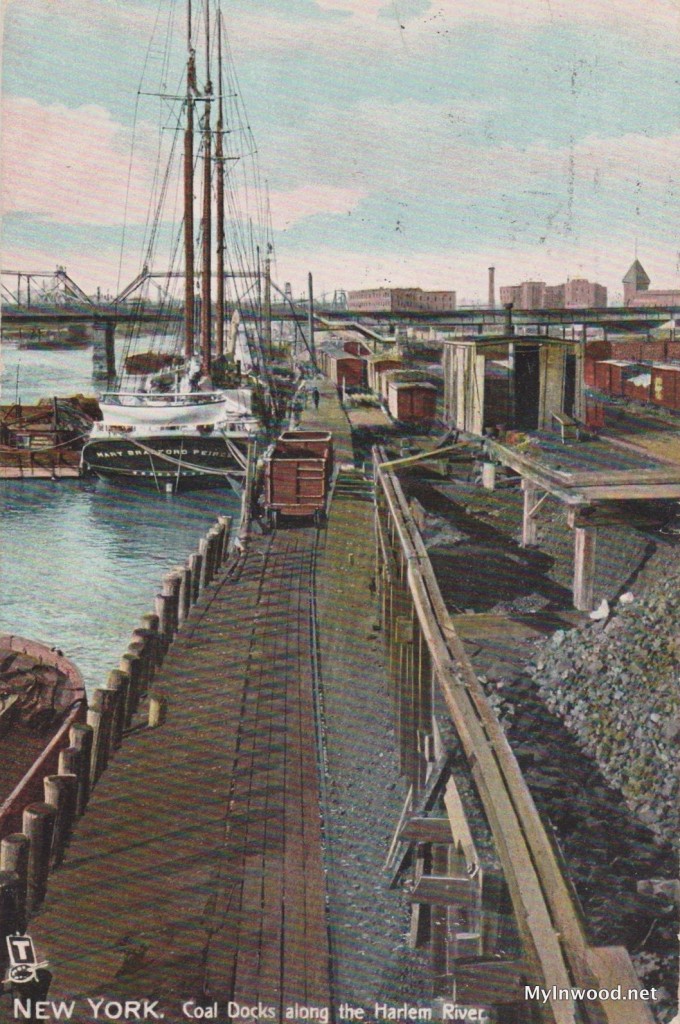

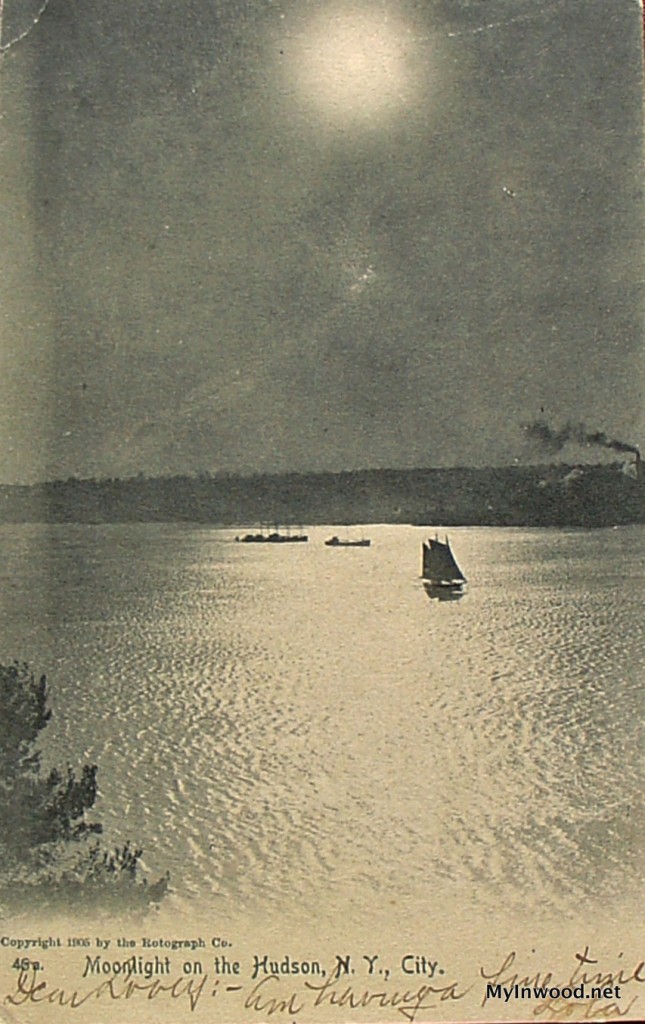

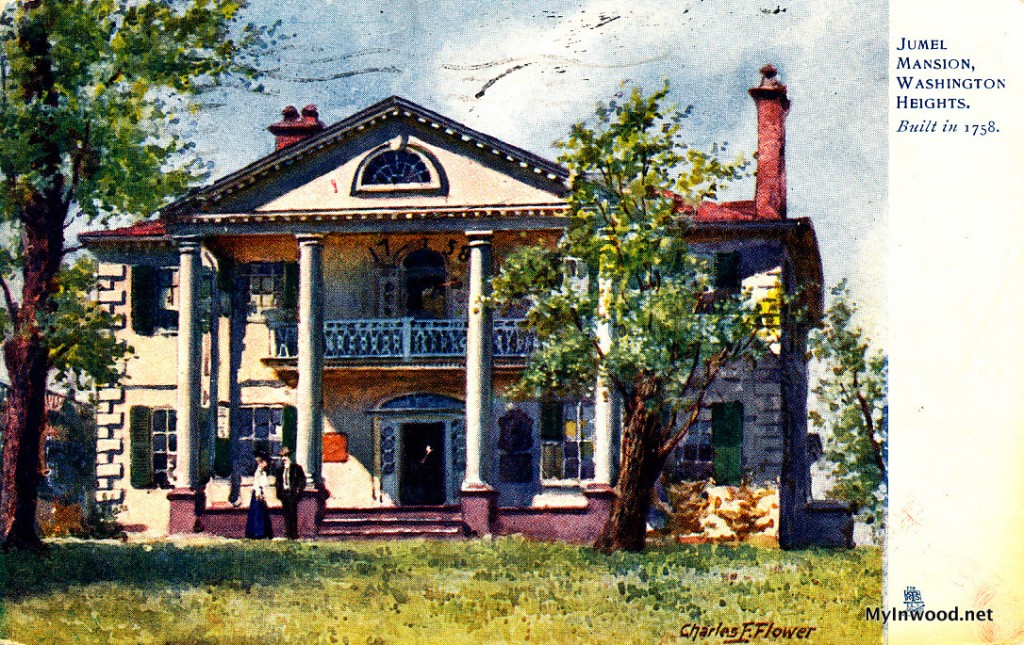

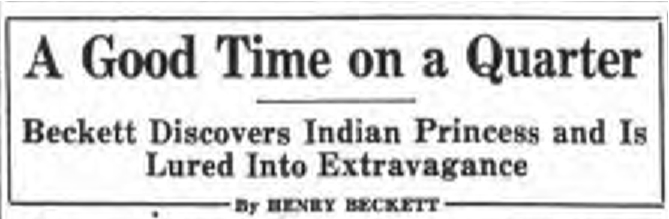

![Spuyten Duyvil in 1883, Johnson Ironworks on right and Inwood Hill on left.]()

Spuyten Duyvil in 1883, Johnson Ironworks on right and Inwood Hill on left.

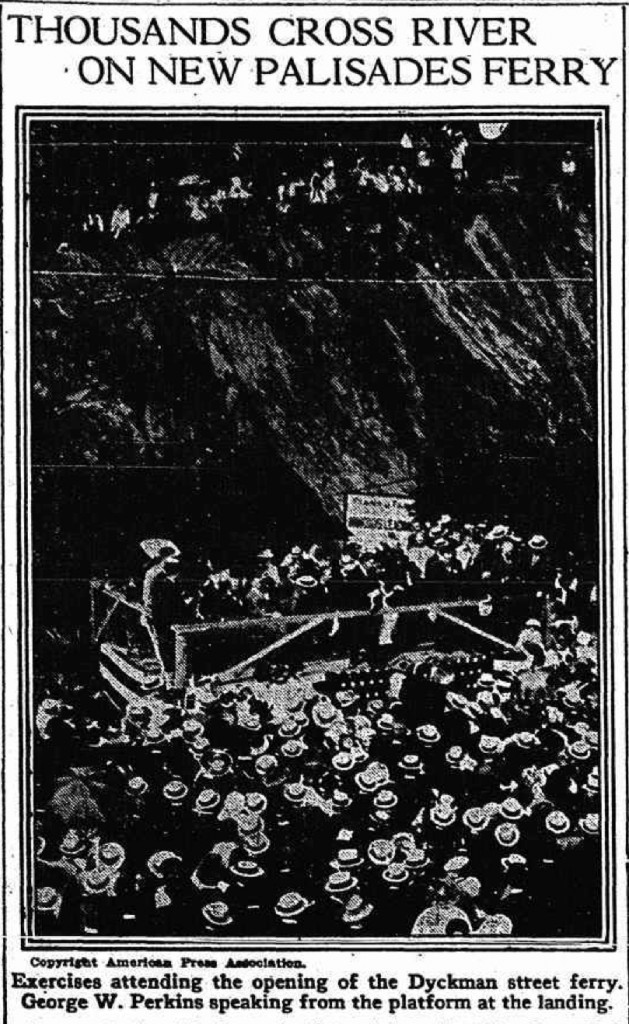

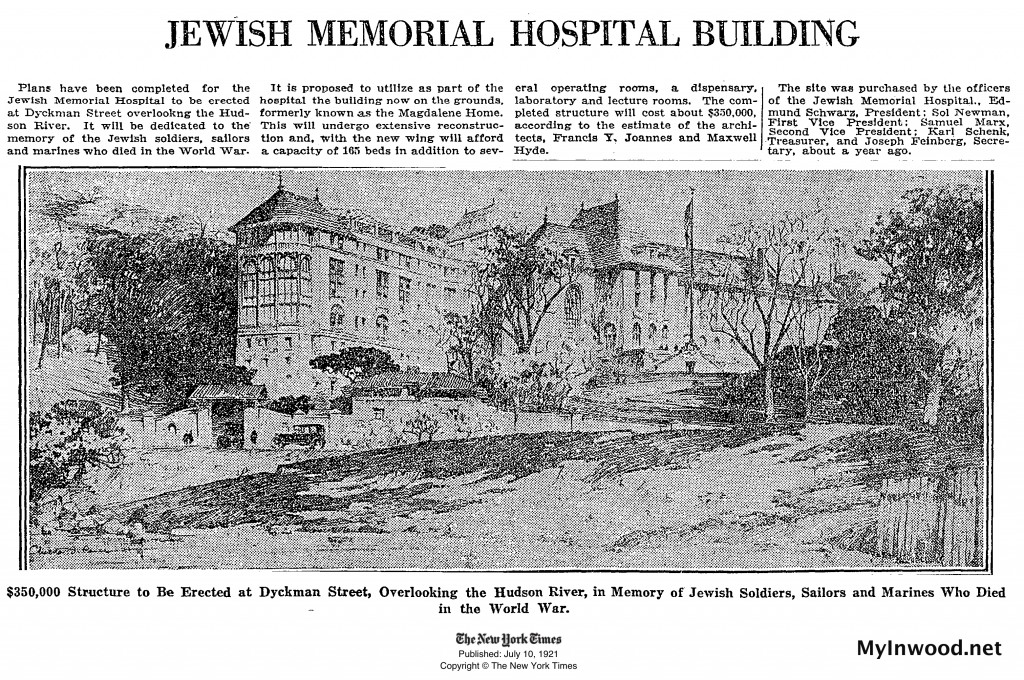

From the safety of his perch, Murray watch as another train, the Tarrytown Special, also heading south, sped through the cut on a collision course with the rear end of the unsuspecting Chicago Express.

A brakeman on the train from Albany, in a vain attempt to warn off the approaching train, ran towards the Tarrytown train frantically waving his signal lantern. The Tarrytown engineer sounded his whistle seconds before slamming into the stalled train.

Soon the pure, snow-covered banks of the Spuyten Duyvil were a kaleidoscope of blood and flames. Screams pierced the night as volunteers waded through the inferno to pull survivors out of the collision before they burned alive.

![Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, January 21, 1882.]()

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 21, 1882.

Other resourceful volunteers, worried the boilers might explode, rolled giant snowballs towards the overheated engine cars. Some even pelted survivors, their clothes ablaze, with snowballs in a desperate attempt to save human life.

The disaster had such a profound impact on the railroad industry that the Spuyten Duyvil disaster was featured on the cover of Railroad Stories, a pulp magazine for train enthusiasts, more than half a century later.

Below, in its entirety, is the harrowing account published by Railroad Stories in 1935.

Railroad Stories, 1935

The Wreck at Spuyten Duyvil

By H.R. Edwards

A light snow was swirling around the Chicago-New York Express as she double-headed out of Albany at 3:06—twenty-six minutes late—on a gray afternoon of 1882, straightened her “string of varnish” after leaving the yards, and settled down for the 142-mile run to New York City.

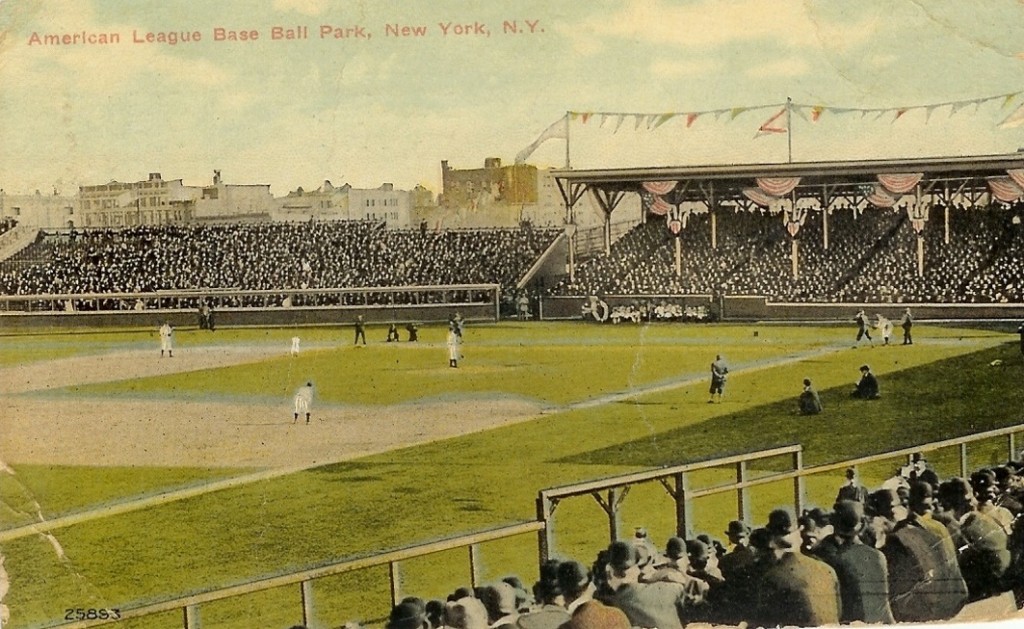

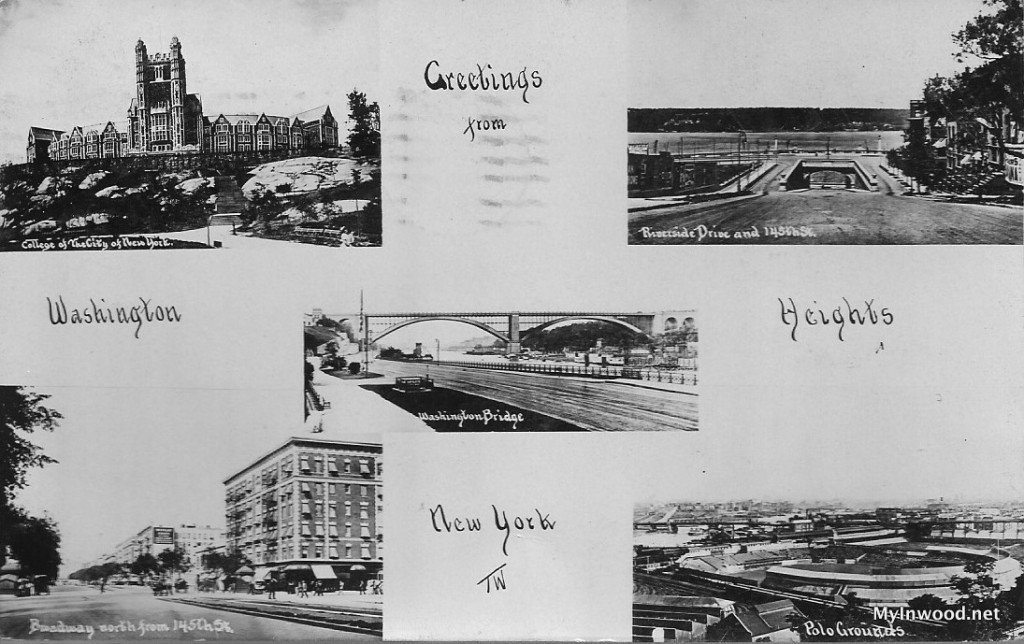

It was Friday the 13th. Although there were thirteen wooden cars in that train, the possibility of a jinx didn’t seem to worry the seventy-seven politicians who were traveling southward from the New York State capital on free passes given by the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad.

They laughed and roughhoused like schoolboys on a holiday. As a matter of fact, that’s just what it was. The State Legislature had adjourned for the weekend, and they were going back to the big city—back to the bright lights of Broadway and the three-story brownstone mansions of Twenty-third Street.

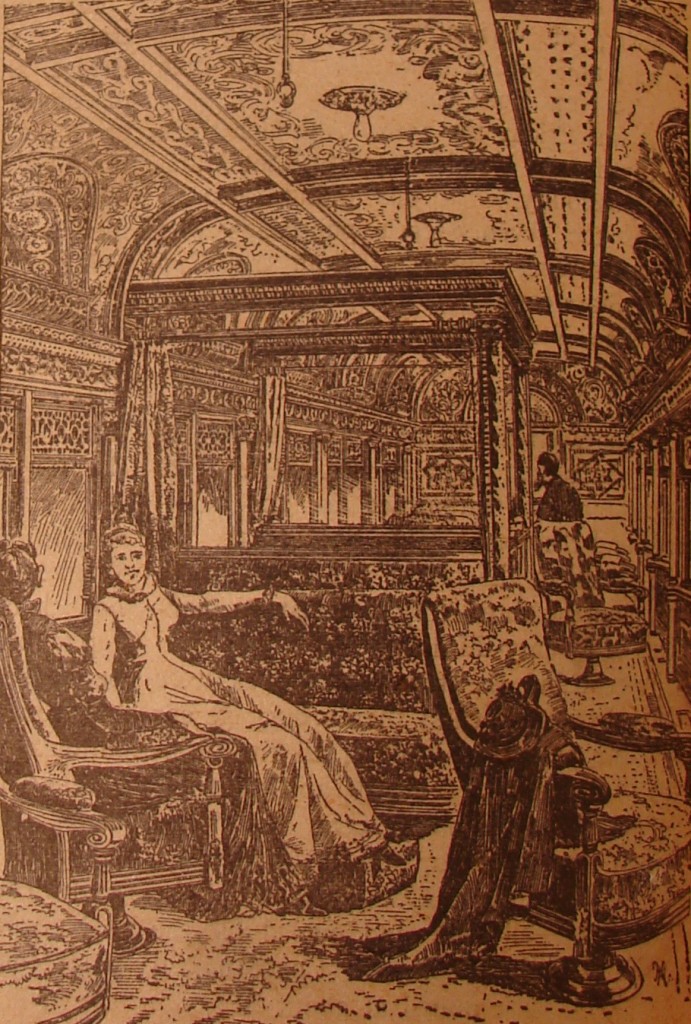

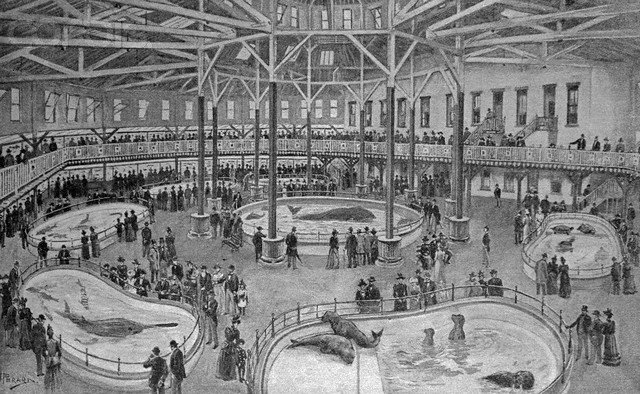

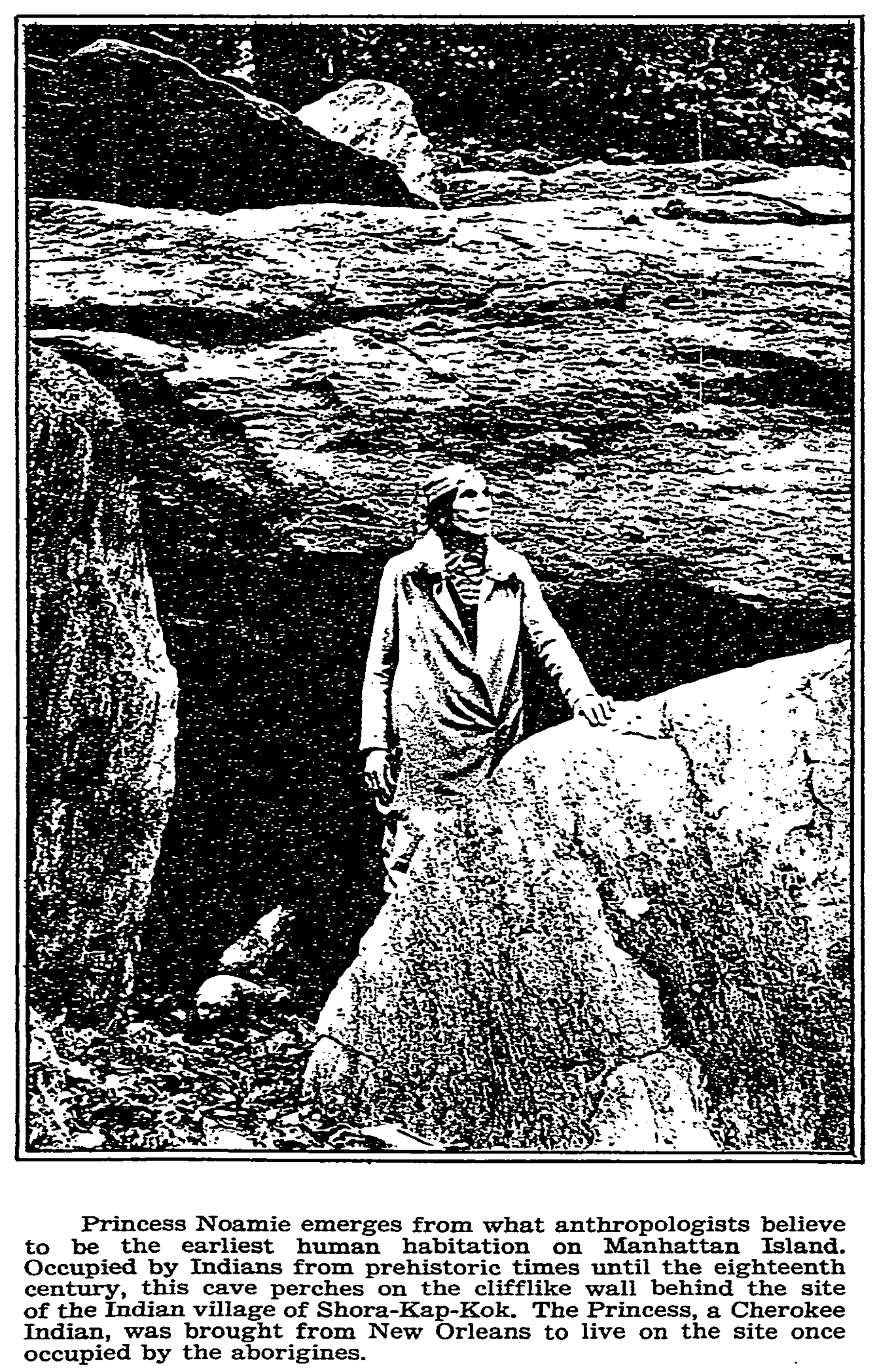

![Interior view of parlor car showing the luxury of travel in the 1880's. Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.]()

Interior view of parlor car showing the luxury of travel in the 1880′s. Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.

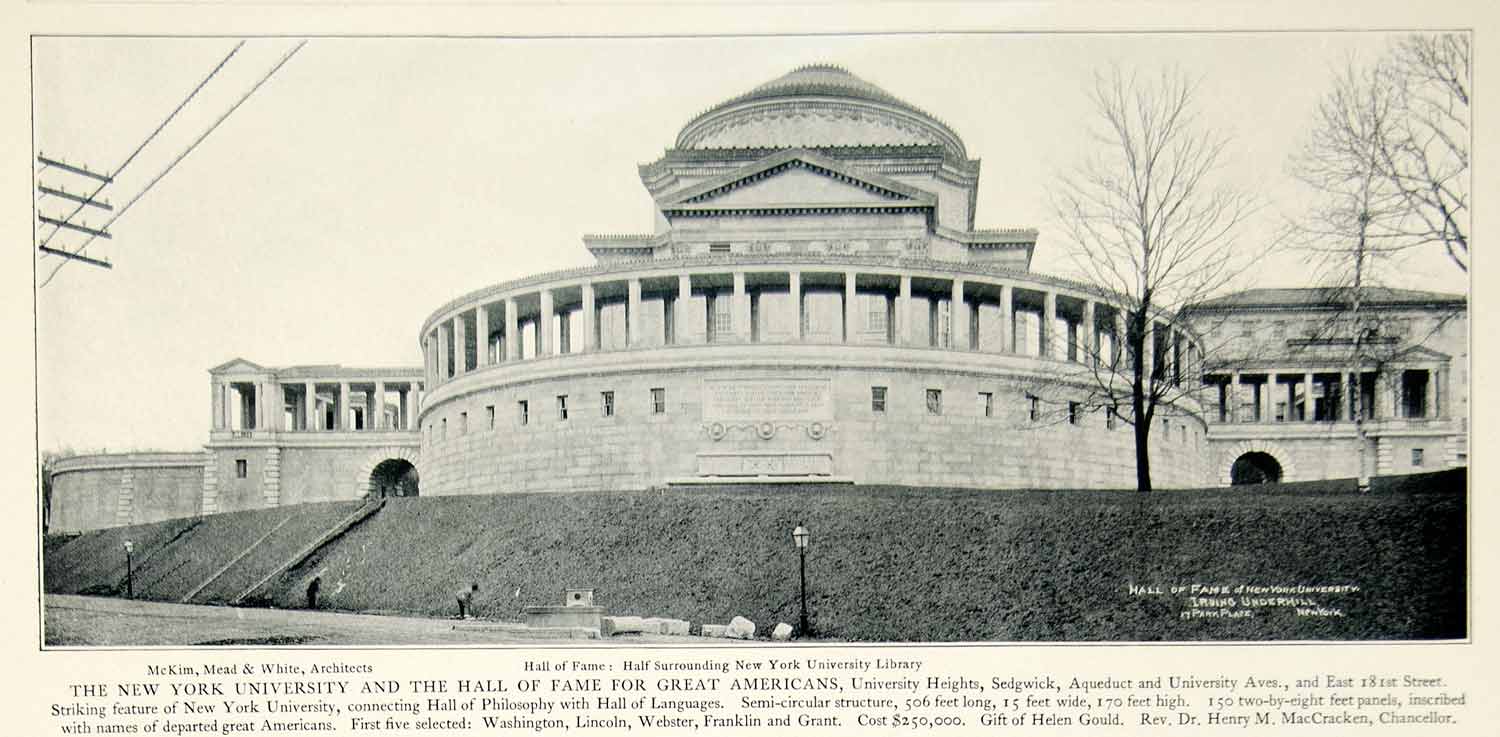

Just behind the two locomotives were coupled two mail cars; then a baggage car and four passenger coaches, all the property of the railroad. Lastly, and most important, came six parlor cars: the “Red Jacket,” the “Sharon,” the “Vanderbilt,” the “Minnehaha,” the “Empire,” and the “Idlewood” –all built and owned by the Wagner Drawing-Room Car Company, of New York; each valued at about $17,000.

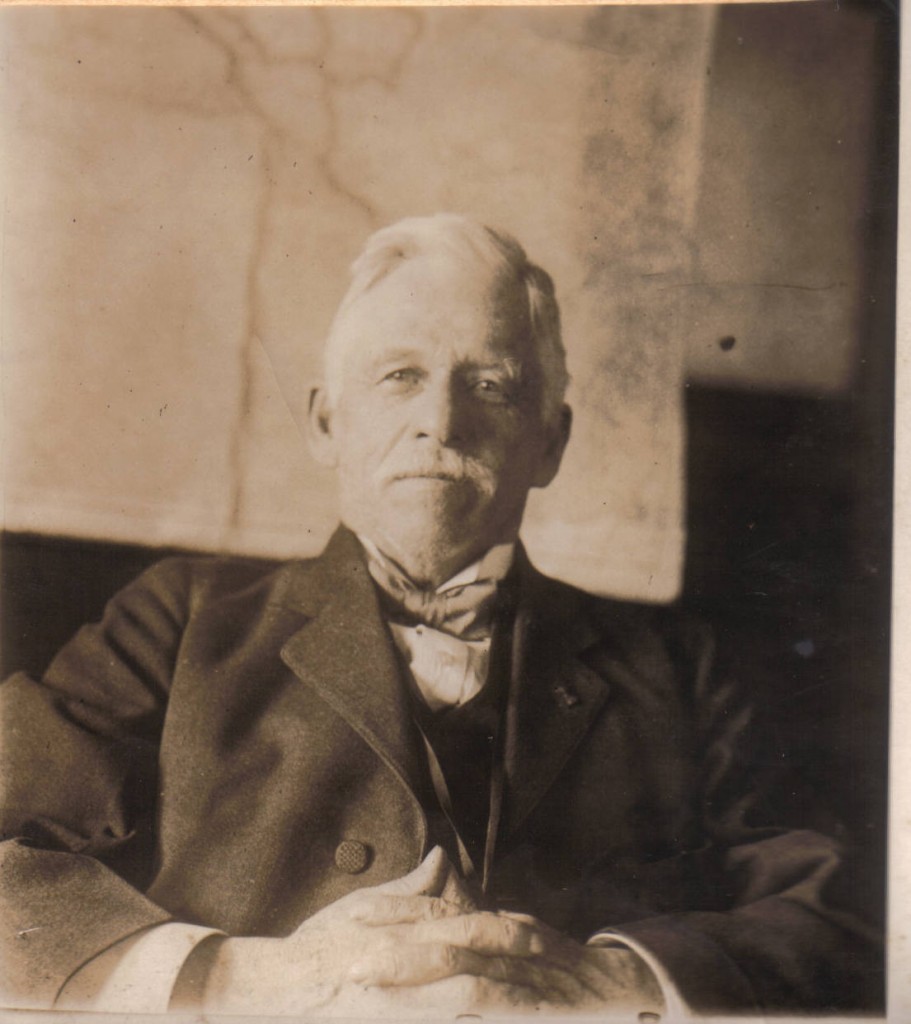

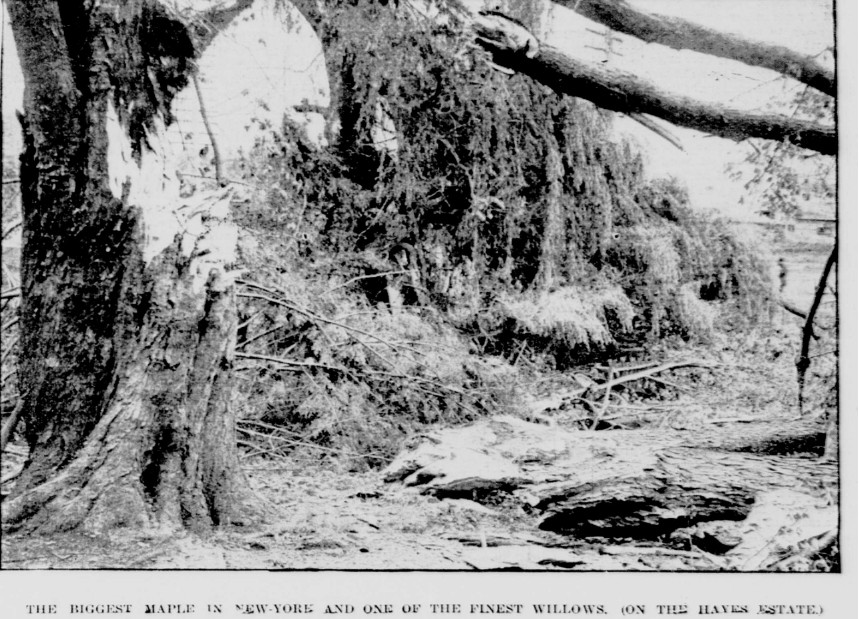

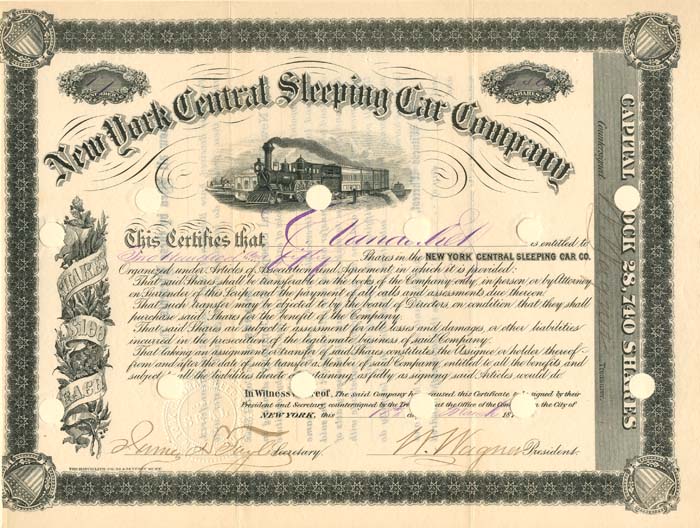

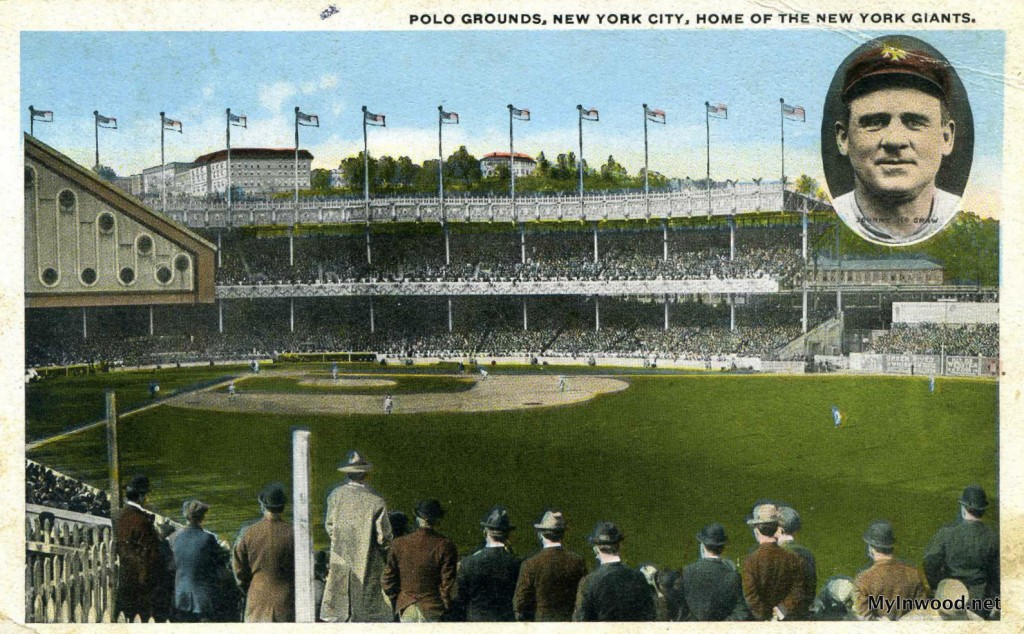

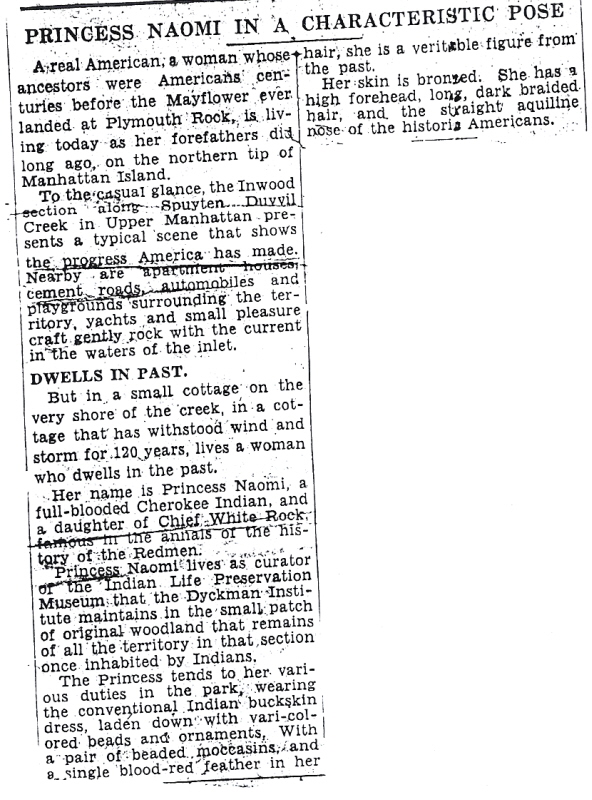

Mr. Wagner himself was riding that train. Webster Wagner, of Palatine Bridge, N.Y. (some fifty-five miles west of Albany). Inventor of the sleeping car, president of the Wagner Company, five times elected to the State Senate, and an influential member of its railroad committee.

![Webster Wagner, Source: Memorial of Webster Wagner, By L. D. Wells.]()

Webster Wagner, Source: Memorial of Webster Wagner, By L. D. Wells.

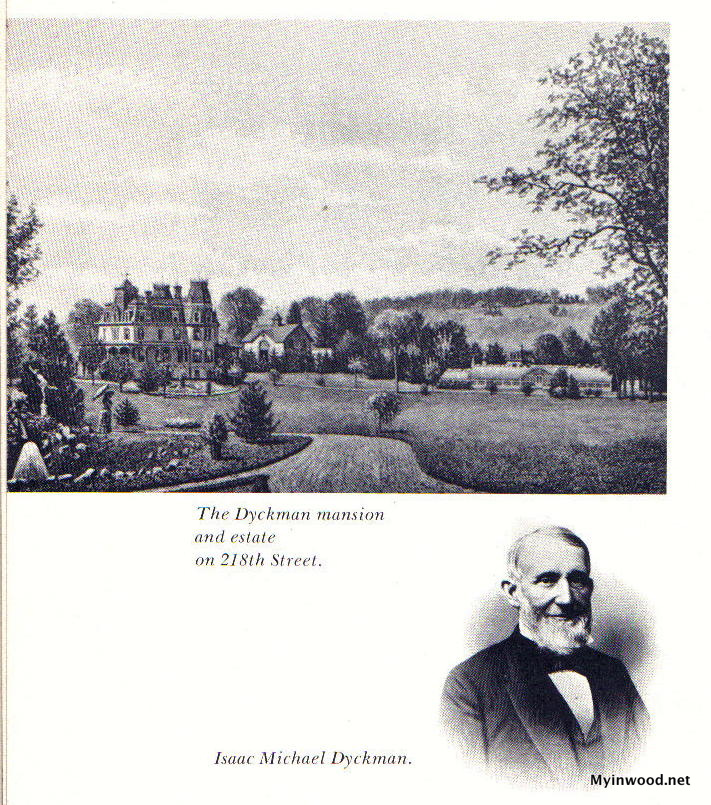

Mr. Wagner was sixty-four. He was tall and broad-shouldered, with a high forehead and blue eyes, and possessing rare vigor for a man of his age, his young son-in-law, Jay Taylor, was riding the same train as parlor-car conductor in charge of the Wagner rolling stock.

The newspapers that day were filled with rumors of a proposed merger between the Wagner Company, capitalized at five million dollars, and the Pullman Company, capitalized at ten million, which would soon be twelve and a half million. Such a combination would monopolize the field, revolutionize railway travel, and bring immense revenue to the stockholders of both concerns. It was expected to be the crowning triumph of Webster Wagner’s long and useful career.

![Stock certificate signed by Webster Wagner.]()

Stock certificate signed by Webster Wagner.

Newspaper reporters were trying to get a statement from Mr. Wagner; but, like the good politician that he was, he shook their hands with a genial smile—and talked about other subjects. As the Chicago Express rumbled through the deepening shadows of the late afternoon, winding the snow-covered banks of the Hudson, he passed around cigars to the political news-hounds and told his life story.

Mr. Wagner revealed that he was born at Palatine Bridge on the second of October, 1817, became interested in transportation at an early age, and was apprenticed to his brother James as a wagon builder. Later the two brothers went into partnership, but Webster soon decided there was more of a future in railroading, so he reassigned and got a job as station attendant at Palatine Bridge.

He held that job from 1843 to 1860. During that time he watched the long through trains of comfortless cars go by his station, and one day he stumbled upon the idea that brought him fame and fortune.

“I had never thought of the sleeping car,” Mr. Wagner admitted to the reporters, ”until I saw one of a very clumsy pattern built by a man living near Palatine Bridge. The man had no capital, no capacity, and not much inventive genius. I saw right away that his idea was good, but had to be developed.”

![William H. Vanderbilt trading card from the 1880's.]()

William H. Vanderbilt trading card from the 1880′s.

“I hadn’t much capital, either, but I applied to William H. Vanderbilt for permission to use an old coach to illustrate my notion of what a sleeping-car should be. I knew that the Hudson River Railroad was sharing a large amount of business with the night boats that it should have for itself. Men who needed all the time they could get begrudged the five or six hours lost in traveling between Albany and New York by boat. It seemed to me that much time could be saved by providing accommodations for merchants and others who would be glad to sleep while they traveled rapidly.”

He broke off abruptly, opened the window and peered out. The snow had stopped falling. A tiny station rushed by in the gathering twilight.

“The air feels good!” he exclaimed, and closed the window. “It was quite a problem for me to get the right ventilation in those cars. Oh, yes, as I was saying, my request for an old car was granted, and I went to work to fit it up with berths. It took me months to finish that car. Even then it had to be seen and approved by Commodore Vanderbilt before it could be used on the road. I urged his son, William H., to persuade the old man to look at my car. At first the Commodore ignored my request, but finally consented.”

“It was a critical Sunday morning in 1858 when old Vanderbilt and his son were to visit the Thirtieth Street depot in New York to look at my new-fangled contraption. Before they arrived I walked through the car a dozen or more times to see that everything was all right. After the Commodore had made his inspection he asked:

“’How many have you got of these things?’

“’There is only one,’ I told him.

“’Go ahead!’ he said. ‘Build more! It’s a devilish good thing, and you can’t have too many of them.’

![Interior of Wagner Palace Car, 1875. Interior of Wagner Palace car, 1875.]()

Interior of Wagner Palace Car, 1875.

“I realized then that my fortune was made,” Senator Wagner continued. “With my brother’s help four cars were built at a cost of thirty-two hundred dollars each, and they began running on the first of September, 1868. The first car had a single tier of berths, and the bedding had to be packed away in a closet at one end of the car, thus occupying valuable space. Too much, in fact. The one tier of berths was not profitable enough, so another was installed. Thus the modern sleeping car came to be.”

“What did you do about ventilation?” one of the reporters reminded the inventor.

“Oh, yes,” was the reply. “At first the ventilation system was found to be imperfect. The upper berths were too close, as the roof was flat. To overcome that objection I devised and applied the pitched roof, much higher than that of the old cars; thus securing ventilation and eventually the swinging upper berth which was adopted later and is in use today.”

Incidentally, the invention of the elevated roof proved so useful that it was applied not only to sleepers, but also to day coaches. On August 20th, 1867, Mr. Wagner put into operation his first drawing-room car for day travel. He made several trips abroad to study the English, French and Swiss passenger cars, survived two or three wrecks, and finally, in 1882, was looking forward to a merger with the rival interests of George M. Pullman. (Neither Wagner nor Pullman invented the first sleeping-car. Back in 1843 the Erie Railroad had 2 sleepers, known as “diamond cars” after the shape of their windows, built by John Stephenson. Even before that in 1837, the Cumberland Valley (P.R.R.) had a sleeper, the “Chambersburg,” with 12 berths in 3 tiers but no bedding.)

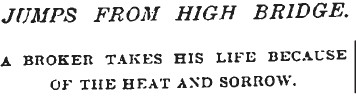

But Senator Wagner did not live to see the merger consummated. And all because of that hilarious group of politicians who were riding in his drawing-room cars from Albany to New York on Friday the 13th. At least, that’s what the train crew maintained in the investigations that followed, although no one came forward to name the guilty person.

Everybody agreed that there was quite a bit of drinking among the passengers that afternoon on the Chicago Express, and even two or three of the porters showed signs of intoxication. As Conductor George Hanford testified later:

“We had a lively party on board. All through the cars they were passing bottles, drinking freely, smashing hats, and signing songs. Apparently they were sober when they boarded the train in Albany, but many became drunk after the train started. I had no control over them. Someone, I don’t know who, pulled the rope connecting with the air brakes, and the train came to a standstill, to enable the engineer to pump out the air.”

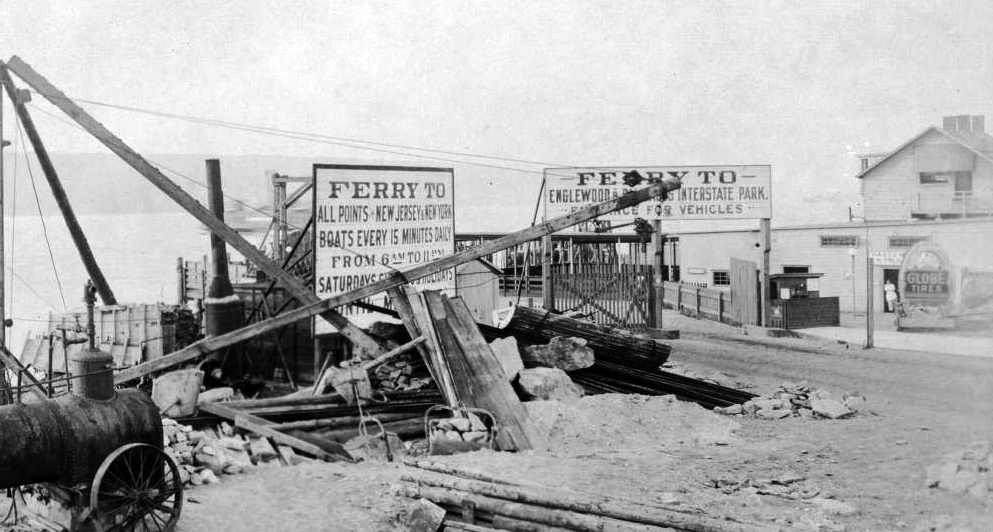

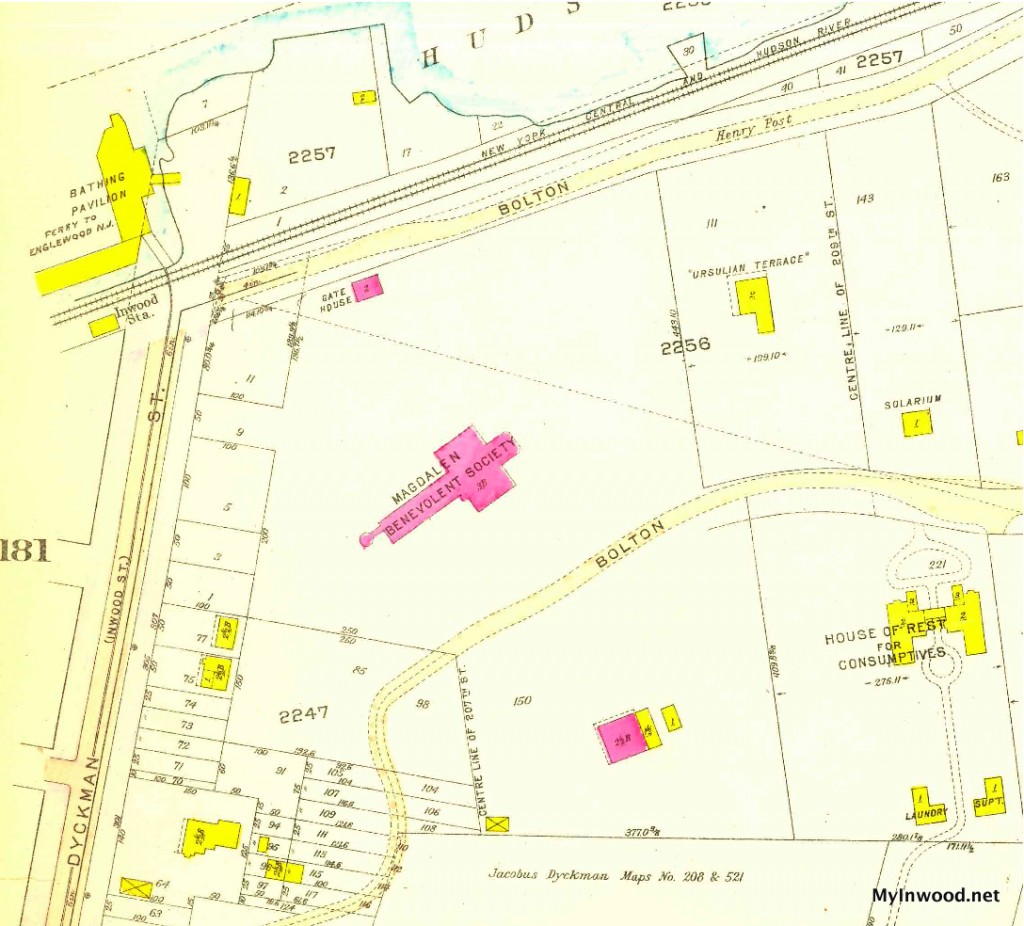

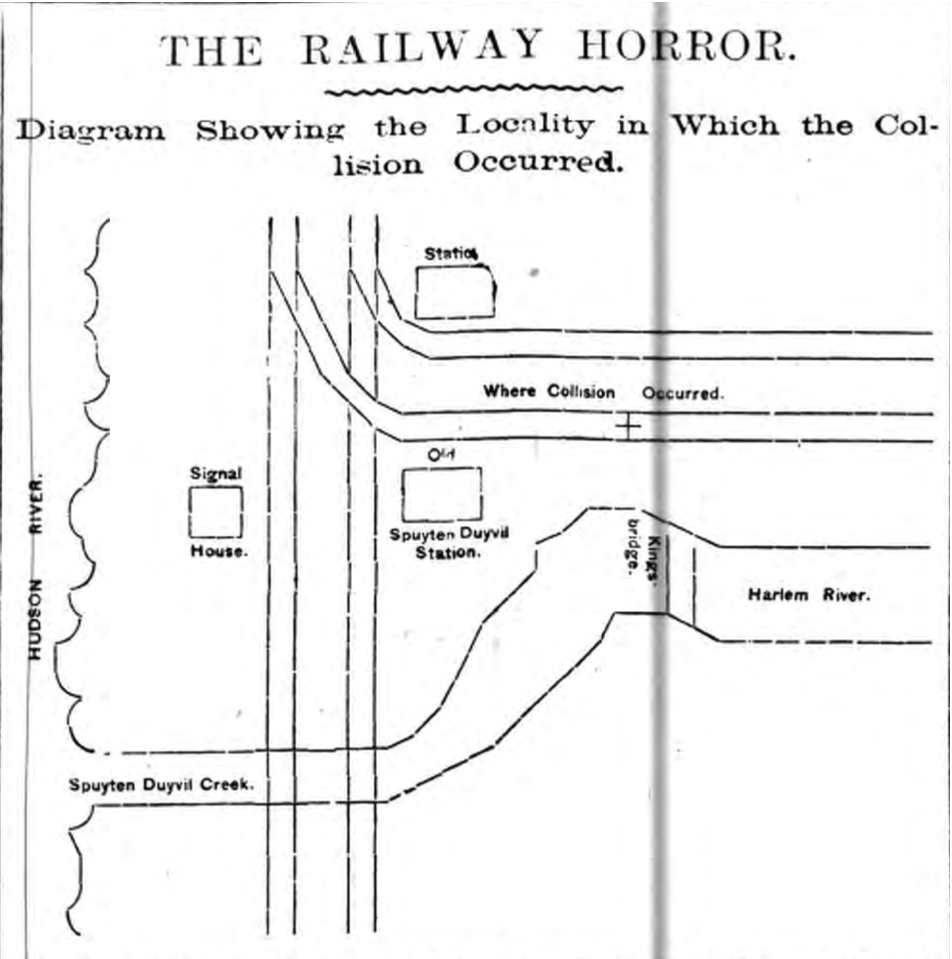

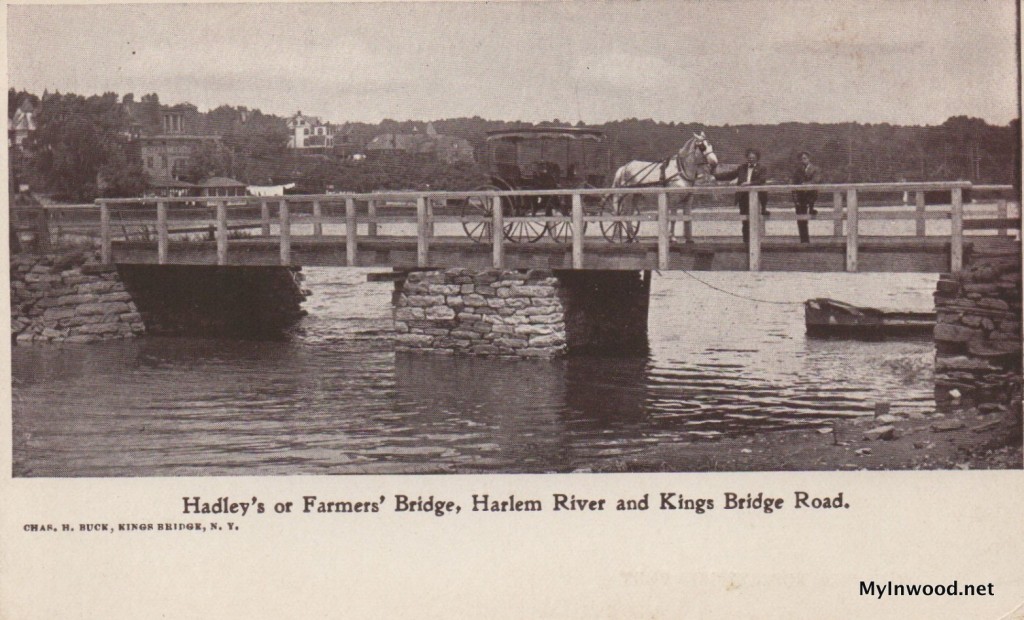

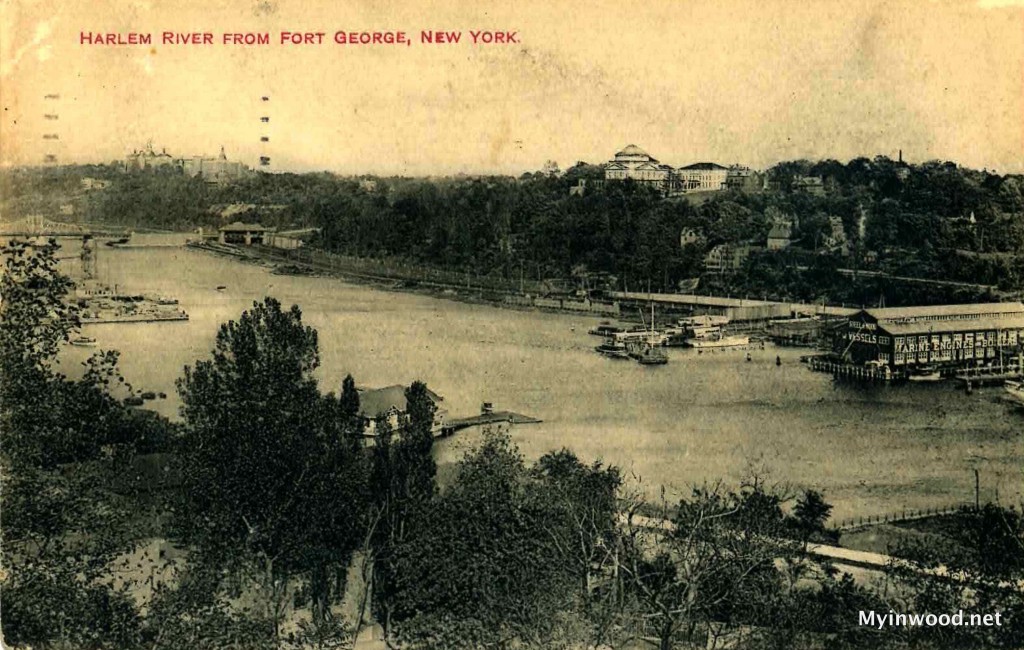

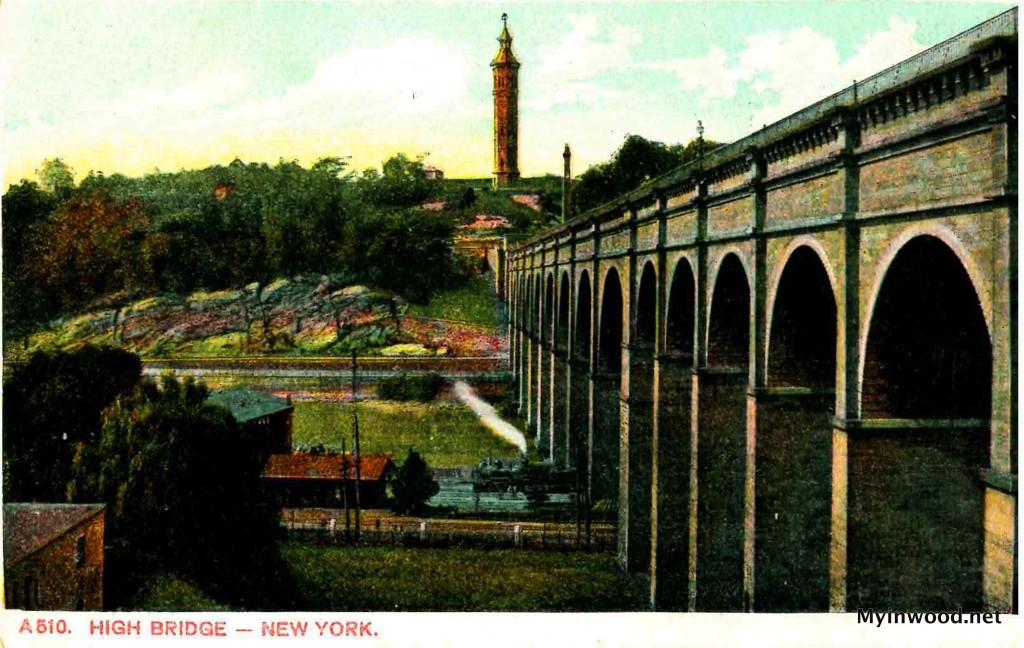

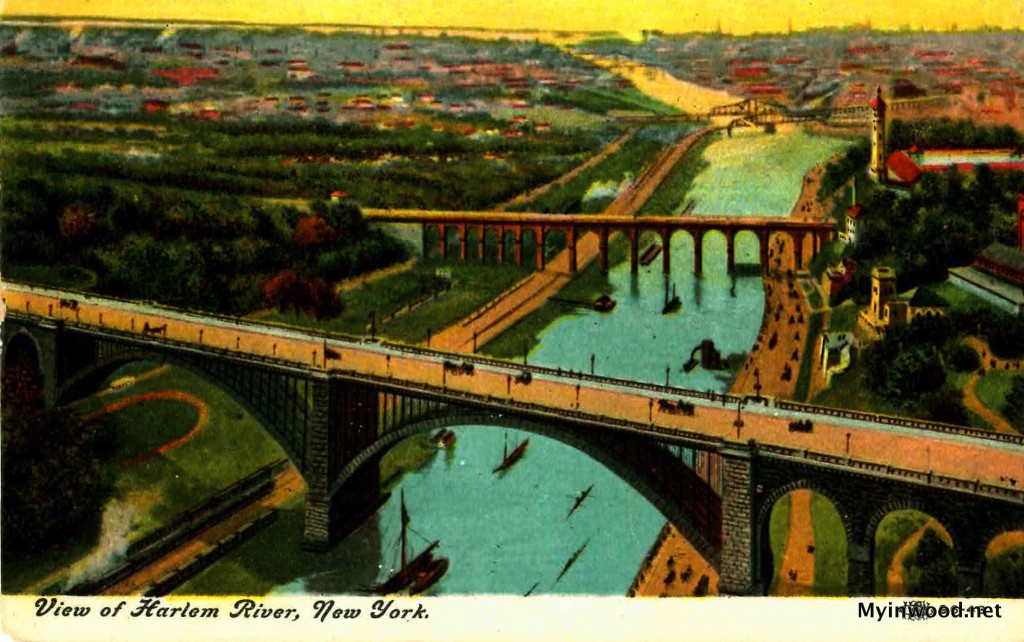

If pulling the rope was intended to be a joke, it proved to be a ghastly one. The train had stopped a little to the north of Spuyten Duyvil, on the outskirts of New York City. At that point there was a deep cut through a ledge that obstructed a view of the station. On one side rose rocks and high ground. The other side sloped down toward the Hudson River.

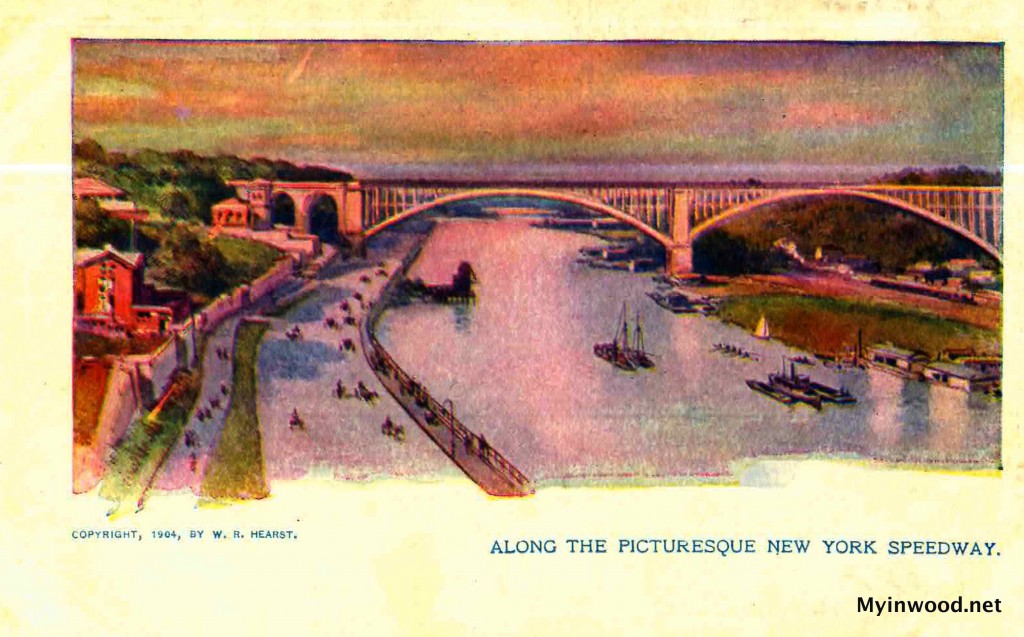

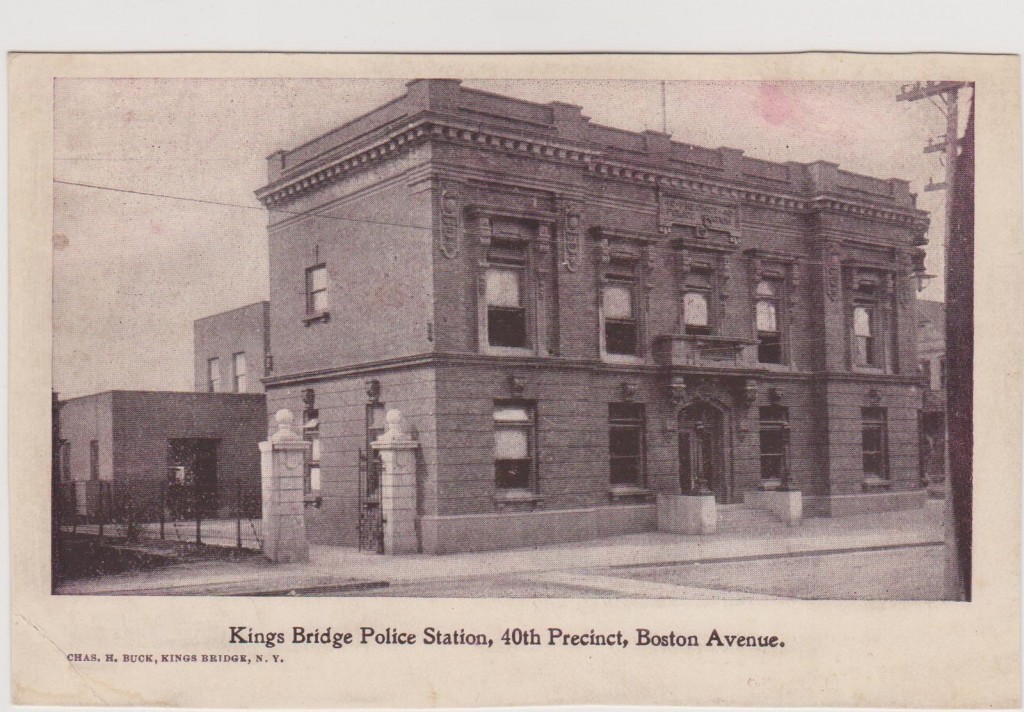

![Map from New York Herald, January 14, 1882.]()

Map from New York Herald, January 14, 1882.

Just before entering the cut a southbound train had to round a long curve, and see what was around that curve ahead of them. Previously the N.Y.C. & H.R. had kept flagmen on duty at both ends of the cut, Bill McLaughlin and Richard Griffon, paying them each about thirty dollars a month, but in a wave of economy they had discharged McLaughlin, leaving the dangerous stretch of track insufficiently guarded at the north.

At the moment the express cam to a sudden stop, Senator Wagner was talking to some of his political companions in the Empire, the second car from the rear. One of them was saying:

“I’ve got a couple of friends here who want to get passes from you.”

Nobody knows whether or not the inventor had a presentiment of tragedy on that occasion, but he certainly betrayed uneasiness over the unscheduled stop. He rose and remarked:

“Well, gentlemen, I think I’ll take a look through the train. These confounded railroads have a passion for smashing up my best cars.”

Mr. Wagner left the Empire and hurried back into the end car, the Idlewild. That was about 7 p.m. It was the last time he was seen alive.

Edward Stanford, engineer on the first locomotive, who had been employed on the New York Central for twenty-five years, made several attempts to start his train, but only succeeded in breaking the drawbar connecting the two engines.

The second engineer on the doubleheading express, Archibald Buchanan, who had eighteen years of engine service on that road, said later that he had seventy-five pounds of air on, and it had dropped at once to forty when somebody back on the cars pulled that cord, and he had tried to relieve the brakes by pumping them off. Recharging an air cylinder, he pointed out, took about fifteen minutes.

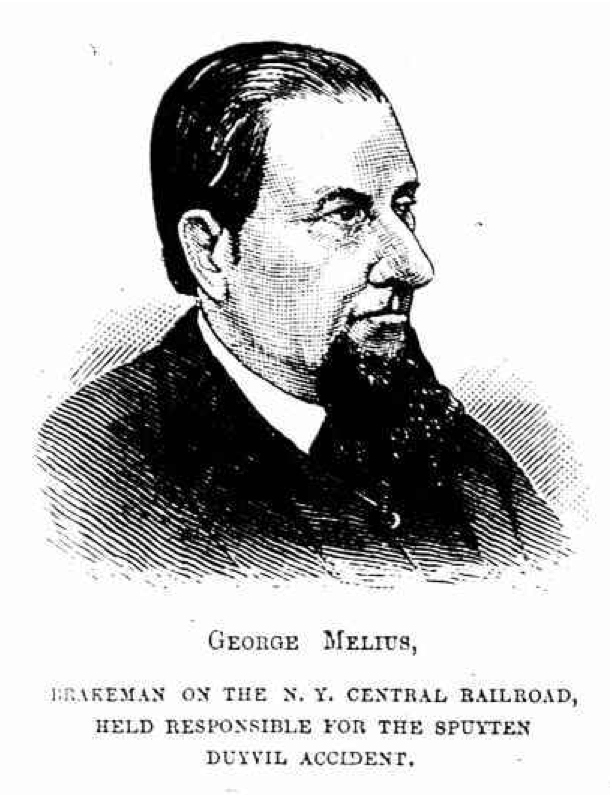

Meanwhile, George Melius, the hind brakeman, swung into action. This was his story:

“A minute or two after our train stopped I got my lamps, white and red, and walked back to protect the rear. I stood behind my train about two minutes, and then started back around the curve about six or seven car lengths behind my train. It took me about five minutes to walk that distance” – at the investigation later he was made to walk the same distance, which took only two minutes – “and I stood there perhaps two or three minutes.”

“I waited there because I considered the distance sufficient to stop any train. While I was on duty at that point, the Tarrytown local came in sight, seven or eight car lengths from where I stood. Instantly I started waving my red lantern across the track. I think there was time enough to stop the train, even though I judged she was making about forty miles an hour.”

His brother, who was a conductor on the Poughkeepsie train, advised Brakeman Melius to modify that speed estimate in telling his story to the coroner’s jury – “because,” said Conductor Melius, “the Tarrytown local had just stopped at the Spuyten Duyvil depot and could not possibly have picked up so much speed in that distance.” So George modified his story for the official investigation.

At 6:40 p.m. the southbound local had left Tarrytown, N.Y., fourteen miles away, with Frank Burr at the throttle and Patrick Quinn wielding the scoop. Both were men of years experience in engine service on the N.Y.C.

“We were five minutes behind time when we pulled out of Tarrytown,” Burr explained, “because we had waited for the Chicago Express to pass us there. The express went by at 6:15 at high speed, evidently making up for lost time. We stopped at Spuyten Duyvil depot at 7:04. We were then thirteen minutes behind the express.”

The number “thirteen” seems to run like a theme song through the history of this occurrence. It was Friday the 13th, there were thirteen cars on the express, and the local was running thirteen minutes behind the express.

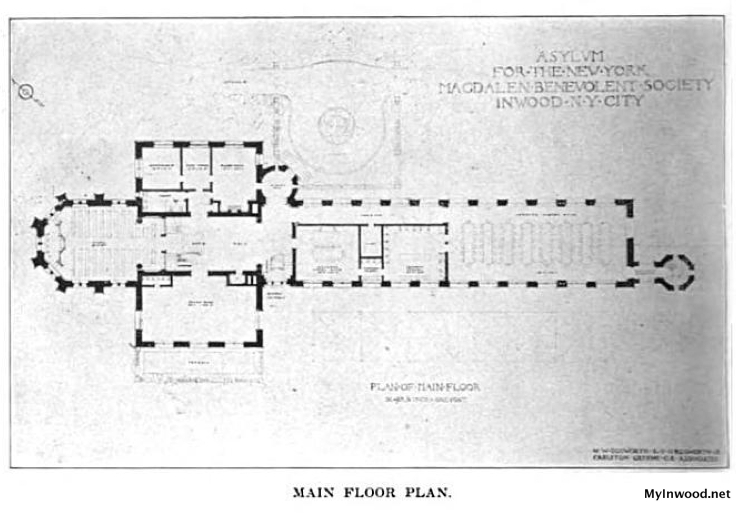

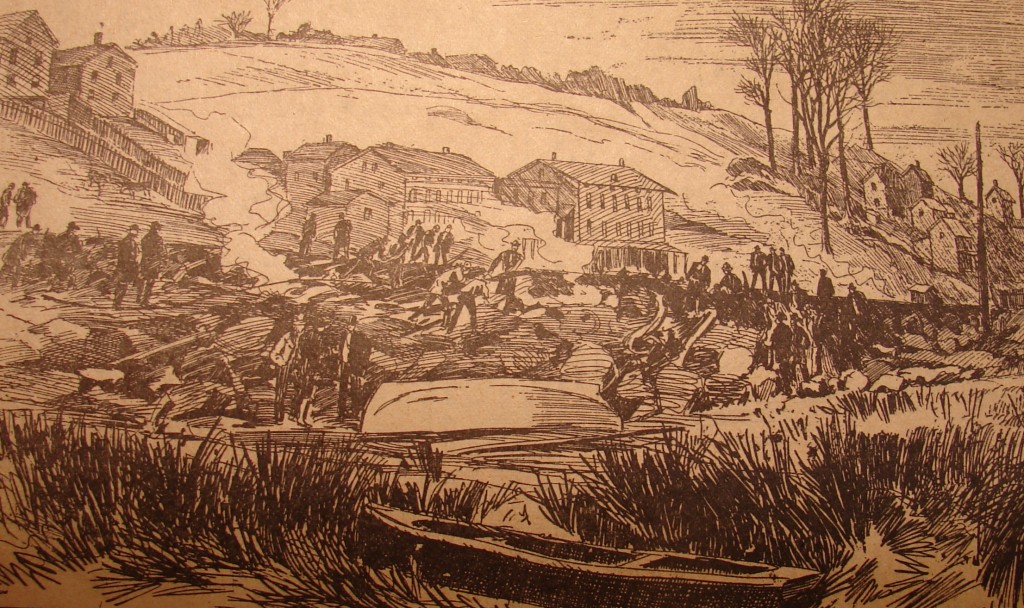

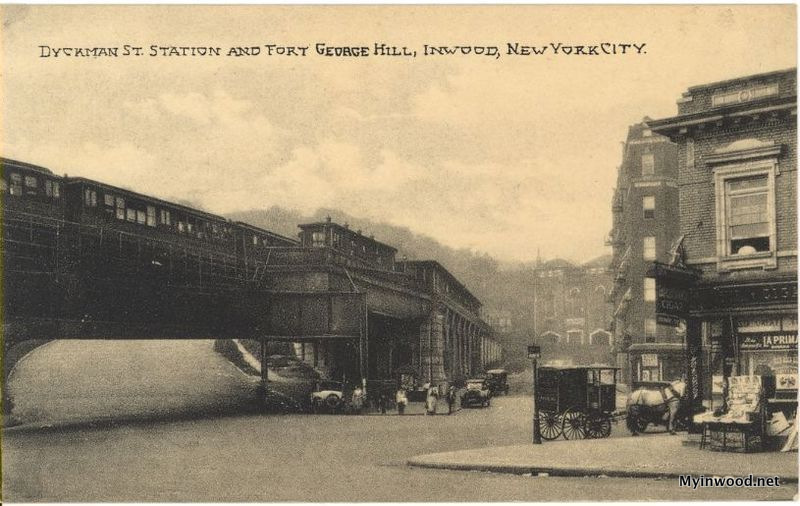

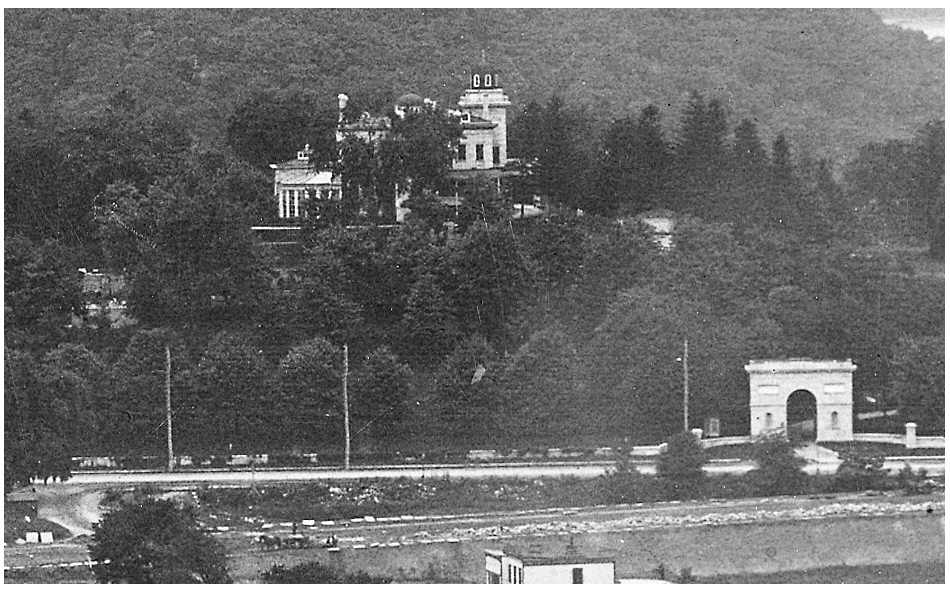

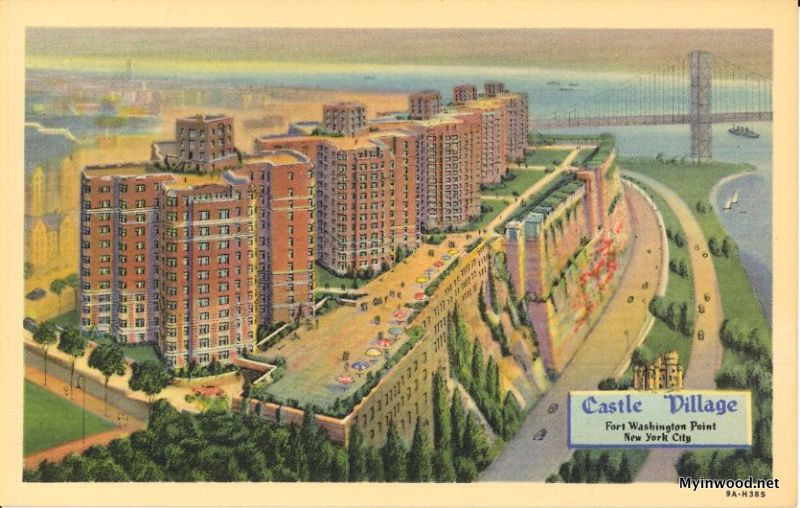

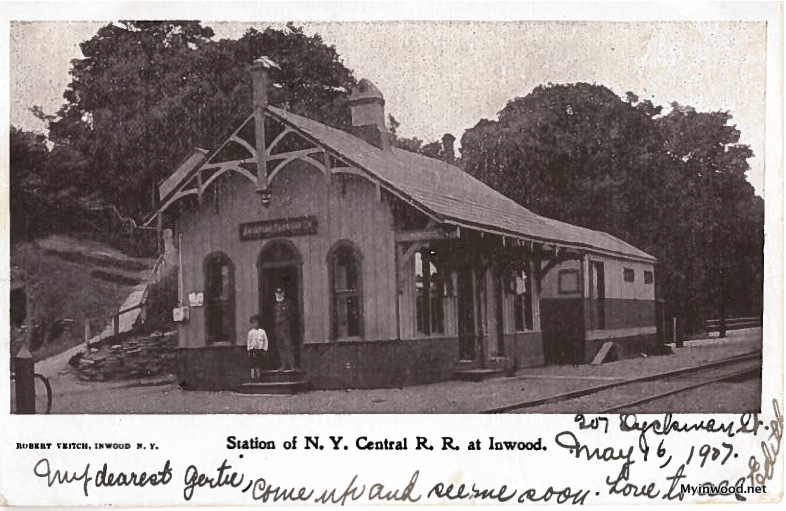

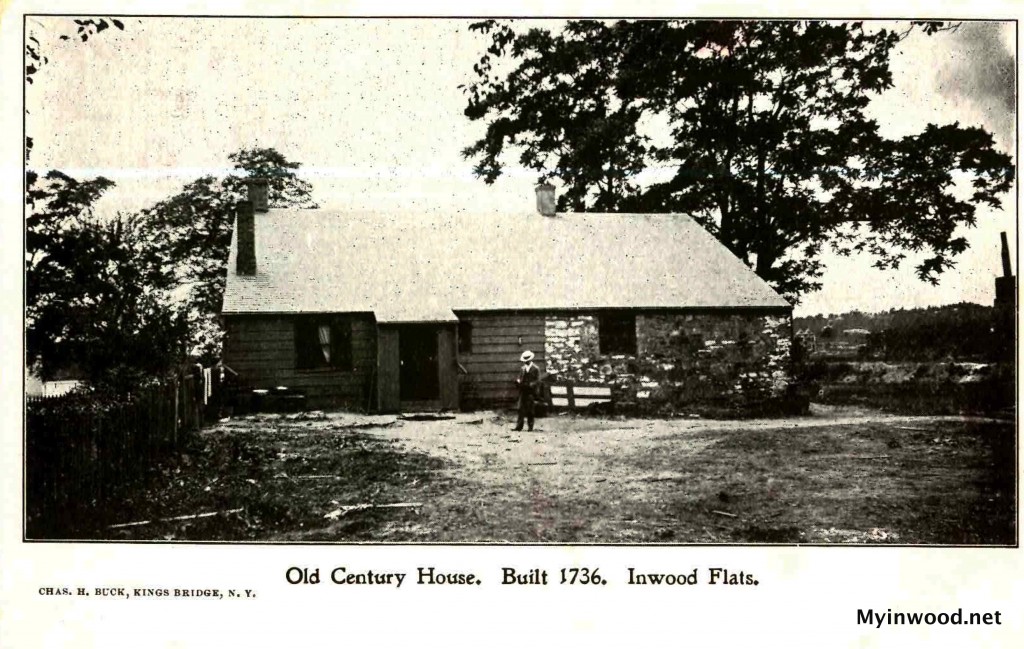

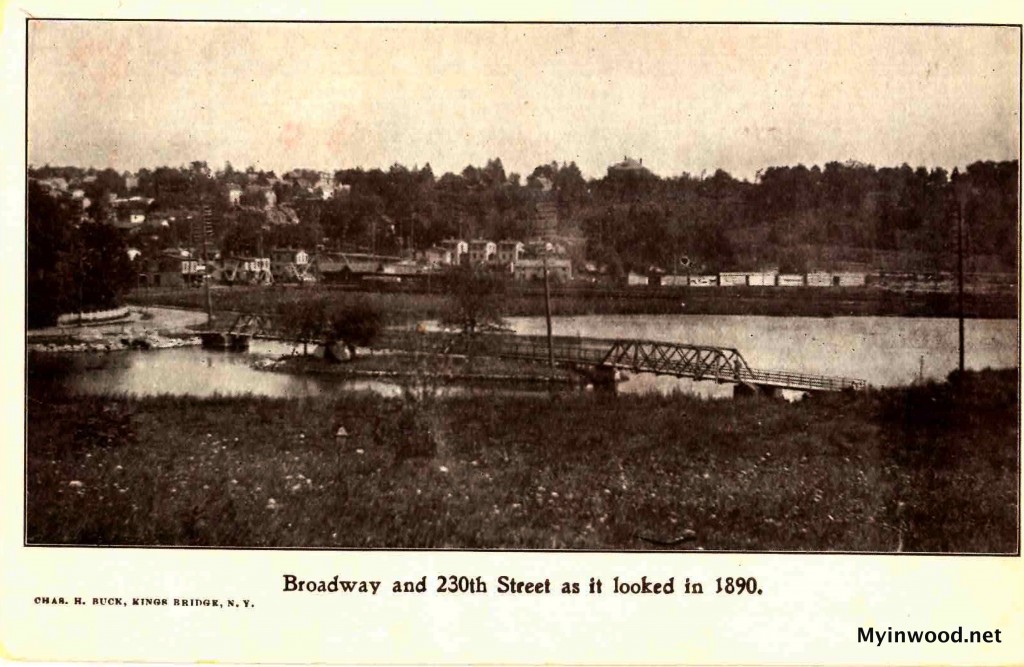

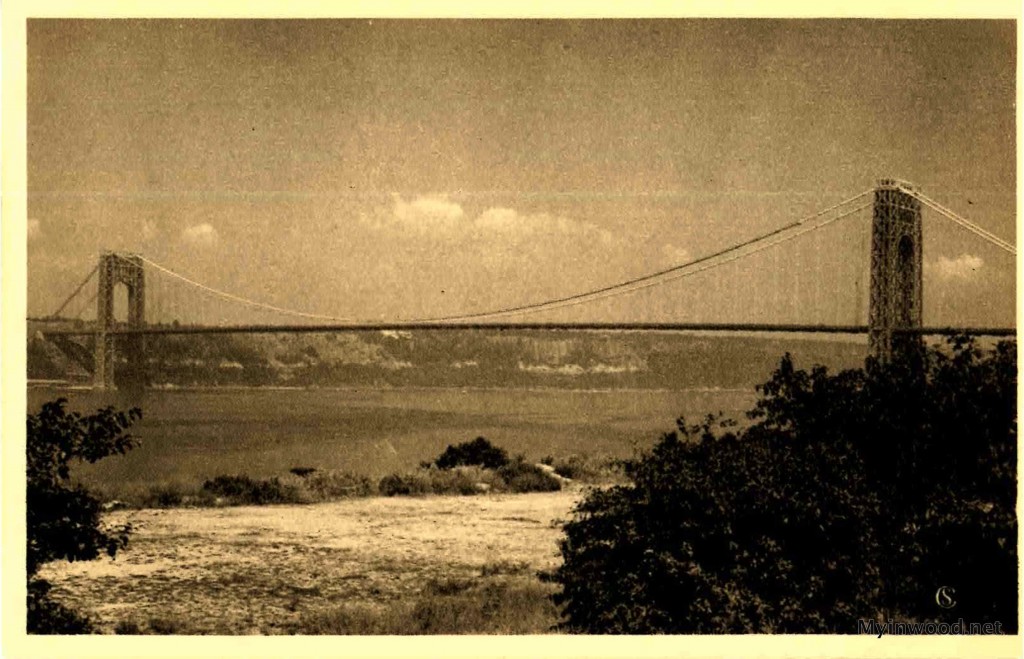

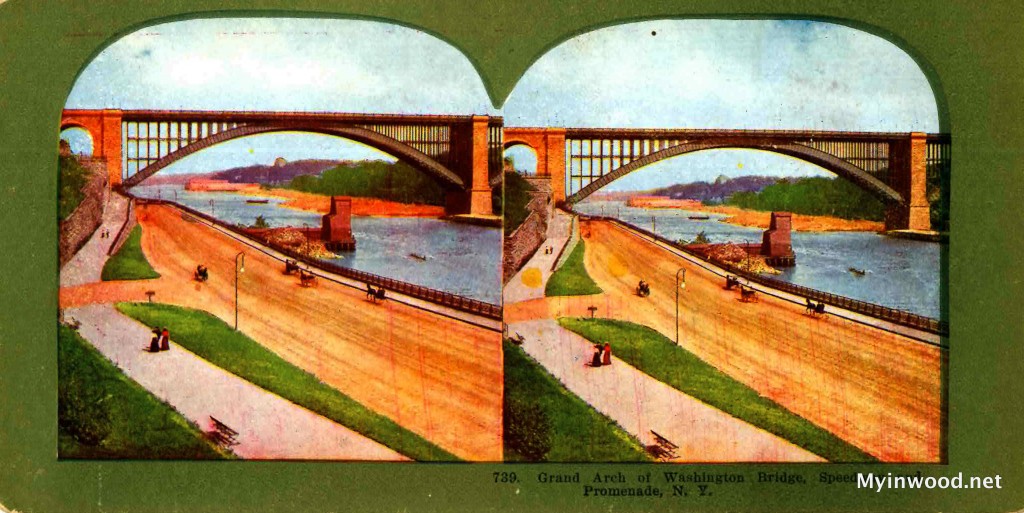

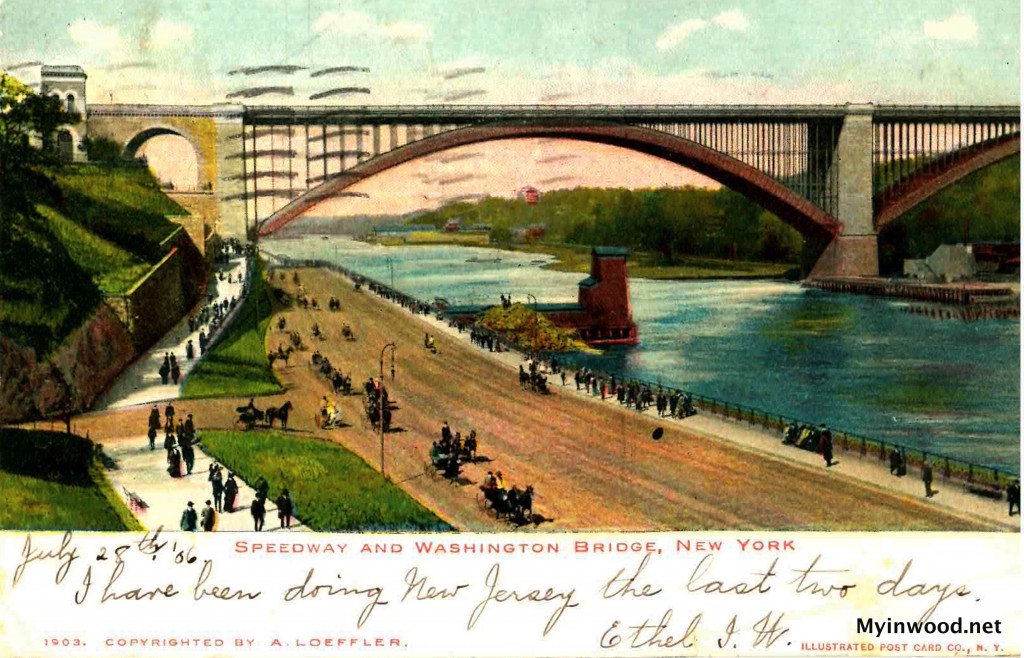

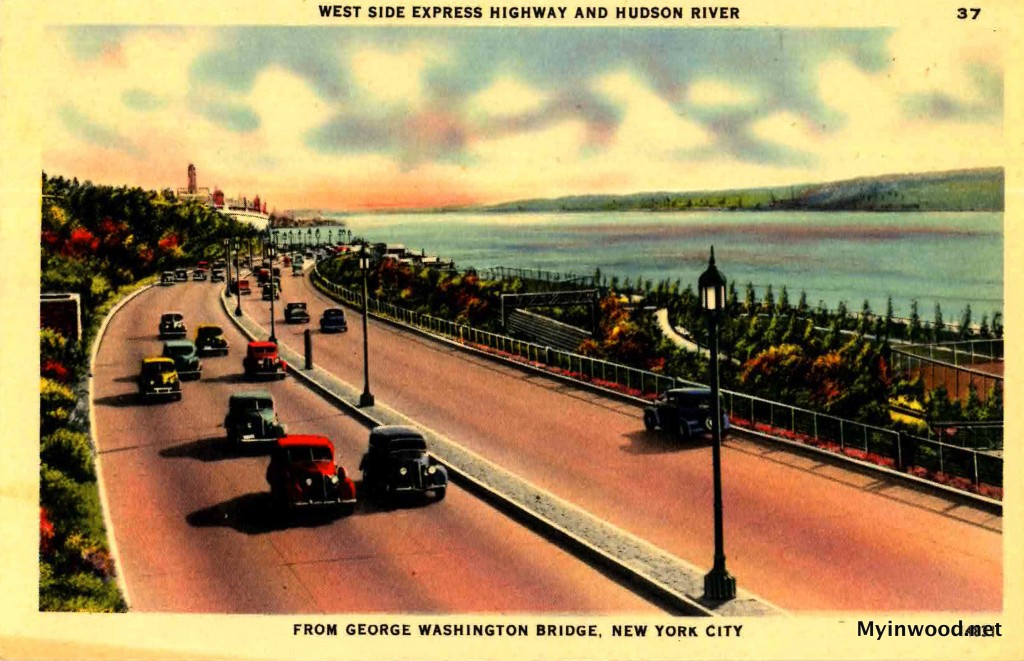

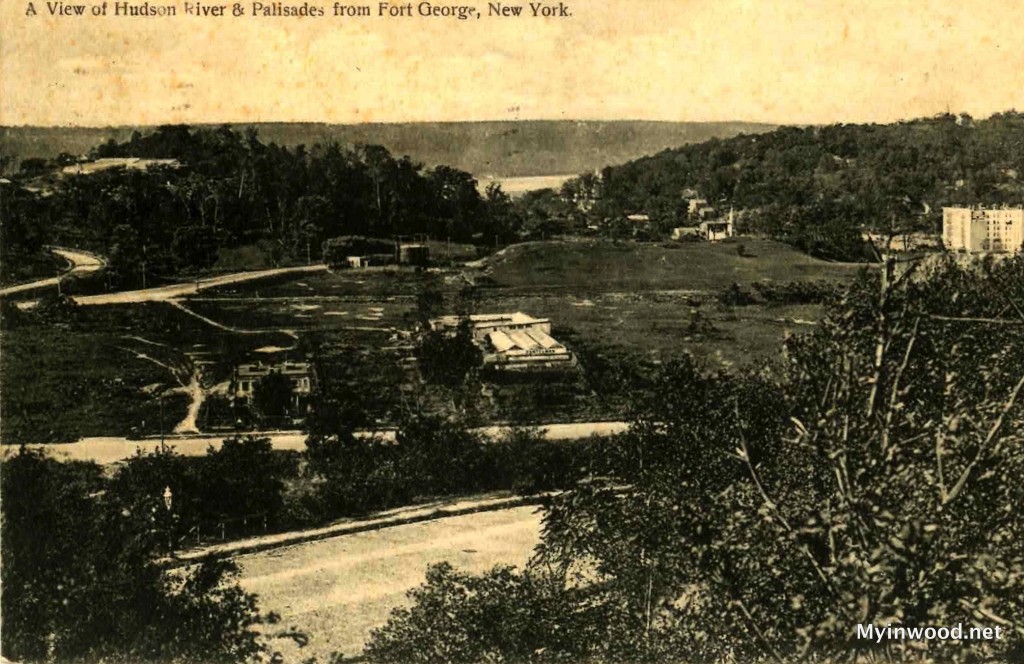

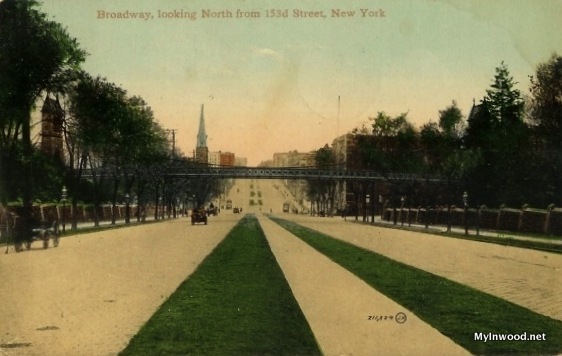

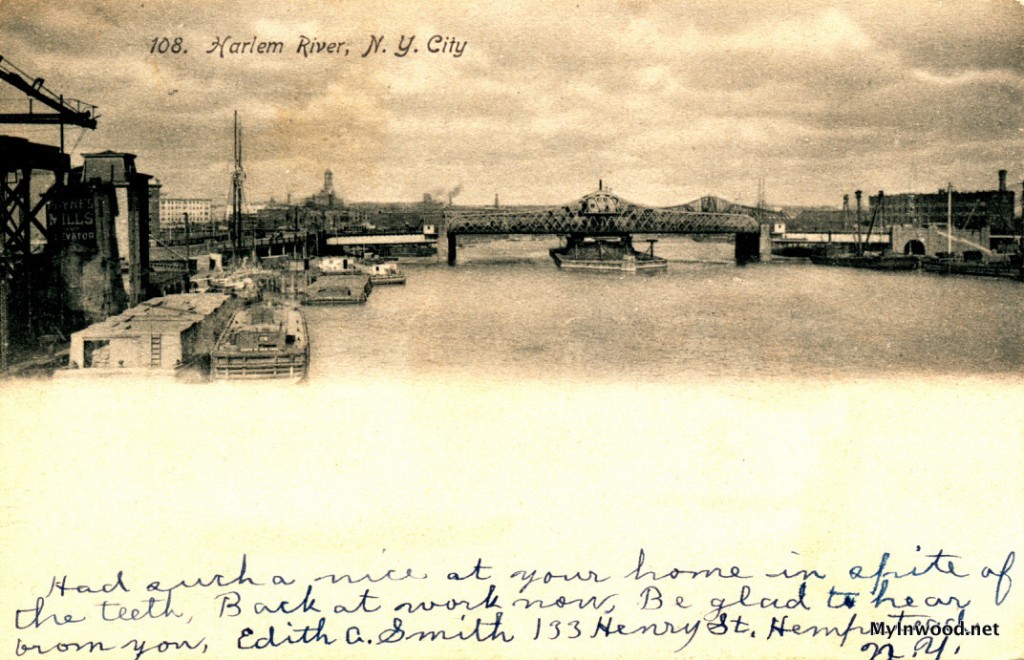

!["The northern boundary of Manhattan Island, N.Y. City, as it looked in 1882. This section today is served by two Metropolitan subway-elevated systems. At the upper left is the New York Central main line, which parallels the Hudson River to Albany." Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.]()

“The northern boundary of Manhattan Island, N.Y. City, as it looked in 1882. This section today is served by two Metropolitan subway-elevated systems. At the upper left is the New York Central main line, which parallels the Hudson River to Albany.” Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.

“After leaving Spuyten Duyvil,” said Engineer Burr, “we entered the cut at the rate of eighteen or twenty miles per hour. There was no danger signal or warning of any kind in the cut. And, I might add, Kilcullen’s Hotel, standing close to the right-of-way, completely shut off our view of the curving track until we were almost on top of the stalled train.”

“We passed out of the cut into the curve – I was looking ahead at the time – when I saw a flagman (Melius) with red and white signals in his hands. He was swinging the red across the down track, upon which we were. At the same time I saw the rear of the express before me.”

“When I first noticed the red light, the flagman was standing not more than two car lengths ahead of me, and the train was not more than thirty-five feet beyond the flagman. Altogether I was not more than three and a half car lengths behind the express when I first sighted her.”

“I put on the air brakes at once, reversed the engine, pulled the throttle wide open, blew the whistle, and did all in my power to stop. But a collision was inevitable. I remained at my post until the engine finally plowed into the rear of the express and stopped there. Then I got out and did what I could do to help with the work of rescue.”

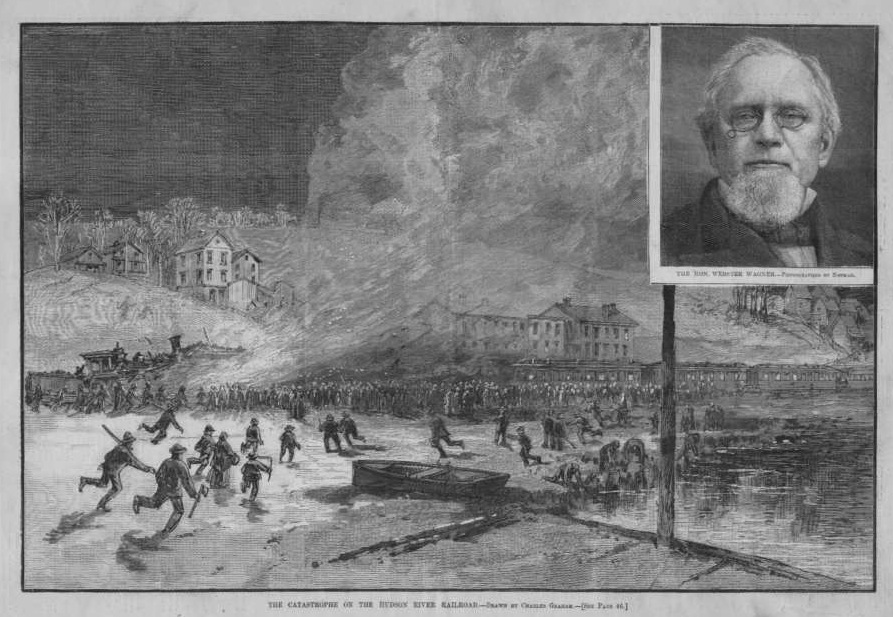

The locomotive of the Tarrytown local was only slightly damaged. Her overhauling was estimated later to be not more than a fifty-dollar job. She was embedded in the parlor car Idlewild. Her headlight, broken but still shining, had pushed its way a dozen feet within the luxurious car, casting a weird glare upon the terrified passengers.

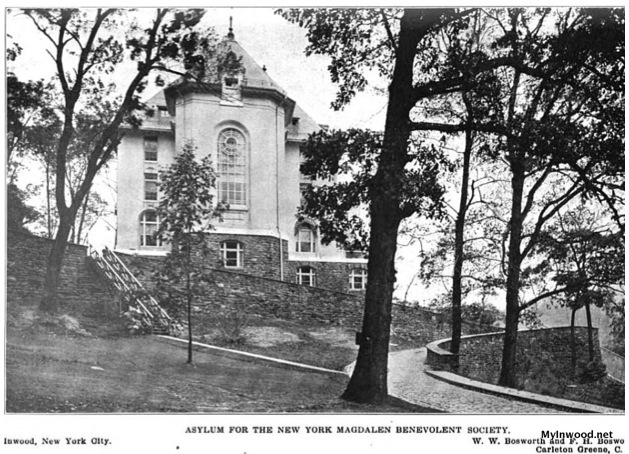

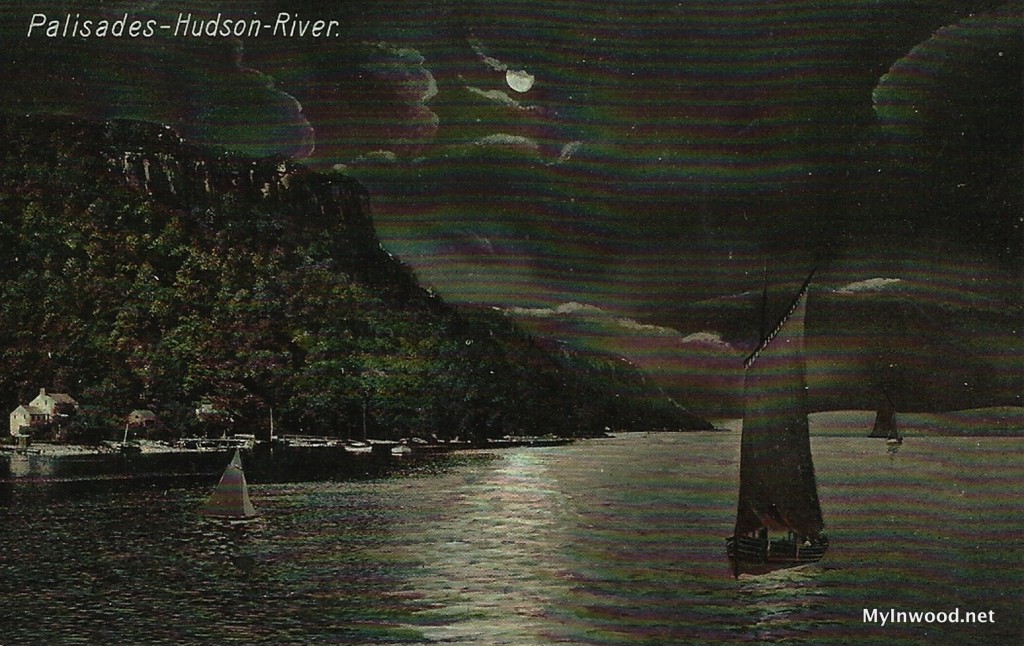

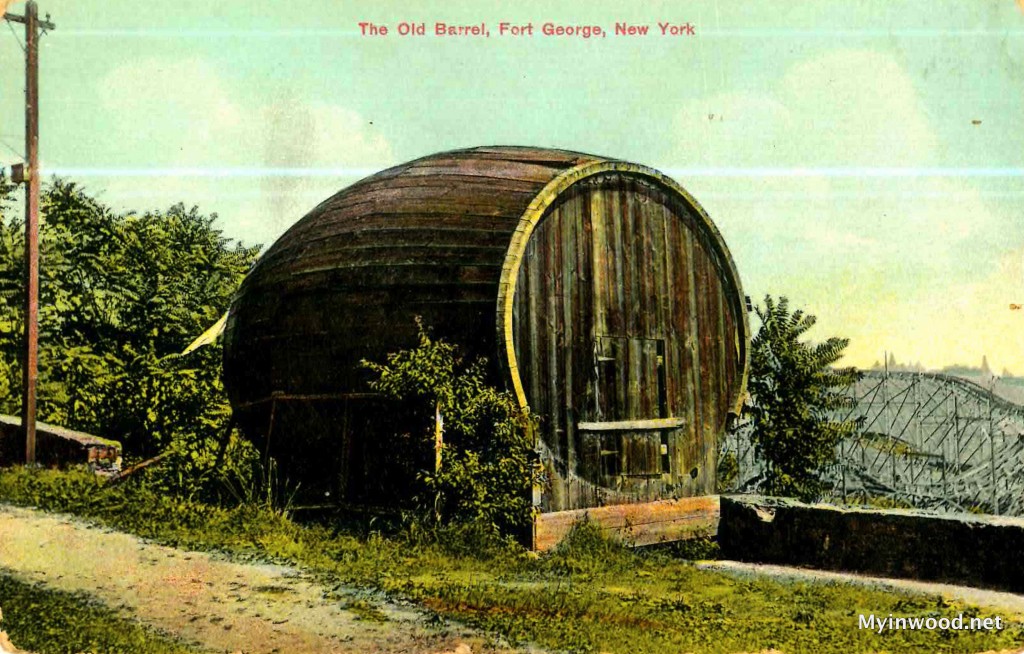

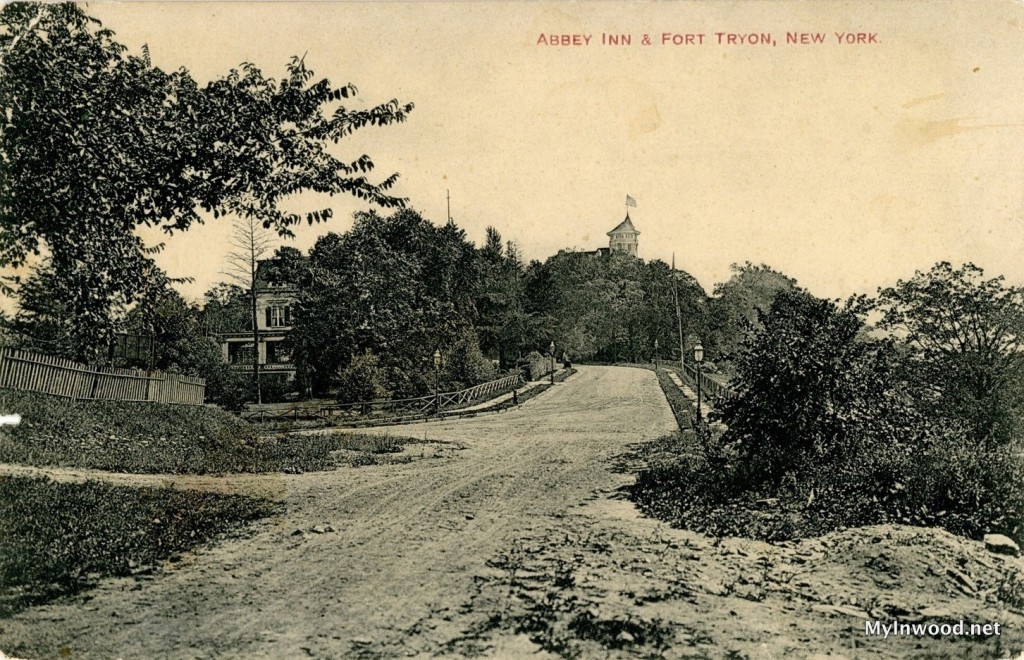

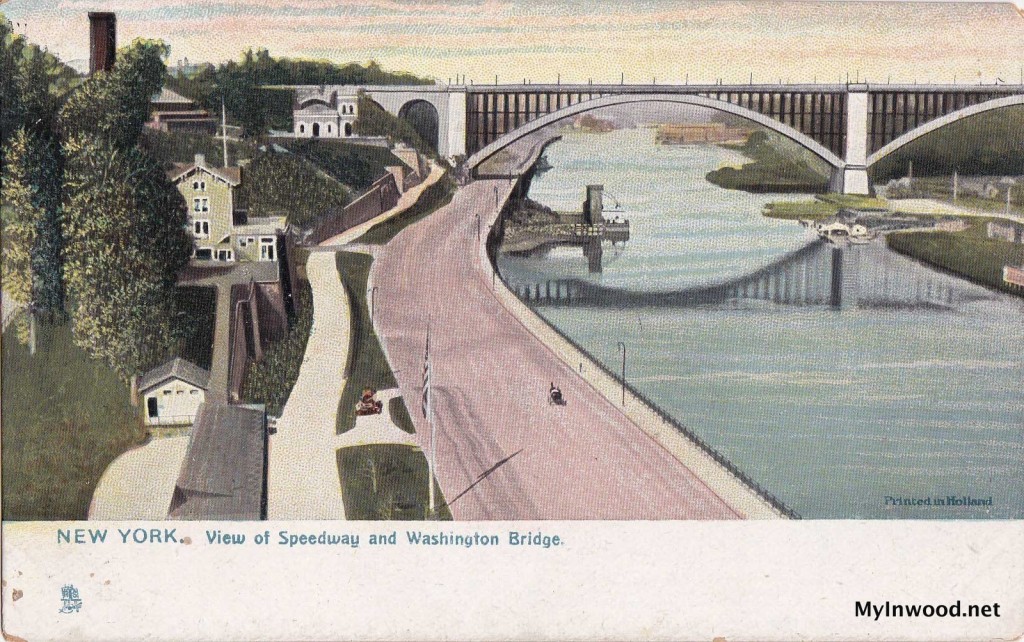

!["Scene of Spuyten Duyvil wreck, looking toward the northwest, just after the railroad tracks had been cleared. In the foreground is the creek, which marked the boundary line between Spuyten Duyvil and Manhattan. In the center are shown Kilcullen's Hotel and Saloon, to which the victims were taken." Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.]()

“Scene of Spuyten Duyvil wreck, looking toward the northwest, just after the railroad tracks had been cleared. In the foreground is the creek, which marked the boundary line between Spuyten Duyvil and Manhattan. In the center are shown Kilcullen’s Hotel and Saloon, to which the victims were taken.” Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.

The Idlewild, in its turn, had been partly telescoped into the car ahead, which was the Empire. It was not known then how many persons had been killed or injured, but the engine had a full head of steam and a boiler explosion was feared. An explosion under those circumstances would have added frightfully to the casualty list.

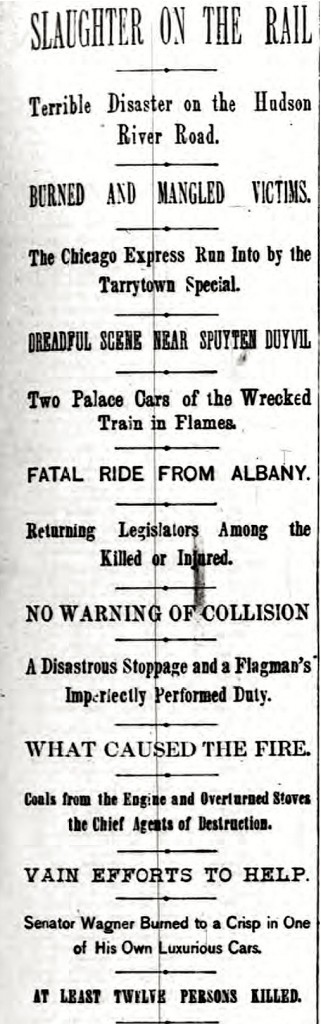

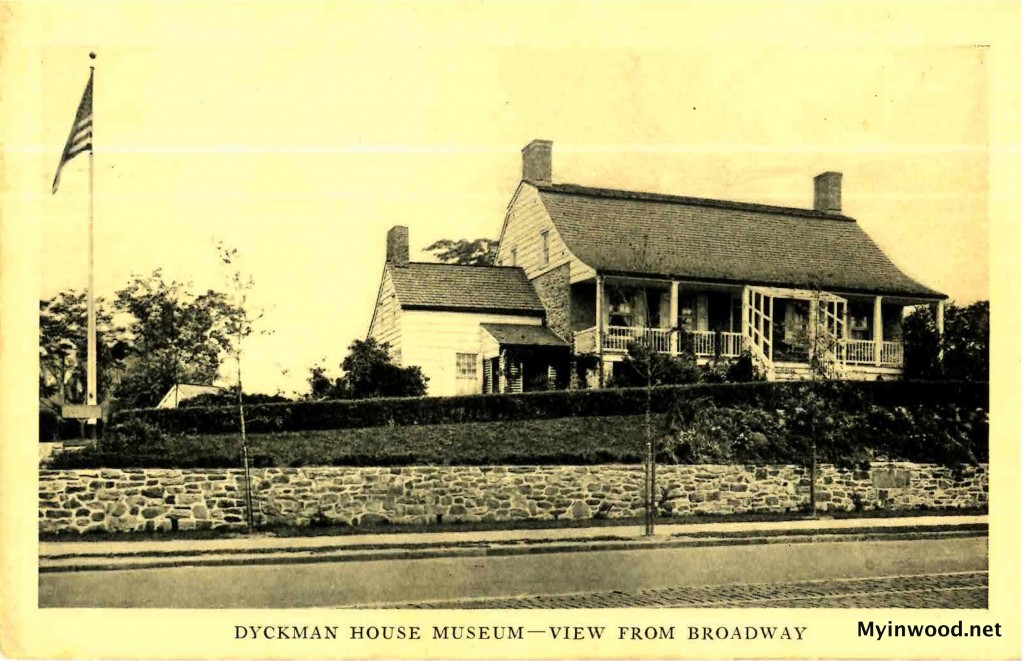

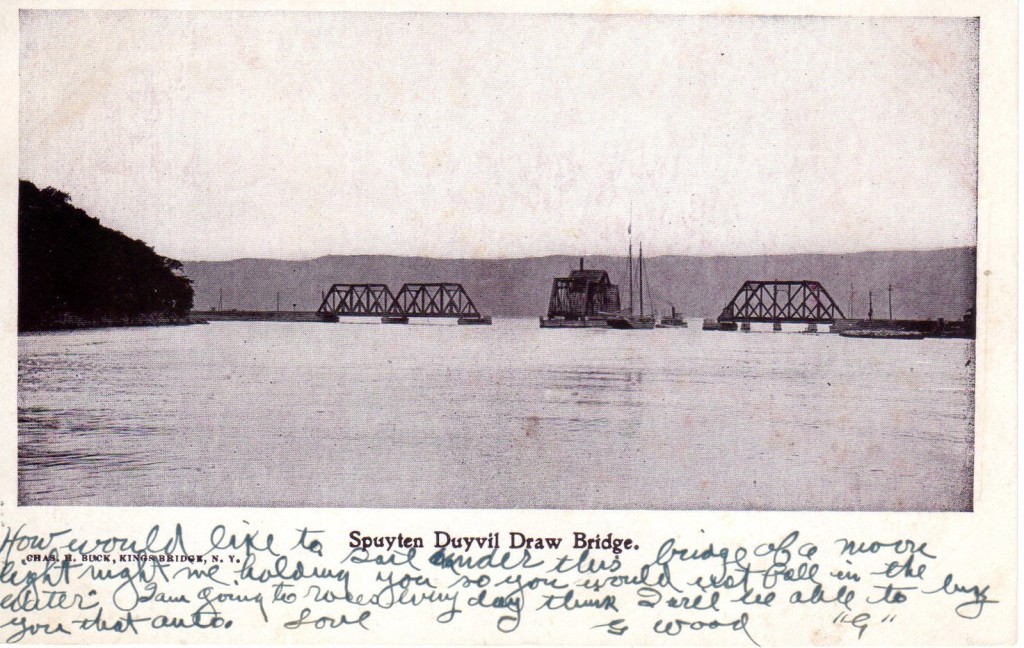

![Spuyten Duyvil train crash headline, New York Herald, January 14, 1882.]()

Spuyten Duyvil train crash headline, New York Herald, January 14, 1882.

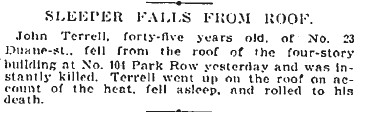

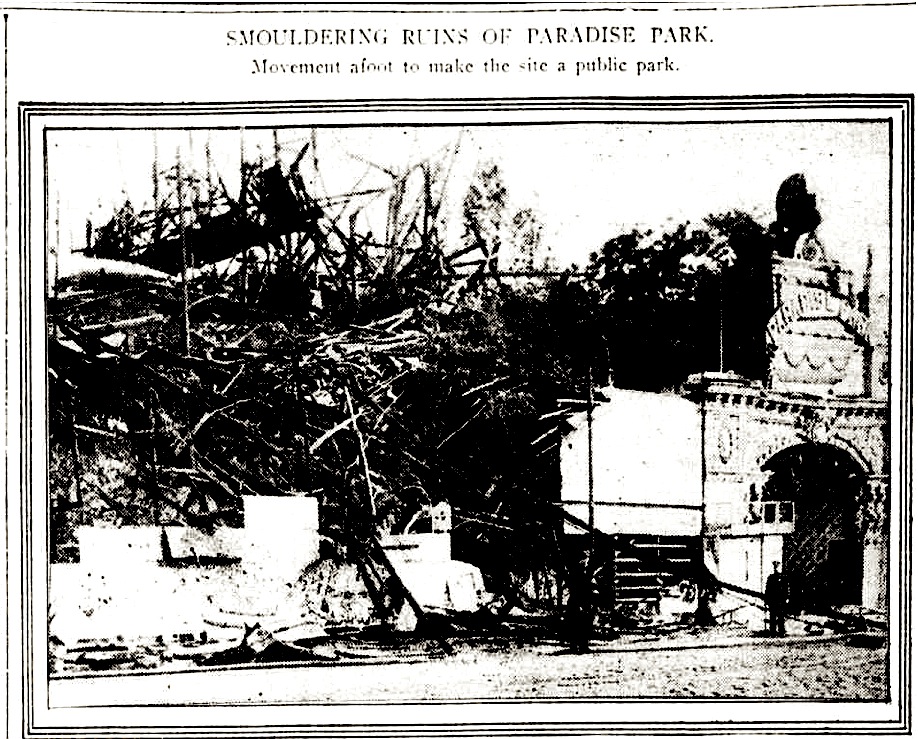

James Kilcullen, proprietor of the small saloon and hotel near by, had viewed the catastrophe from his doorway, and was one of the first to hasten to the rescue with a ladder, an ax, and a couple of water buckets. Said he:

“If you want to use a shutter or two to carry the victims on, don’t hesitate to tear them off my house.”

Survivors of the wreck who had managed to scramble out of the cars, aided by a number of husky fellows who hurried to the scene from near-by villages, formed a bucket brigade and threw water from the Hudson River onto the last two parlor-cars, which had caught fire almost immediately after the collision.

Engineer Burr was the first to recognize the damage of a boiler explosion. Seizing the fireman’s scoop from Patrick Quinn, he commenced piling great shovelfuls of snow into the furnace. Fortunately, although it was mid-winter, the weather was rather mild, and the snow was soft enough to work with.

Water carriers, who had been emptying their pails onto the flaming cars, followed Burr’s example and dashed them against the locomotive boiler instead. Eventually the fire in the firebox was quenched, and attention was turned once more to the Empire and the Idlewild, from which came the agonizing cries of victims who were slowly burning to death.

Conductor Hanford, of the express, noticed that the occasional pailfulls of water were doing very little to check the blaze. “For God’s sake, hurry!” he cried. “Throw snow onto the fire!”

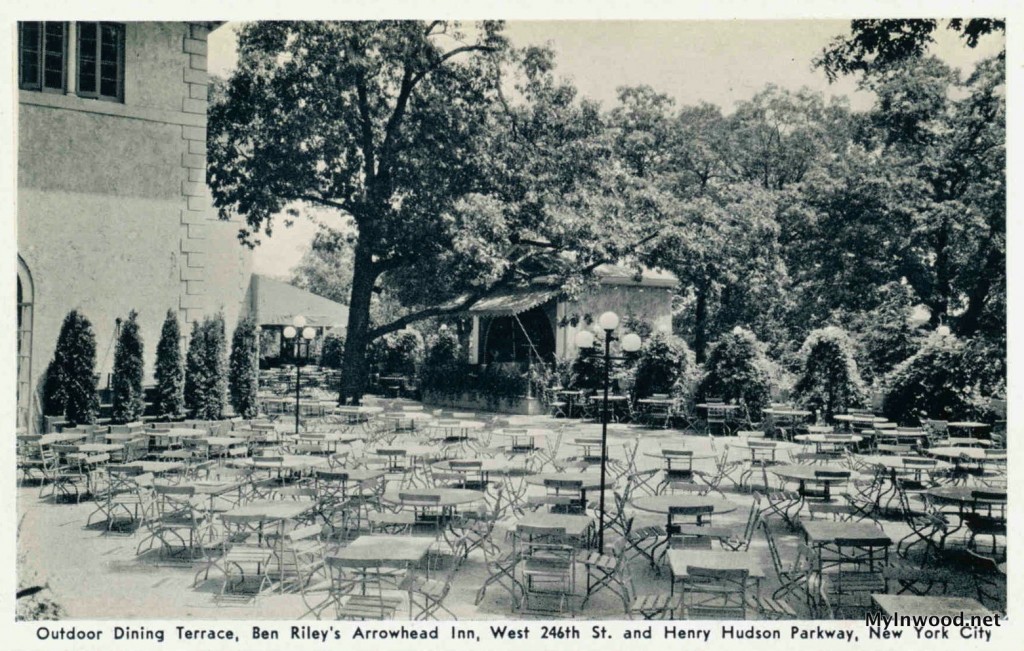

!["In the absence of fire-fighting equipment, the trainmen, passengers and men from nearby farmhouses used huge snowballs to combat the flames and facilitate the task of rescuing survivors from the wreckage." Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.]()

“In the absence of fire-fighting equipment, the trainmen, passengers and men from nearby farmhouses used huge snowballs to combat the flames and facilitate the task of rescuing survivors from the wreckage.” Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.

And, although badly burned about the face and hands, Hanford started to roll a snowball toward the terrible mass of burning timbers and hissing metal. Soon hundreds of willing hands were pushing great mounds of snow toward the danger spot. Some, braving the fierce heat, ran alongside the blazing cars and tossed the snow in through the windows. Others risked death themselves to drag out both the living and dead from the fiery hell-holes.

To enable rescuers to keep at work while removing the victims, their companions deluged them with water and pelted them with snowballs.

![Sketch of crash with inset of Webster Wagner.]()

Sketch of crash with inset of Webster Wagner.

At the moment of impact, the lamps in one end of the Empire went out. Those in the other end gave a light, which, pale and sickly though it was, proved to be a blessing. With this illumination every occupant of the Empire was enabled to get out or be carried out alive before a wall of fire made exit impossible; and no one perished in that car.

Until a year and a half before the accident the N.Y.C. & H.R. had lighted cars with candles. General Superintendent John M. Toucey maintained that these were safer than oil lamps; but the traveling public had complained that they could not read by such light, and so oil lamps were substituted.

The cars were heated by the Baker patented process, not by stoves, and the heating apparatus was concealed from view. Nevertheless, according to Conductor Hanford, who had been in train service on that road for eleven years, this system was the cause of the fire, though oil lamps added to the conflagration.

Tons of snow were thrown upon the two cars, and in a short time the volunteer workers had the hills and roadway scraped almost entirely clear of snow. Even this, however, seemed hardly able to abate the heat. Late at night relief came with the arrival of the fire department from Carmansville, a wrecking train from the Thirtieth Street depot, and two or three ambulances made a long and terrible drive through the dark over snow-covered, muddy roads.

The fire apparatus, pumping water from the Hudson, soon put the fire out. But before this happened, the cars had been reduced to a shapeless mass of charred wood and twisted metal.

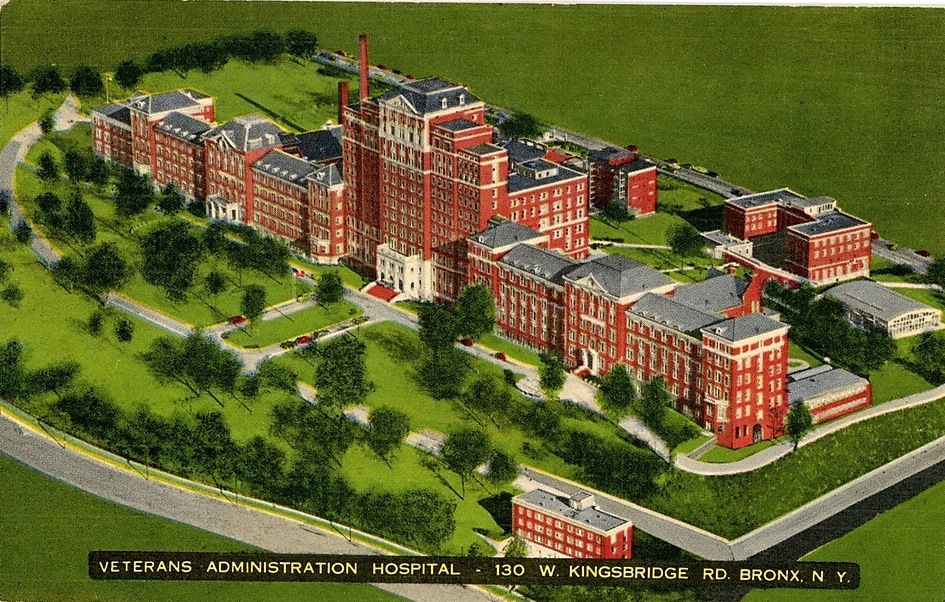

James Kilcullen threw open his place to the victims, dead and wounded alike. When the grim casualty list was finally counted, there were found to be eight dead – most of them burned beyond recognition – and nineteen persons were seriously injured.

The bodies were carried into Kilcullen’s saloon and there were laid, a ghastly spectacle, upon the floor and billiard tables. Two rival undertakers who had hurried over from Yonkers, N.Y., quarreled with each other as to which one should take charge of the bodies.

Aboard the wrecking train were General Superintendent Toucey, who was in charge of the entire N.Y.C. & H.R. Railroad between New York City and Buffalo, and Division Superintendent Charles Bissell. Both officials remained on the scene of the wreck all night, personally supervising the rescue work and disposal of the ruins.

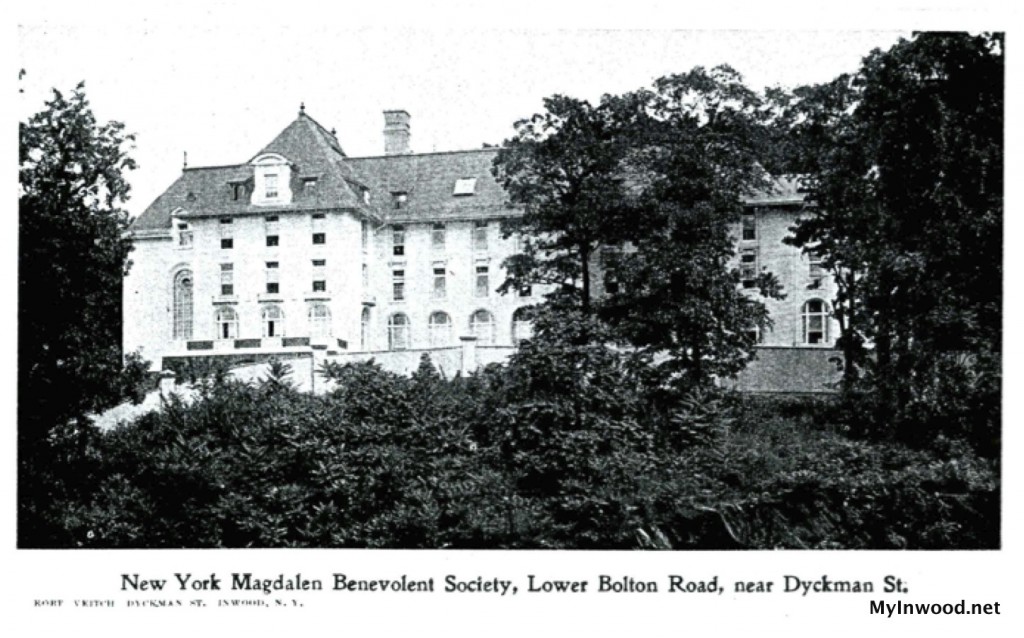

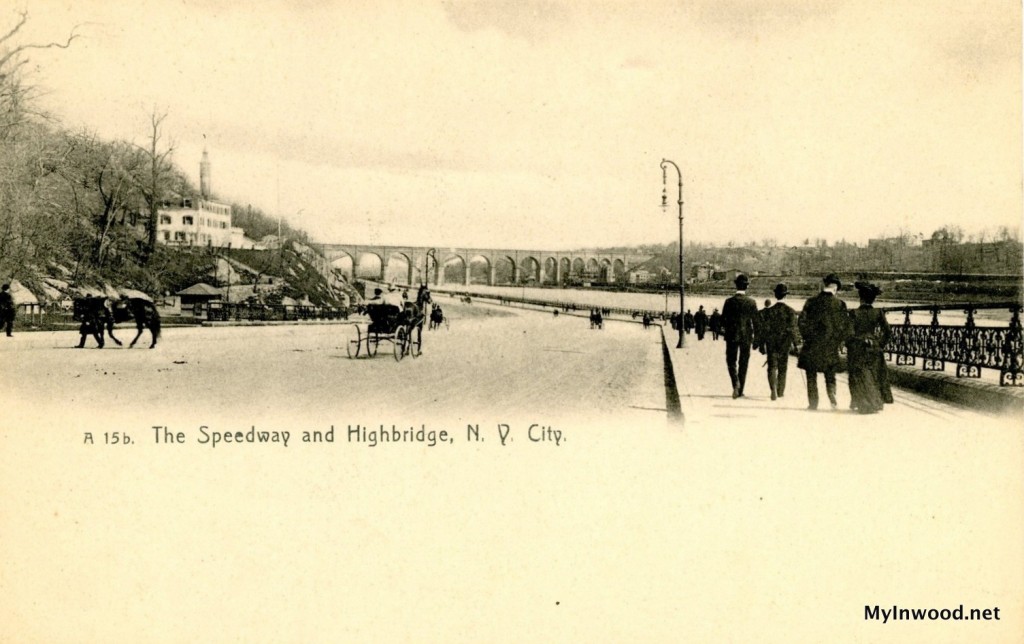

!["Clearing up after the wreck; Manhattan Island in the background; Kilcullen's Saloon at right." Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.]()

“Clearing up after the wreck; Manhattan Island in the background; Kilcullen’s Saloon at right.” Source: Railroad Stories, 1935.

By 4 A.M. the two tracks were cleared sufficiently for trains to run in both directions. The trains from New York brought a throng of newspaper reporters and curiosity seekers. Kilcullen’s thirst emporium did a land-office business, scores of men all day long drinking and playing billiards on the very spot where bodies of the wreck victims had been laid a short time before.

![The New York Truth, January 15, 1882.]()

The New York Truth, January 15, 1882.

The first of the dead to be identified was Senator Wagner. The famous inventor had perished in the Idlewild, with which he had sought to equip with every appliance of safety and comfort. Sorrowfully his son-in-law, Conductor Jay Taylor, claimed the body. One of the Wagner cars was draped with black and coupled onto a special train taking the Senator back to Palatine Bridge where he was born sixty-four years before, and where he had served the railroad for seventeen years as station agent.

Another of the dead was the Rev. F.X. Marechal, chaplain for Blackwells Island, New York City – the spiritual advisor for inmates of the workhouse, the insane asylum and the almshouse. He, too, was burned to death in the Idlewild.

So were Mr. and Mrs. Park Valentine, a young bride and groom who had been married the night before at a fashionable society wedding in New England. He was twenty-two; she was nineteen.

Conductor Hanford was the last person to see the newlyweds alive. Forcing his way into the shattered and burning car, he saw the devoted pair standing together in the wreckage. Mr. Valentine was trapped beyond all hope of being extricated. His bride was clinging to him; only her clothing was caught in the wreckage.

Hanford said later that if she had been willing to slip out of her clothing and leave her husband she could have been saved. This he urged her to do, but the hysterical girl refused to obey. The heat was too intense for Hanford to stay in there long enough to force her to do this, to save the woman in spite of herself, and so the young couple died together.

Immediately after the accident, according to A.H. Catlin, who had charge of the road’s air-brake equipment, the brakes on the wrecked train were examined and found to be in good working order. Just who had pulled that cord, at the height of revelry back there in one of the cars, will probably never be known.

Mr. Toucey, however, picked on Conductor Hanford and Brakeman Melius, particularly Melius, as the prime scapegoats.

“The collision,” said he, “was a direct result of the violation of Rule Fifty-three.” Following is the rule he referred to, as stated in the N.Y.C. & H.R. Railroad rulebook:

Whenever a train is stopped on a road, or is enabled to proceed at slow rate, the conductor must immediately send a man with red signal at least half a mile back, on double track, and the same distance in both directions if on single track, to stop any approaching train, which signal must be shown while the detention continues.

This must always be done whether another train is expected or not. In carrying out these instructions the utmost promptness is necessary; not a moment must be lost in inquiry as to the cause of stoppage or probably duration; the rear brakeman must go back instantly. Conductors will be held strictly responsible for the prompt enforcement of this rule.

At the coroner’s investigation, the attorney for Melius asked the general superintendent: “Suppose one of the employees cannot read. How should he know what the rules are?”

Mr. Toucey replied: “If there is such a man he ought to leave the employ of the road.”

“Do you know of any such?” persisted the lawyer.

“I do not,” said Mr. Toucey.

Then the truth came out. Although George Melius had been employed in train service on the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad for more than twenty years, he could neither read nor write!

It did not take the coroner’s jury long to reach a verdict. They held that eight persons had been killed “by criminal means and culpable negligence in the performance of their several duties” on the part of brakeman Melius, Conductor Hanford, Engineers Stackford, Buchanan and Burr, General Superintendent Toucey, and the railroad company itself.

Later the grand jury indicted Hanford and Melius on the charge of manslaughter in the fourth degree, and recommended:

(1) Discontinuance of the use of mineral oil for illumination in cars.

(2) Use of steam of hot water or hot air heating of cars instead of heating be direct radiation.

(3) Extension of the block signal system

(4) Larger train crews

(5) Employment of signalmen at all dangerous cuts and curves

(6) Trainmen and others holding responsible positions should be required to read and write.

(7) Inclusion of water pails and tools boxes containing axes, etc., on every train.

(8) The practice of giving free passes to legislators and others holding office under our state and city government is contrary to all proper ideas of good public policy and should be prohibited by law.

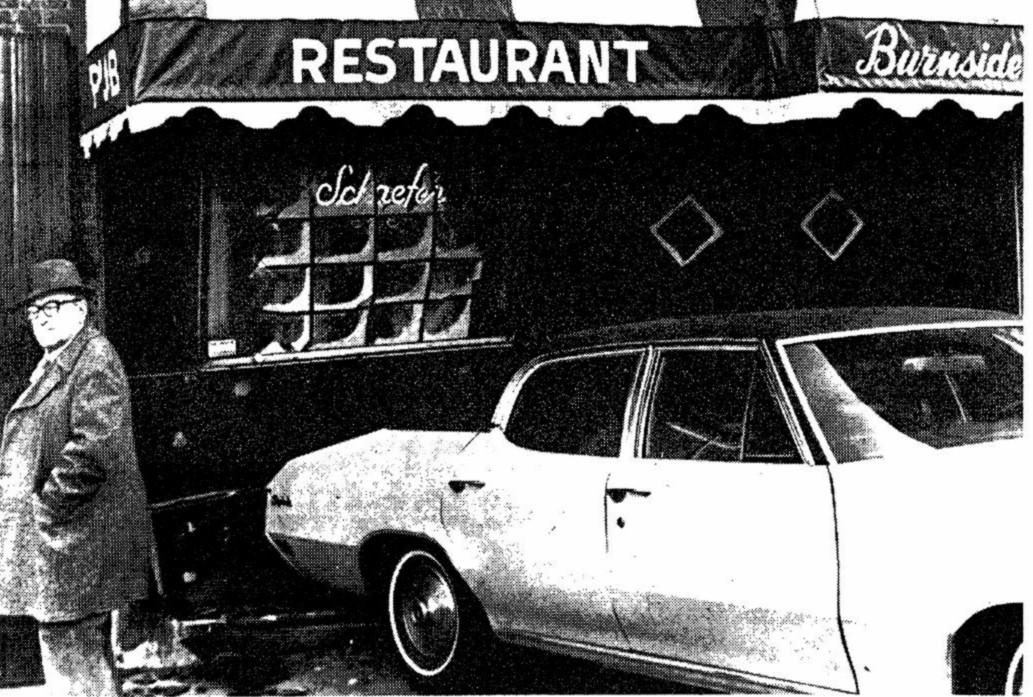

![George Melius, The National Police Gazette, February 4, 1882.]()

George Melius, The National Police Gazette, February 4, 1882.

On account of the death of Senator Wagner, who had been a member of important railroad committees, the Senate of New York State also made an investigation. Its report, June 1, 1882, was vague and obviously written by politicians; but was definite about one point, namely, putting the blame upon brakeman Melius and not upon any of the railroad officials.

An aftermath of this disaster was revealed in a recent letter from Richard McCloskey, of Co. 3, Veterans Administration Home, Va., who wrote to Railroad Stories on his seventy-fifth birthday, June 10th, 1935: “I was a witness of the wreck at Spuyten Duyvil and knew George Melius. About a year after the wreck I boarded a horse car on Second Avenue, New York City, and recognized Melius as the driver. He was well disguised by a long growth of whiskers.”

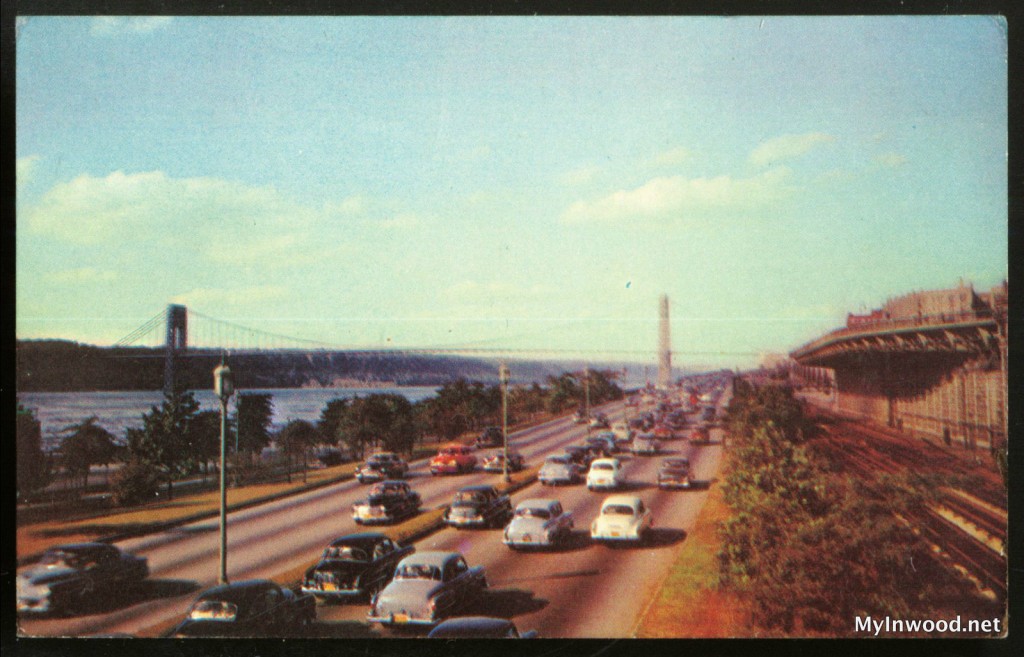

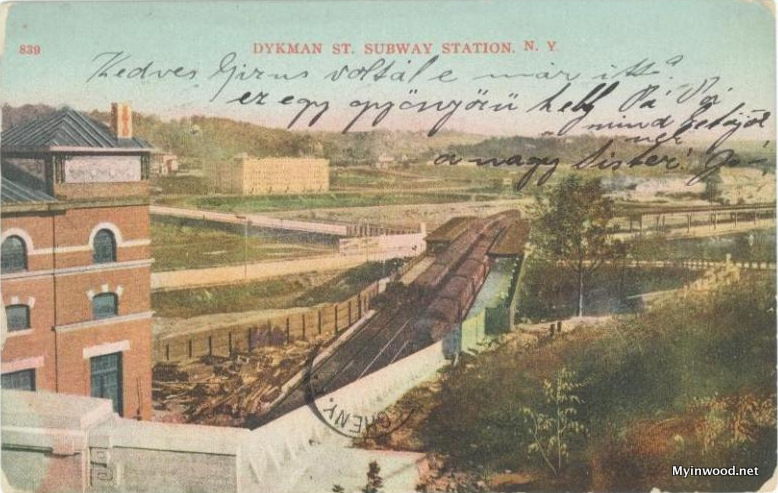

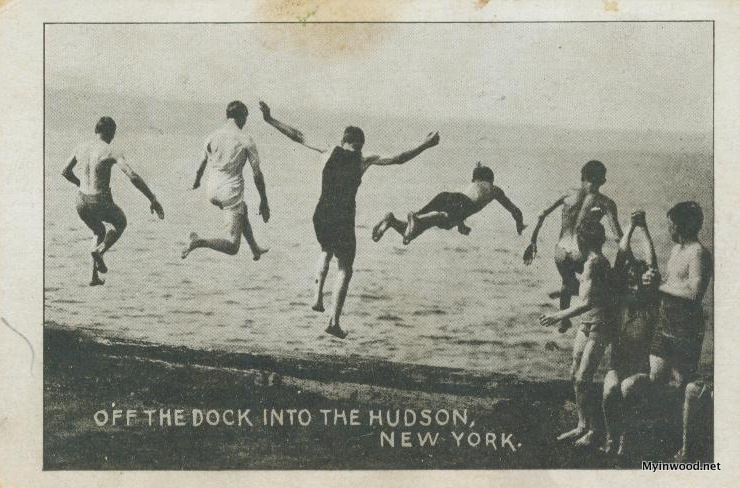

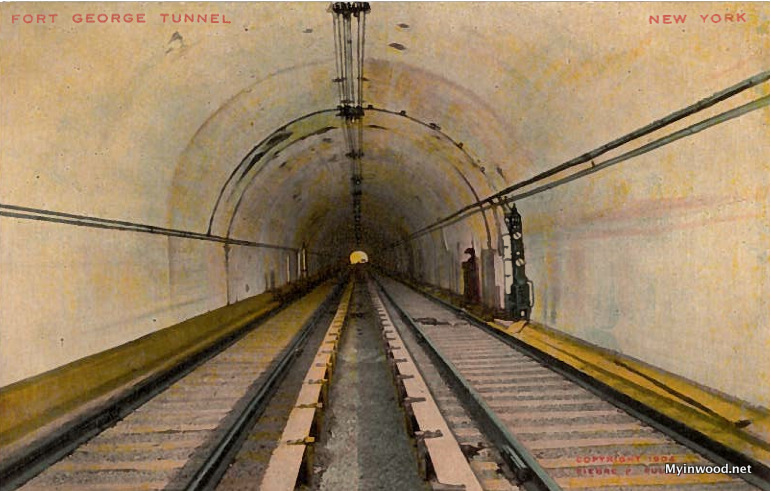

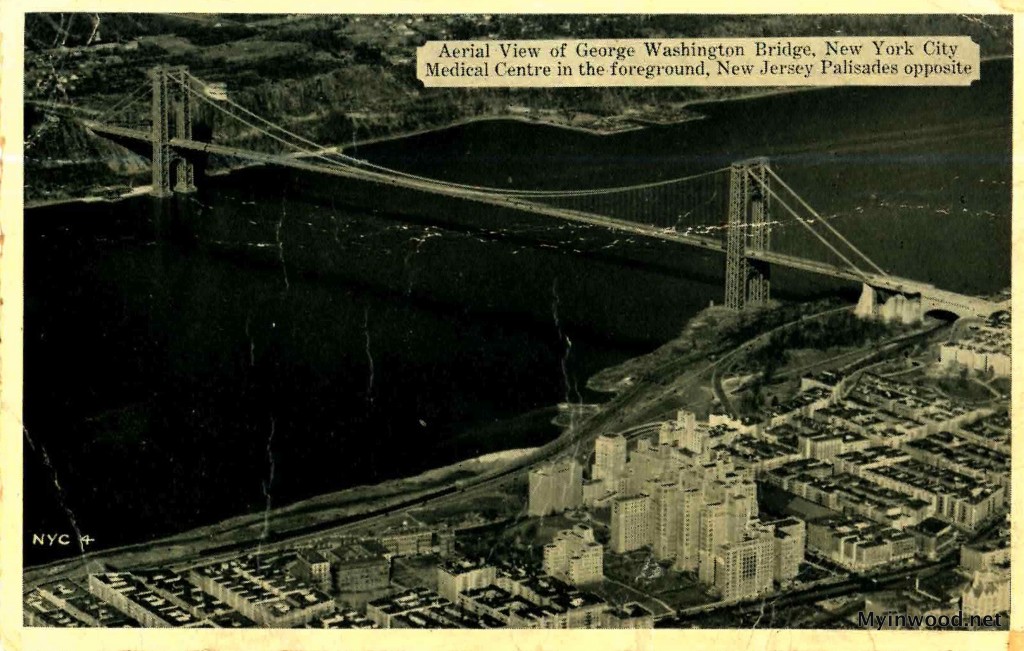

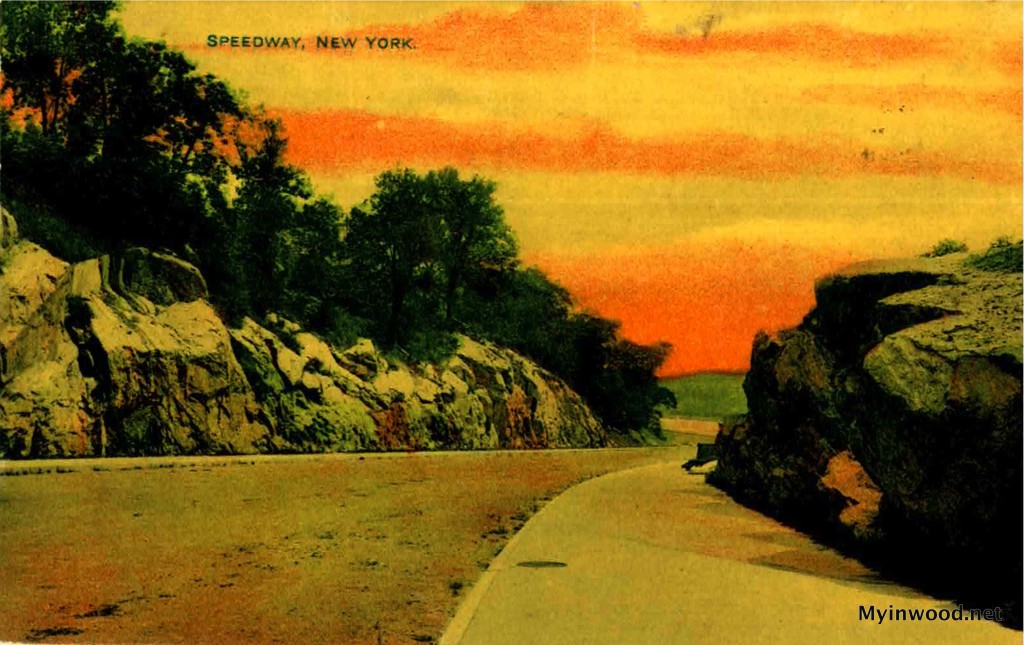

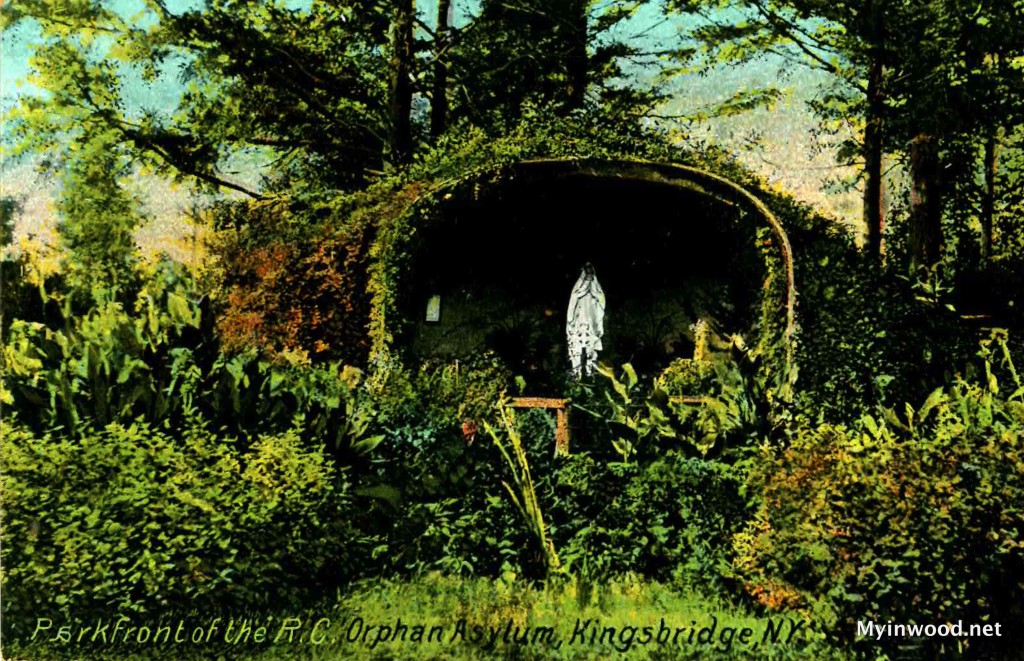

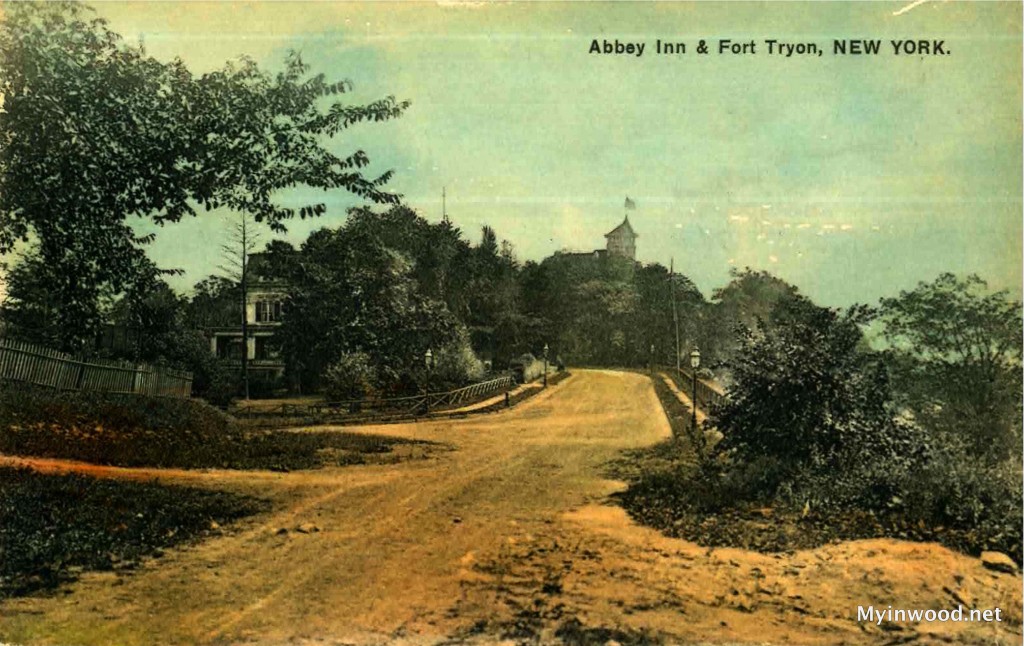

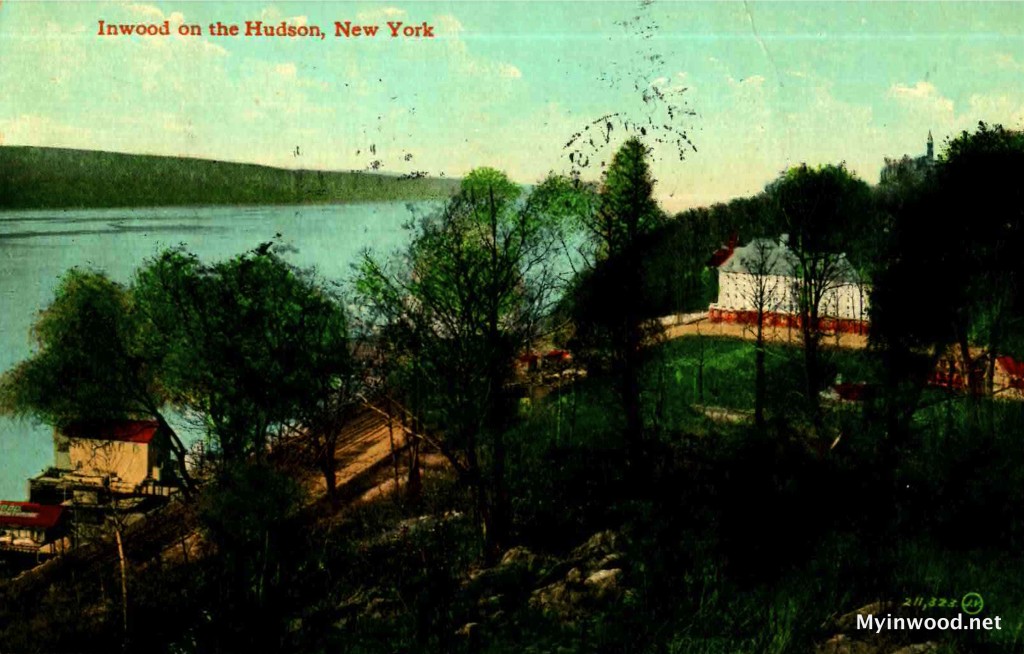

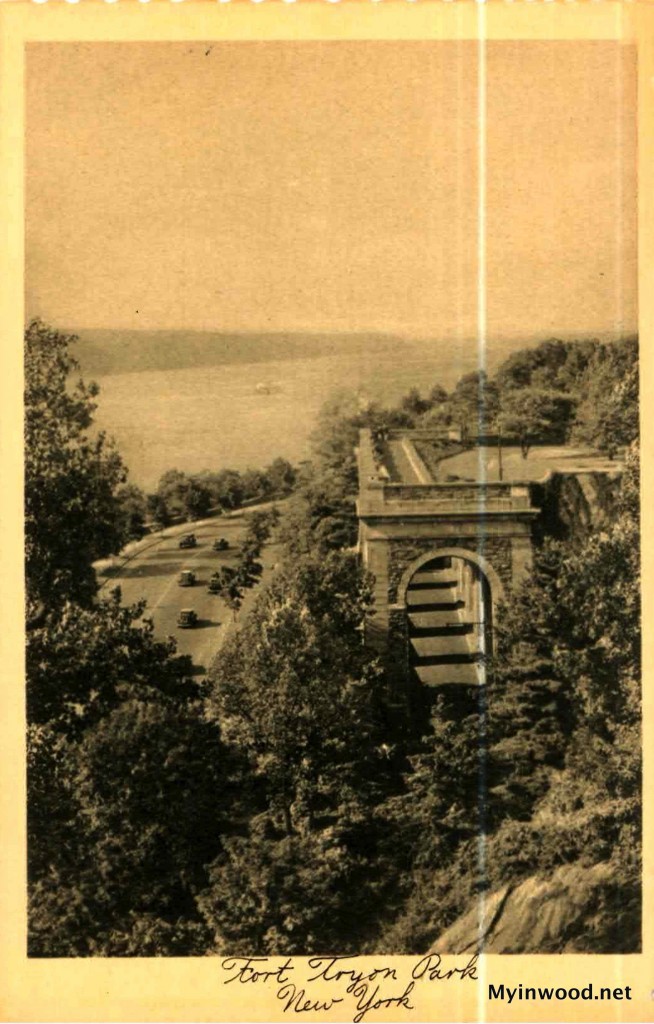

![Spuyten Duyvil Station, 1907.]()

Spuyten Duyvil Station, 1907.

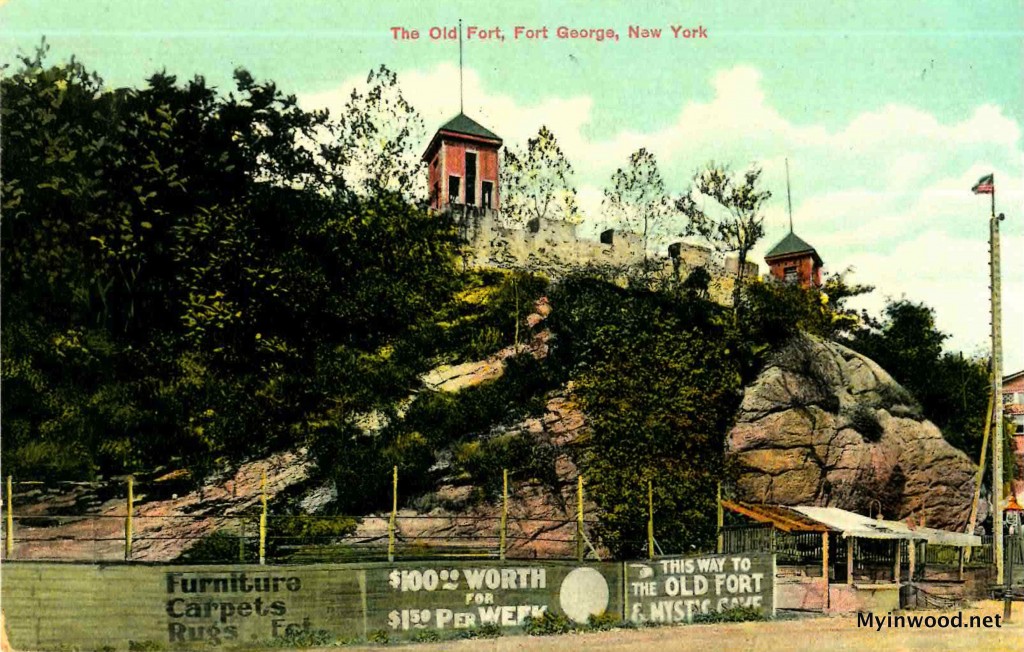

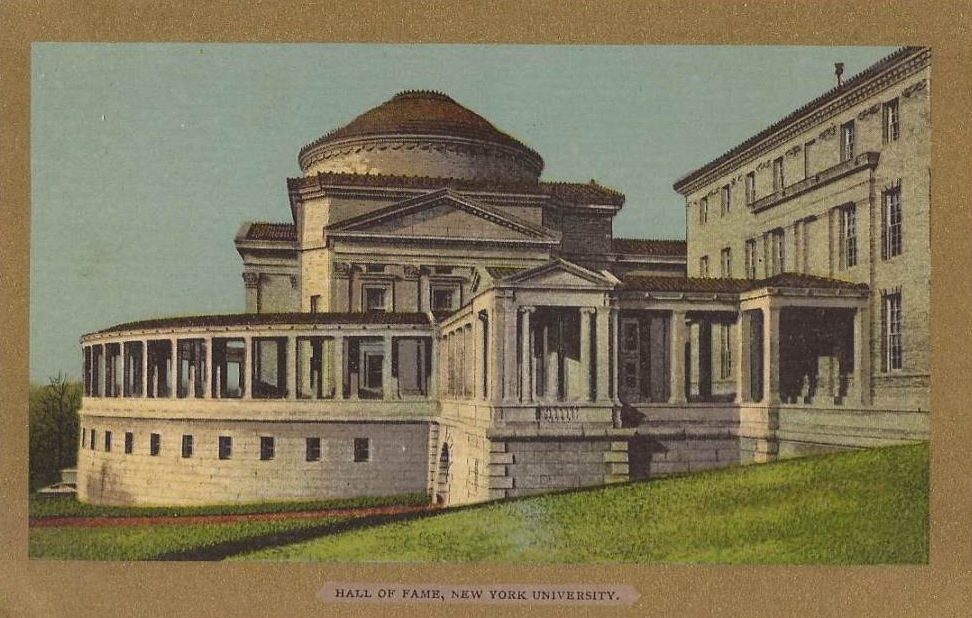

![Northwest view of crash site area across the Spuyten Duyvil shot from Inwood.]()

Northwest view of crash site area across the Spuyten Duyvil shot from Inwood.

If any other Spuyten Duyvil witnesses are still living, the general yardmaster of RAILROAD STORIES wants to hear from them.