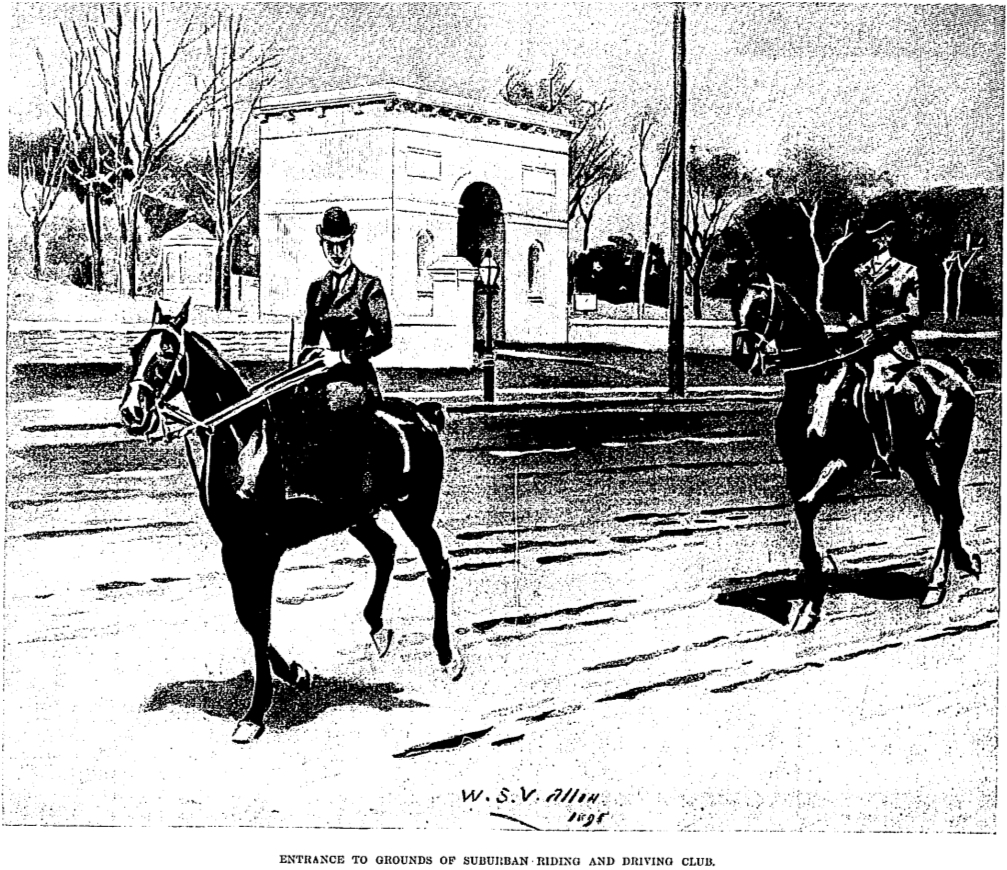

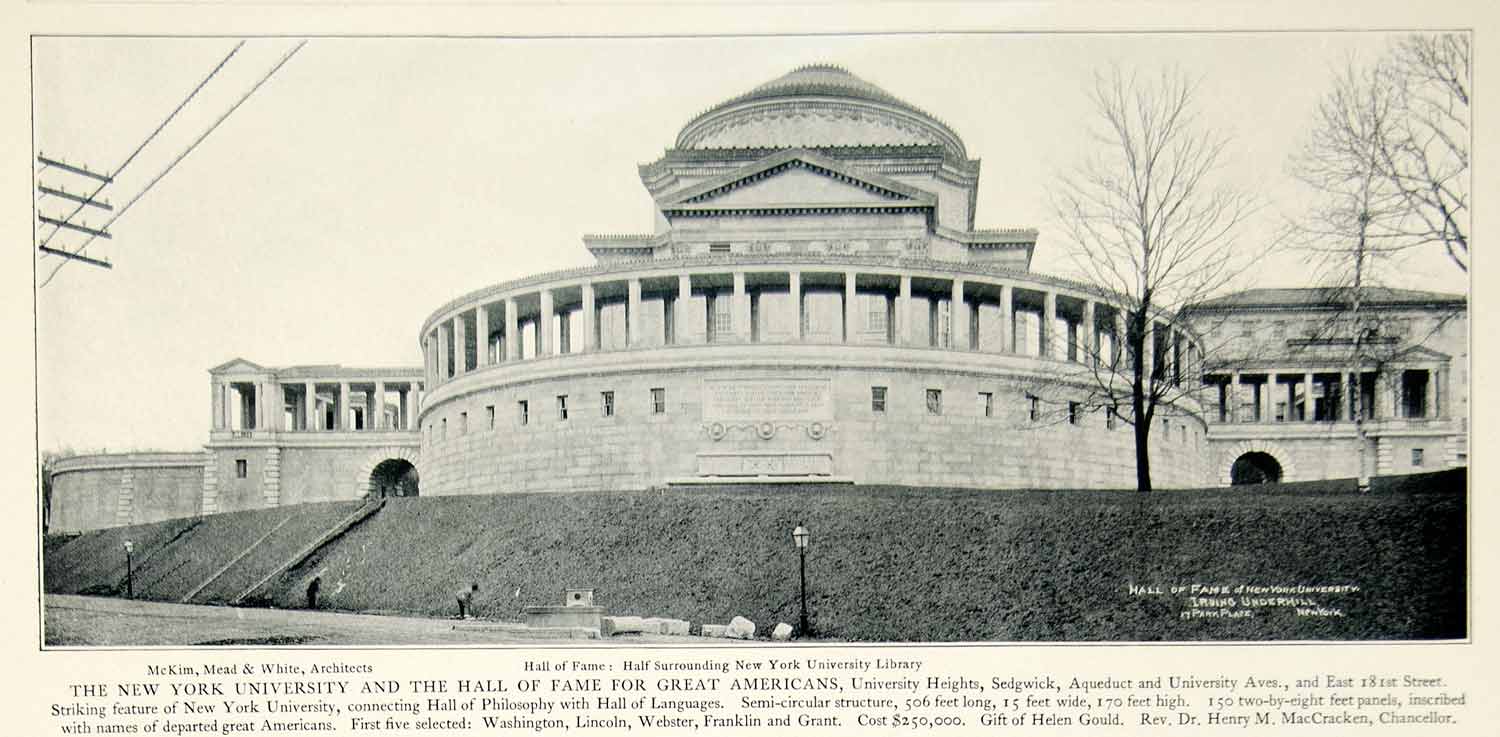

Much of what we know today about the history and pre-history of Inwood and Washington Heights is due largely to the turn of the century work of amateur historians, self taught archaeologists and close friends William Calver and Reginald Bolton. Starting in the 1880′s Bolton and Calver began exploring northern Manhattan with picks and shovels, chronicling their discoveries along the way.

![An Inwood dig site near the turn of the century. Reginald Bolton (left, sitting) and William Calver, standing to right of dig site.]()

An Inwood dig site near the turn of the century. Reginald Bolton (left, sitting) and William Calver, standing to right of dig site.

What you are about to read is an essay written by William Calver in 1932 describing those early days before the urbanization of Northern Manhattan. The original draft, written in fading pencil on lined legal paper, is housed in the Archives of the New York Historical Society.

“Recollections of Northern Manhattan”

W.L. Calver

3-10-1932

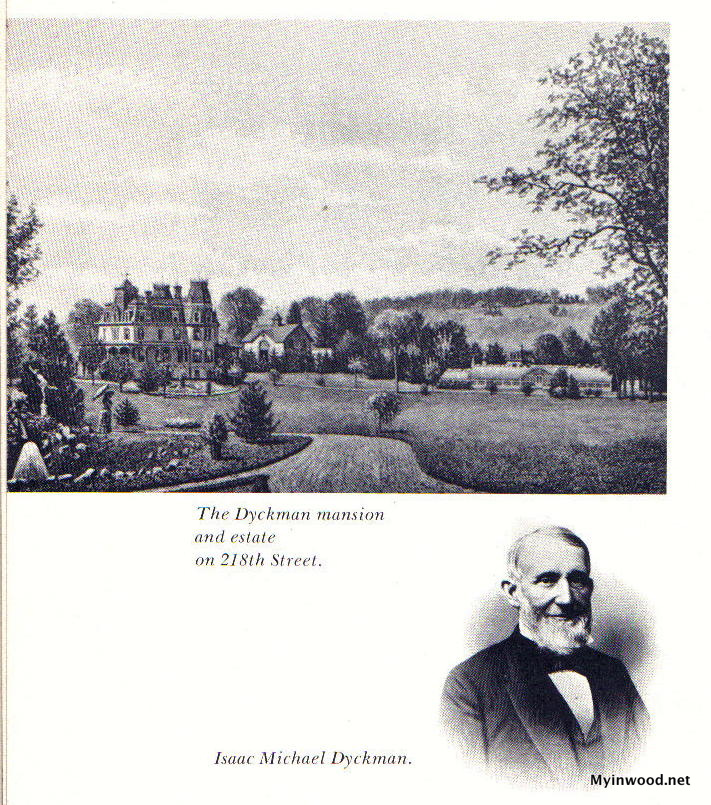

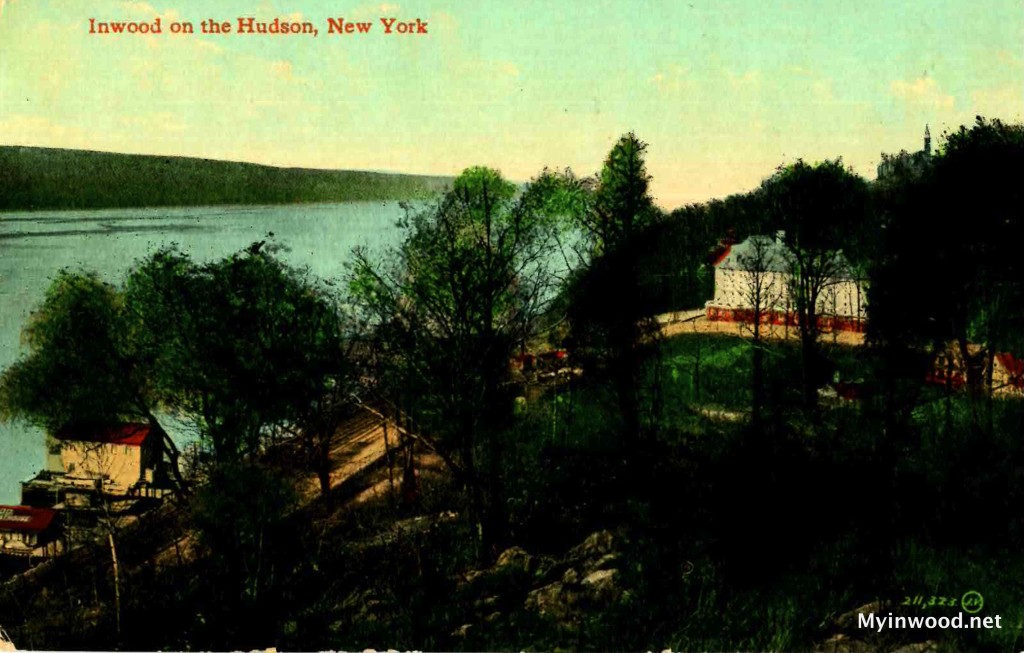

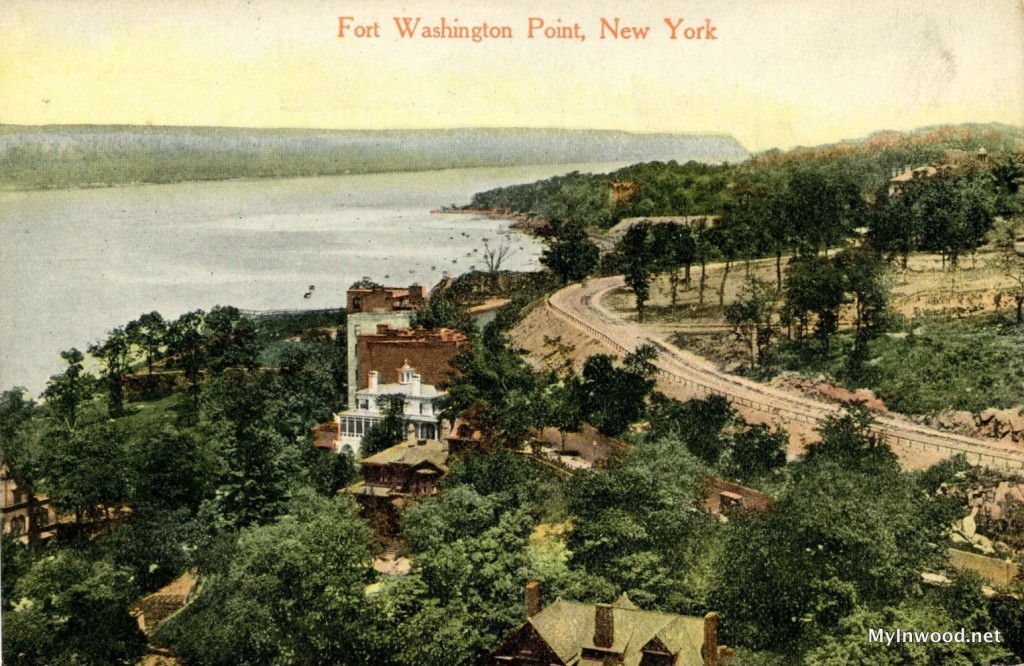

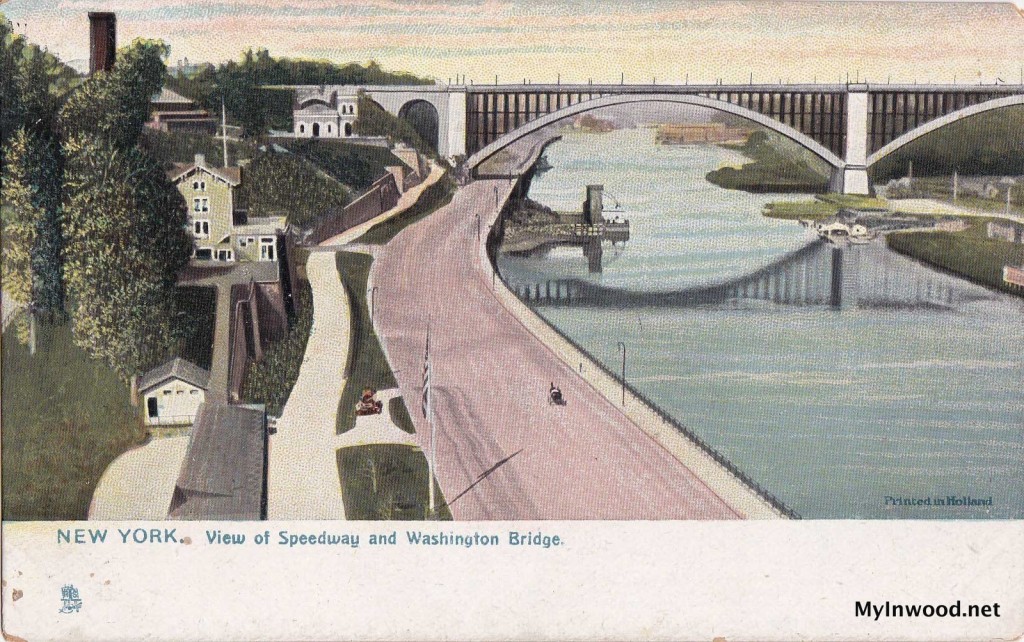

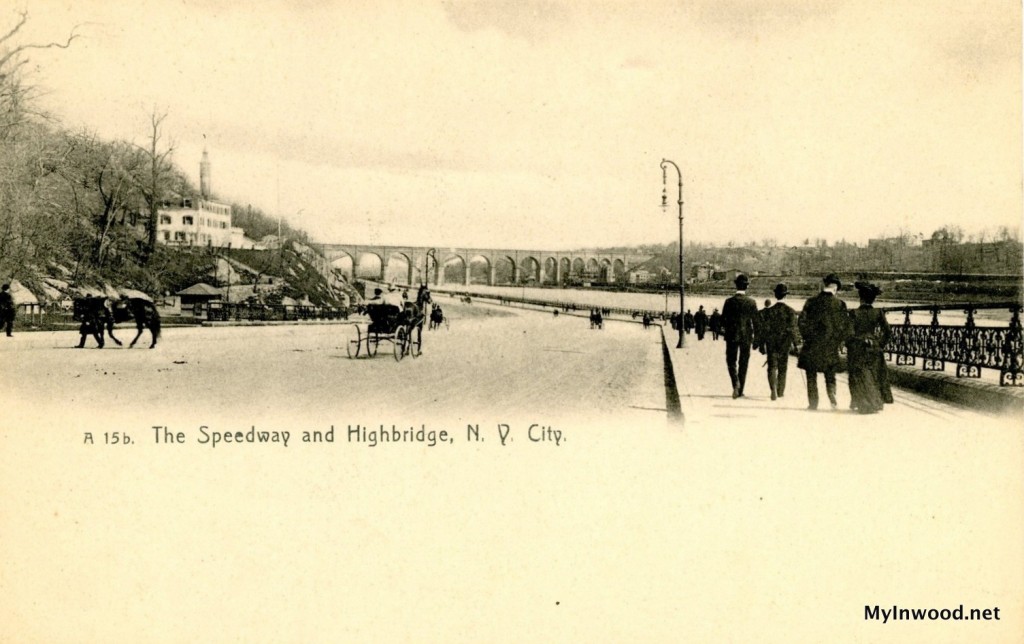

Back in the early 1880′s when the writer first became familiar with that section of Manhattan Island known as “Inwood” it was only a fairly good class of humor when a reporter for one of the city newspapers alleged that in the course of a visit to northern Manhattan he had conversed with a farmer who declared that he had not been down to New York for the past twenty five years. The agriculturalist had been promising himself, however that he would be making a pilgrimage that way before long for he had heard that great changes had taken place to the Southwest and Yorkville had gotten to be as big as Harlem. Our own experience with Inwood in these far off days led us to believe that the scribe’s story might be at least-plausible.

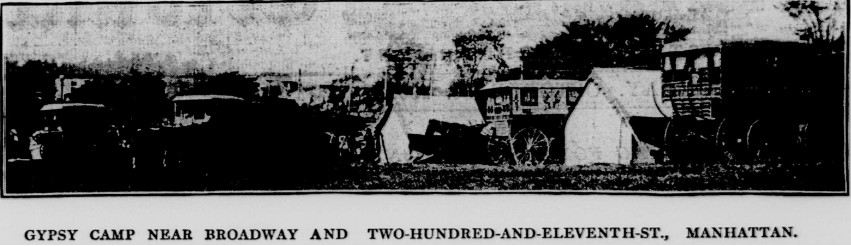

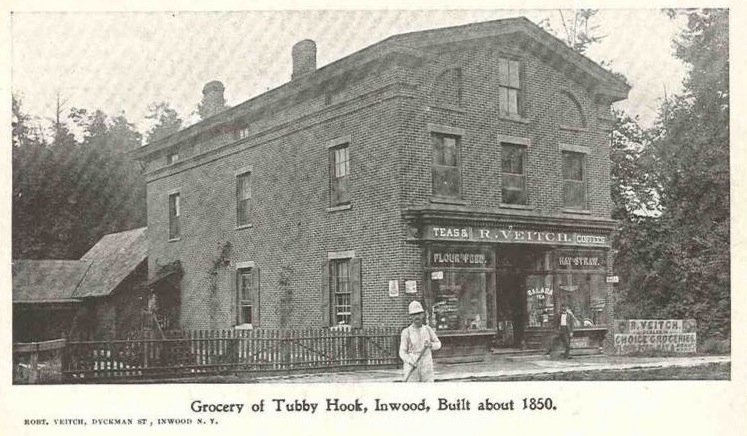

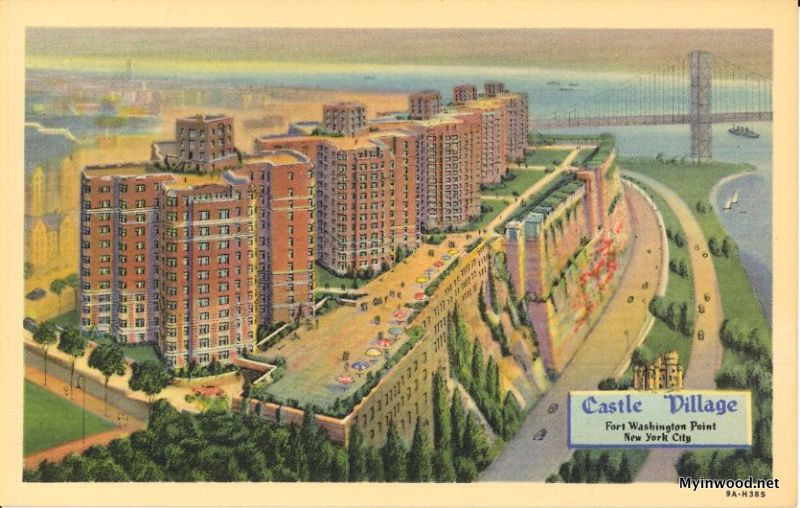

![Turn of the century postcard depicting Veitch's grocery on Dyckman just west of Broadway. Note the card reads "Tubby Hook" rather than "Inwood."]()

Turn of the century postcard depicting Veitch’s grocery on Dyckman just west of Broadway. Note the card reads “Tubby Hook” rather than “Inwood.”

The very name “Inwood” as applied to the locality in question was suggested by its ultra-rural character, and we ourselves got it from a venerable clerk of one of our courts that he in turn thus sponsoring the locality, on the occasion of his surrendering his trust for certain properties thereabouts in the 60′s, had good reasons for his choice of such a name. To nature lovers the name was attractive, but with the ultimate expansion of the City the appellation of “In-wood” was anathema to the promoters of real estate, tough prospective buyers went further and fared worse.

![View of the Kingsbridge Road, Valentine's Manual, 1866.]()

View of the Kingsbridge Road, Valentine’s Manual, 1866.

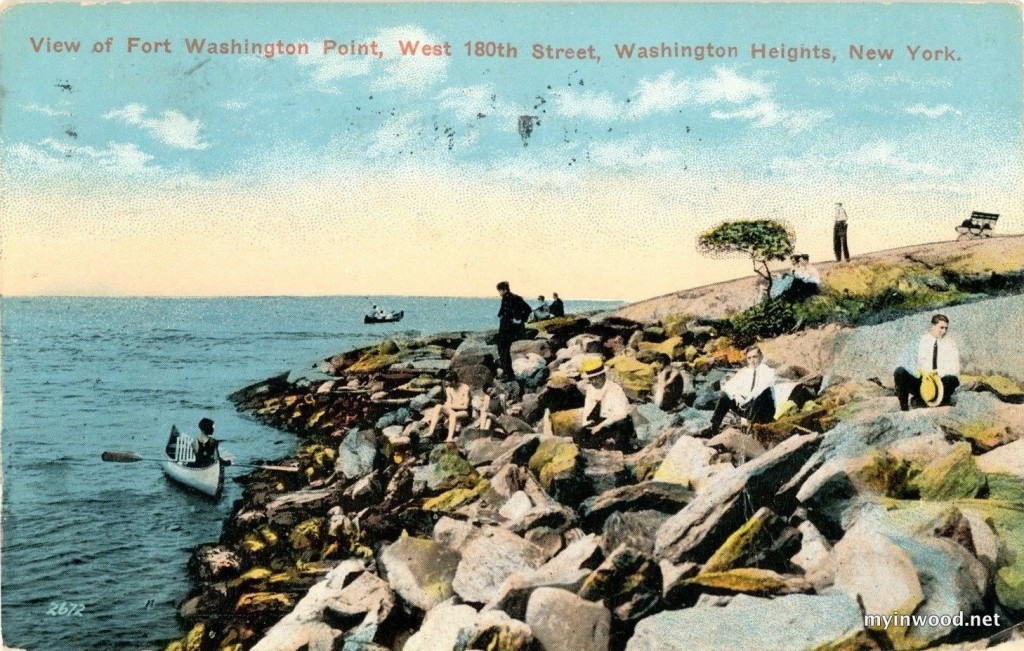

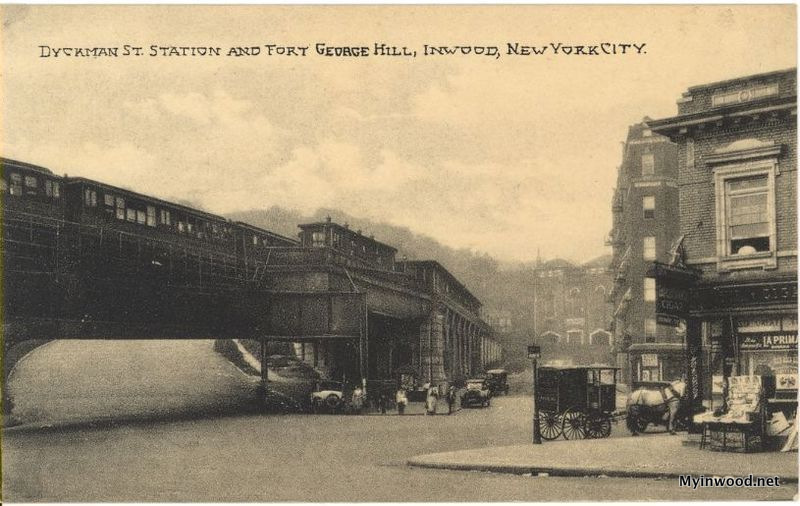

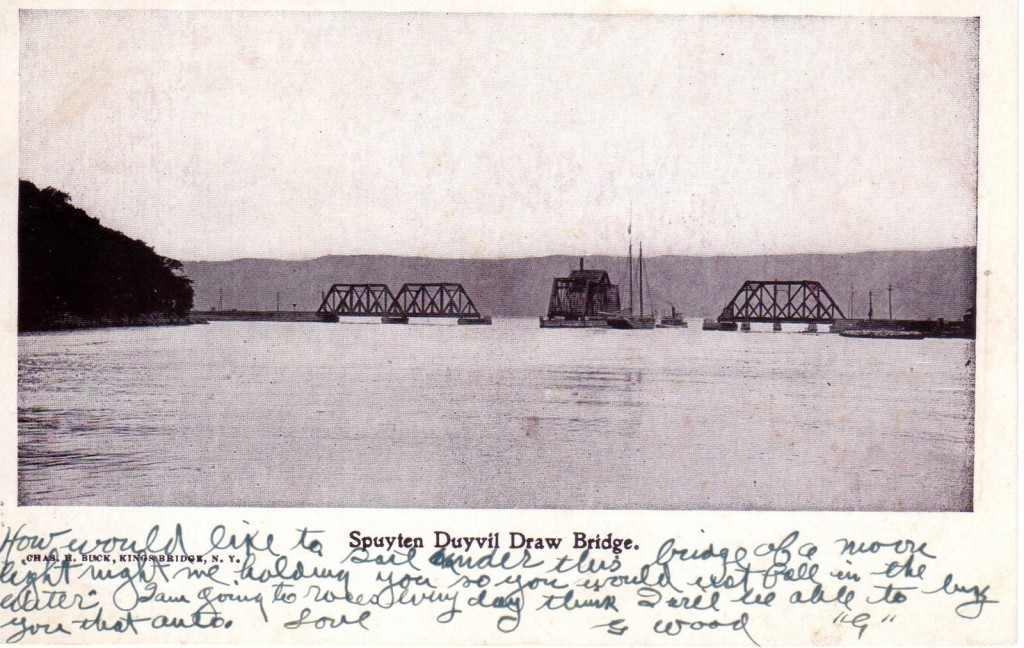

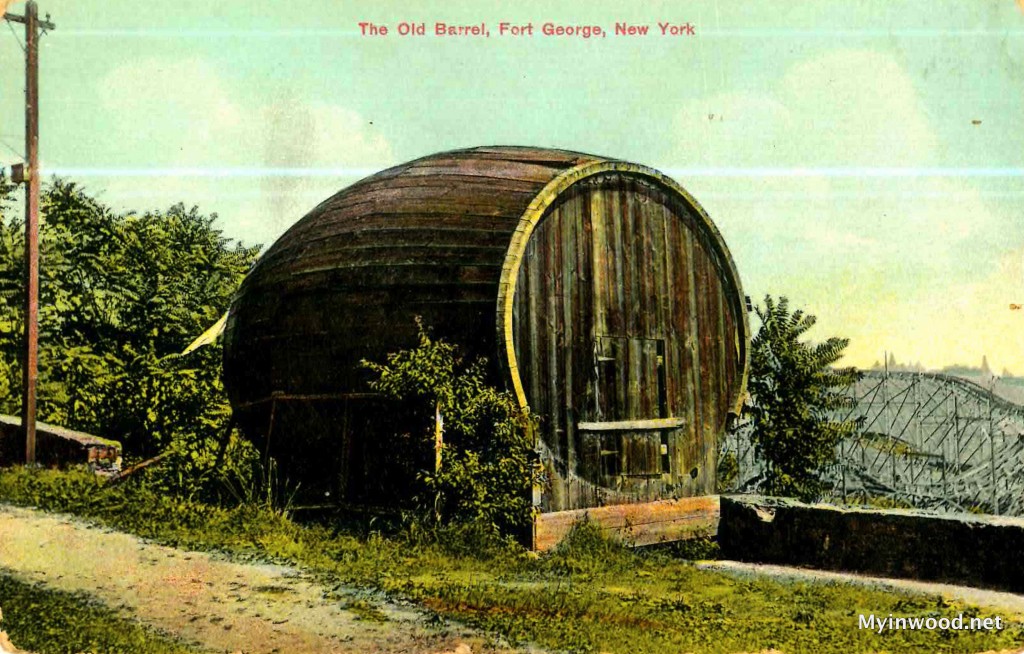

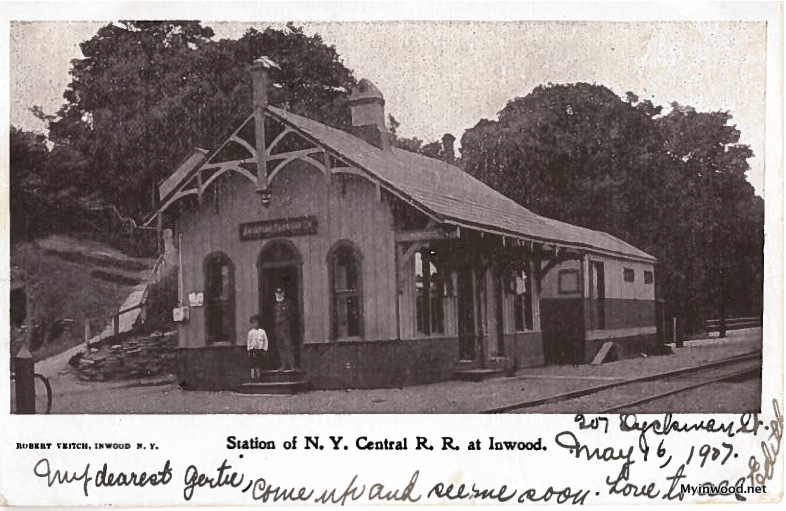

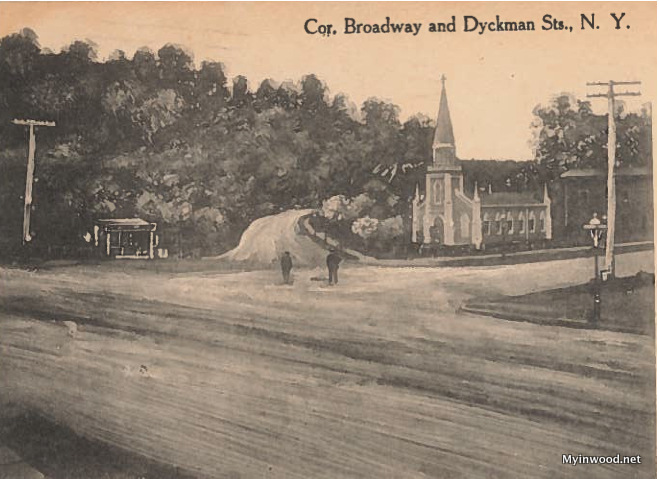

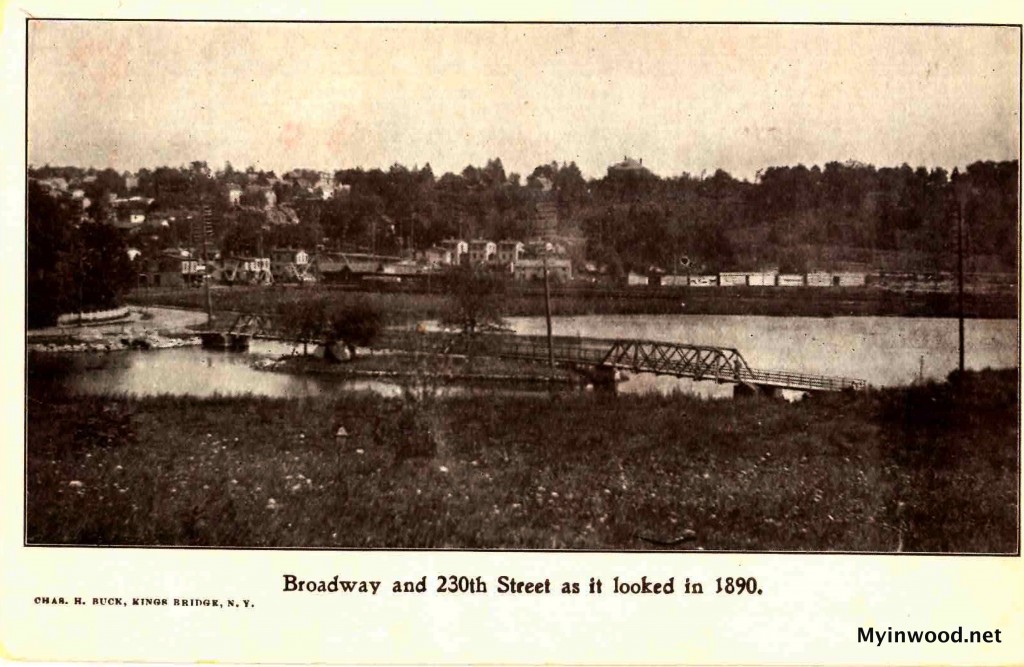

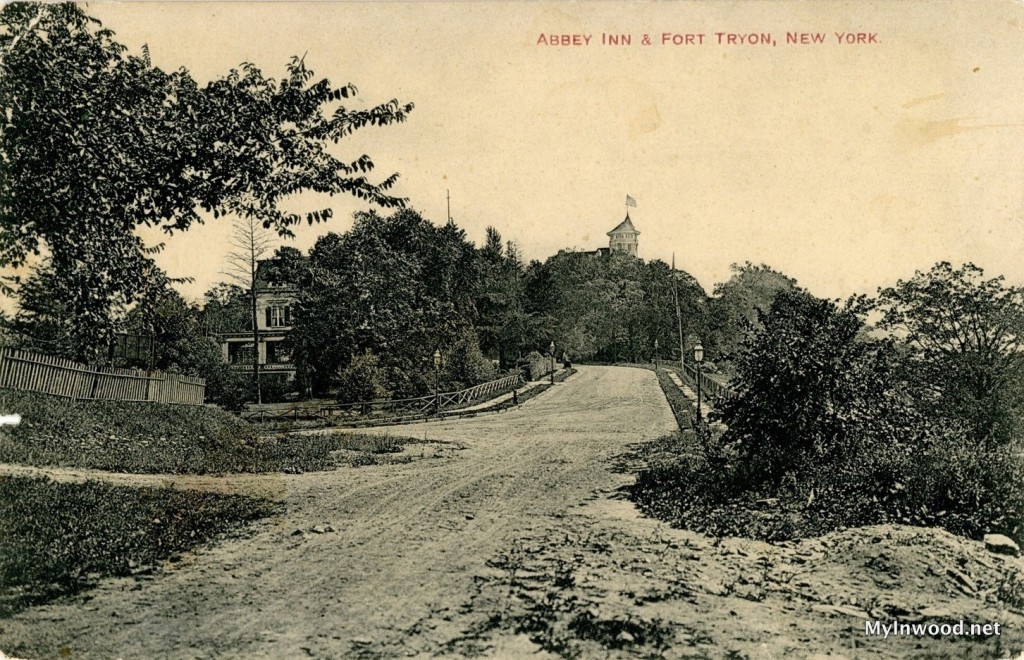

While dealing with names we would say that in Revolutionary days all of the northern end of the island was known as “Kingsbridge,” as in our day the settlement contiguous to the old bridge-on its northerly side-is so called. Previous to the adoption of the present name of “Inwood” the locality bordering on the present day Dyckman Street-west of Broadway, was called “Tubby Hook.”

![The last of the Kingsbridge The last of the Kingsbridge]()

The last of the Kingsbridge

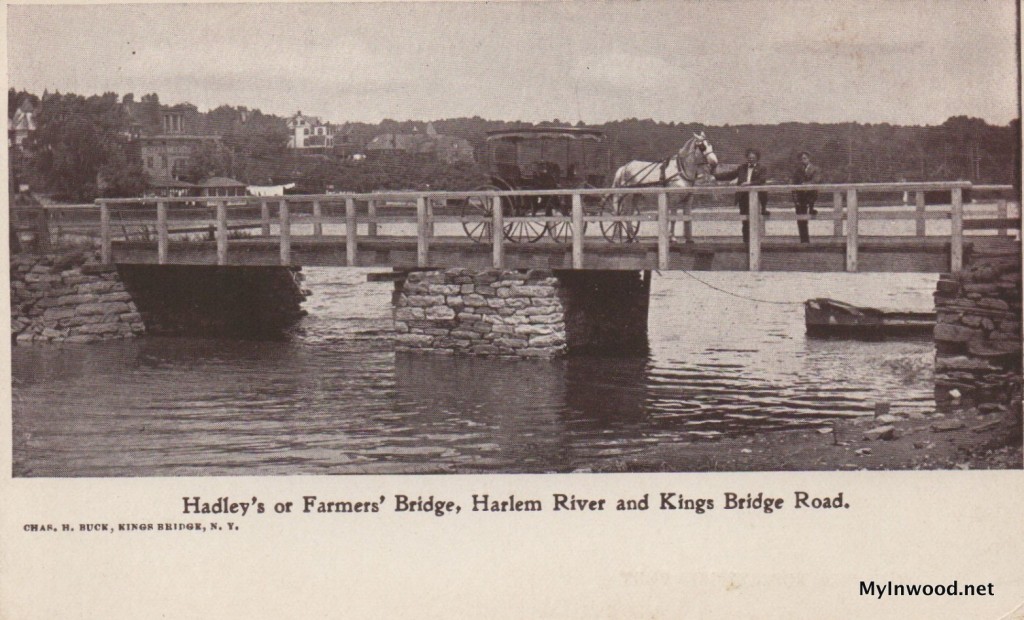

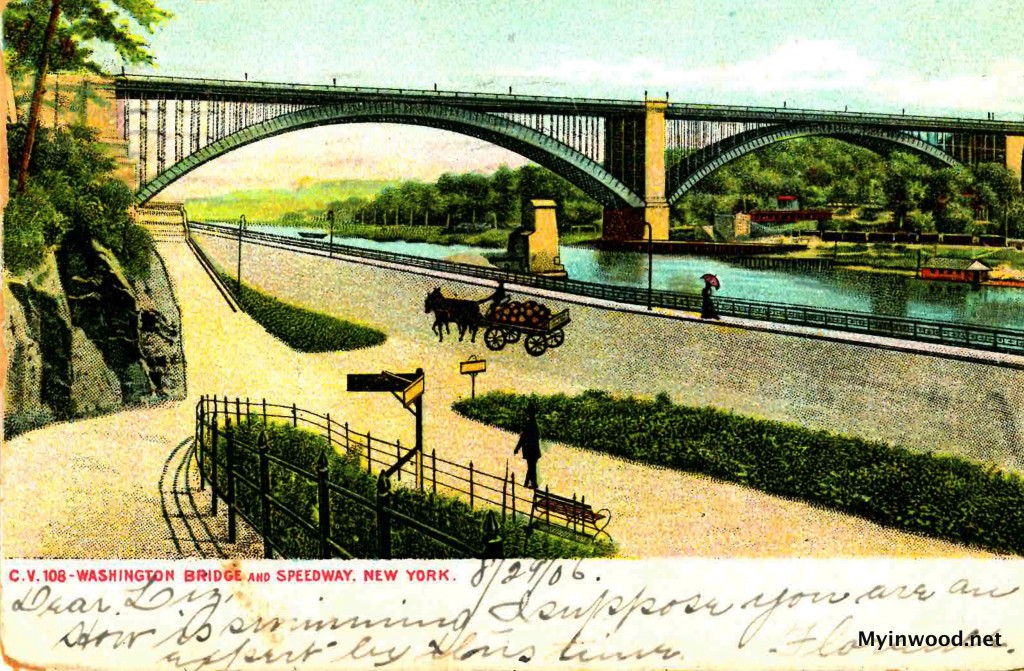

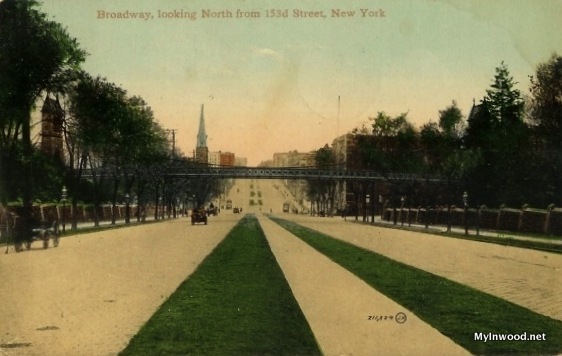

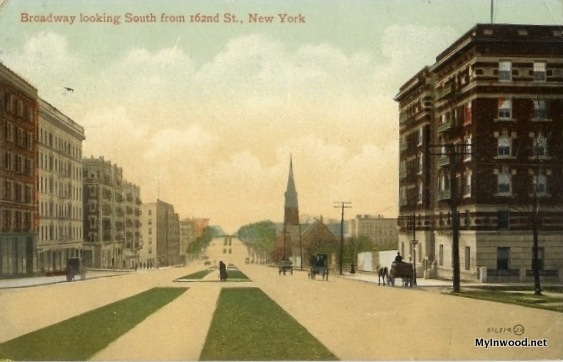

Because the farmer of the 1880′s had not been to town for many years past it has not to be inferred that Inwood was independent of the outside world. The peddler on learning the city to start out on his rounds to the northward passed along the old “Kingsbridge Road” -now Broadway- reckoned on a lessening of his load by the time he reached the bridge to the mainland that ancient structure we will remember the waterway it spanned has long ceased to exist.

![Spuyten Duyvil Creek in 1860. Dykeman's Bridge, Harlem River with King's Bridge on Spuyten Duyvil Creek in the distance, 1860.]()

Spuyten Duyvil Creek in 1860.

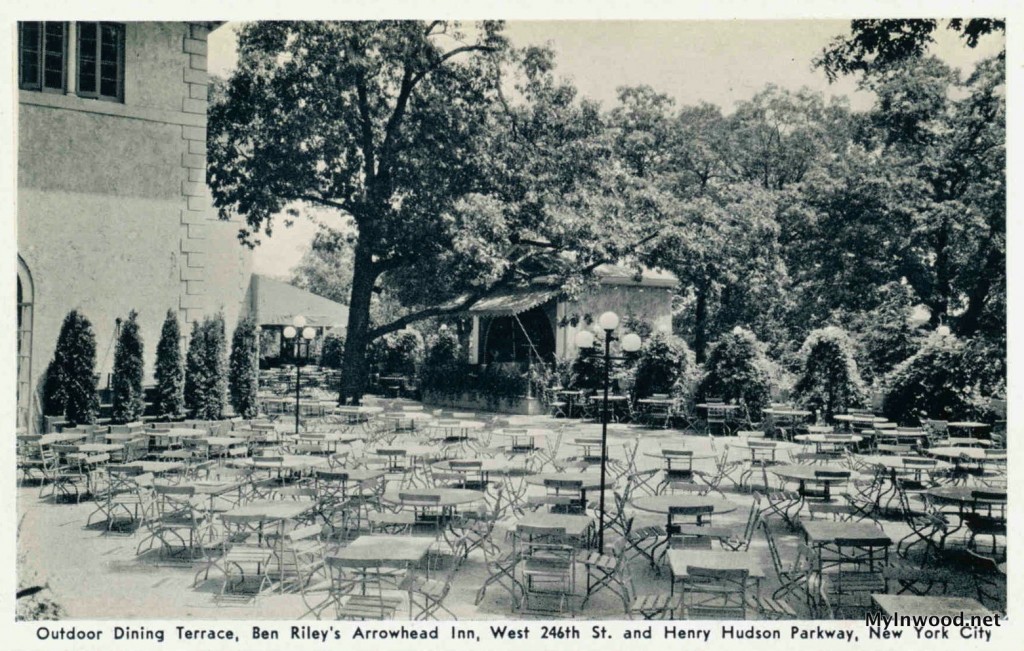

The rival bridge -”Dyckman’s Bridge”- we photographed for the last time in 1911. Peddlers or no peddlers the old-time resident of northern Manhattan did not suffer from want of wearing apparel, tin-ware or trinkets for Yonkers was-for those days-within easy walking distance and before the coming of the surface cars much more accessible than the 125th Street district.

![Dyckman House in 1890's, photo by James Reuel Smith.]()

Dyckman House in 1890′s, photo by James Reuel Smith.

In contrast with its rustic beauty and apparently pastoral innocence by day, the Inwood district was in the 80′s, and early 90′s, far from safe after the evening shades had fallen. The pedestrians one would meet then along the Kingsbridge Road might be a resident who was abroad on legitimate business, but the chances always were that travelers northward bound were desperados fleeing from justice, while other travelers southward bound were culprits of one sort or the another bent on hiding their identity in the big city; or were crooks journeying in from the provinces with their spoil.

Frequently, perhaps, they were of the latter sort; and in this connection we recall some stories told by a policeman of his nightly experiences along his beat. That beat covered half a mile of highway, and extended to the Harlem River to the eastward. The tales told by the officer convinced us at the time that an active and fearless policeman on night duty along the Kingsbridge Road had opportunities aplenty to win distinction.

![The old Kingsbridge Road, now Broadway, at 204th Street, photo by Ed Wenzel.]()

The old Kingsbridge Road, now Broadway, at 204th Street, photo by Ed Wenzel.

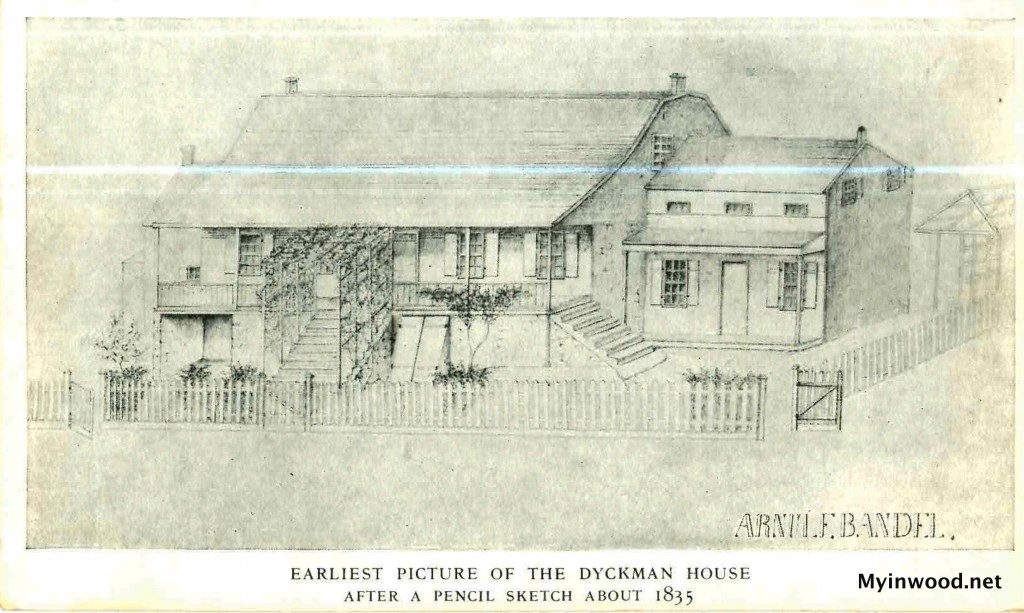

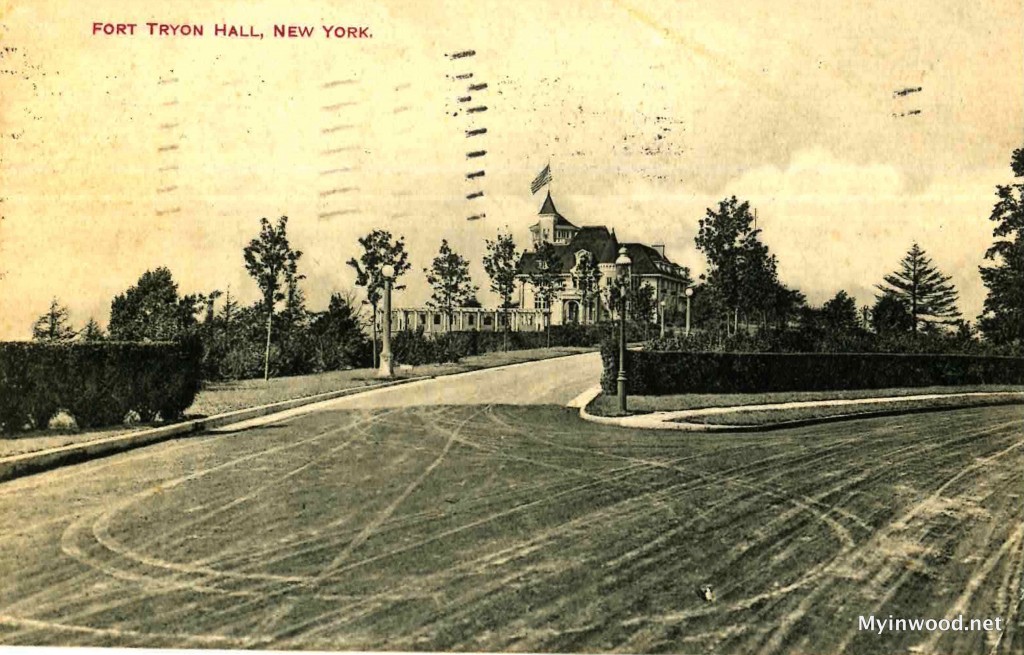

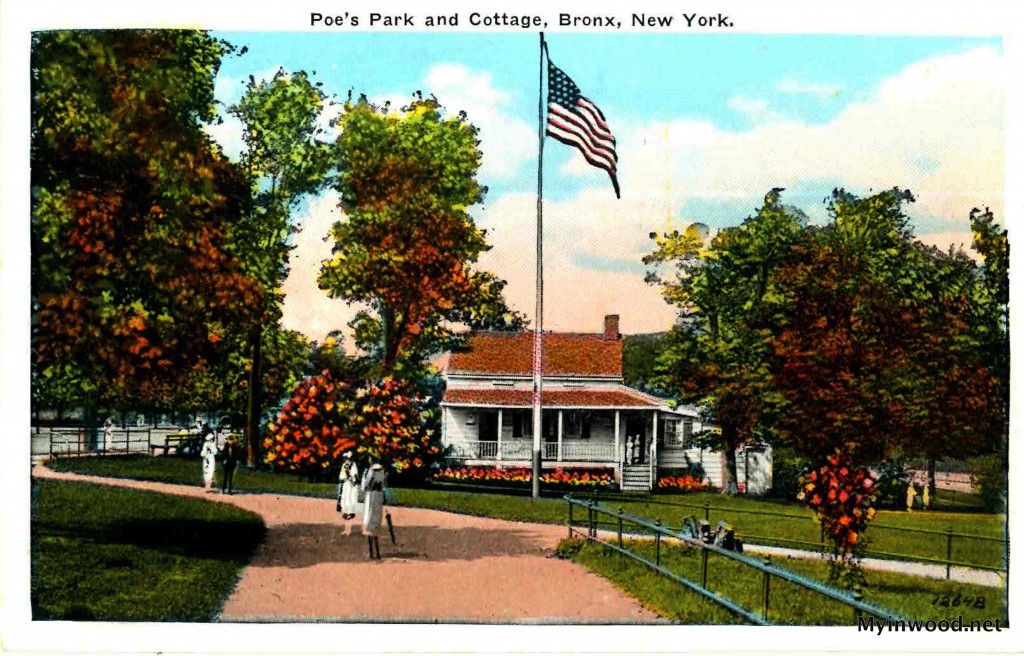

The Kingsbridge Road it must be remembered was, of old, the single artery of travel north and south, and was in all respects, typically a rural highway bordered on both its sides by fenced in areas with yet a few farm homes or tavern buildings which claimed an 18th century origin.

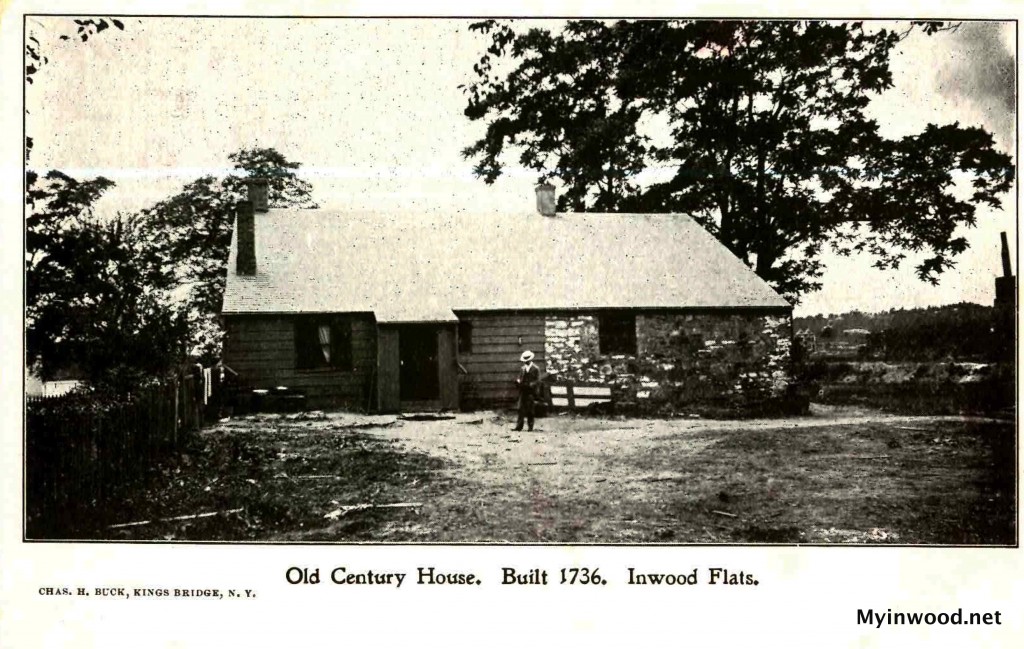

![Century House in 1892. Century House in 1892.]()

Century House in 1892.

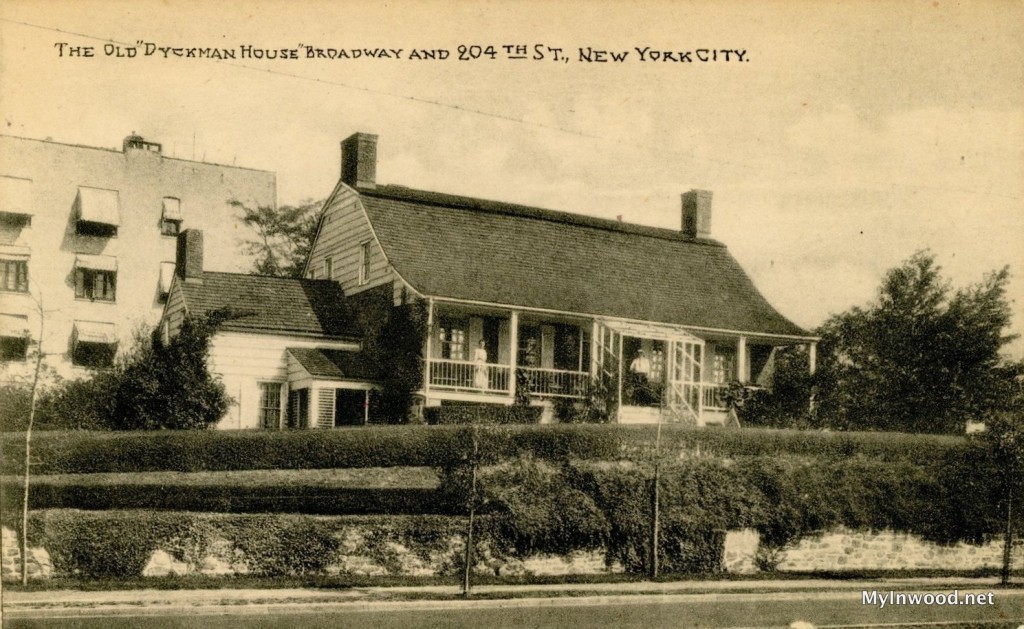

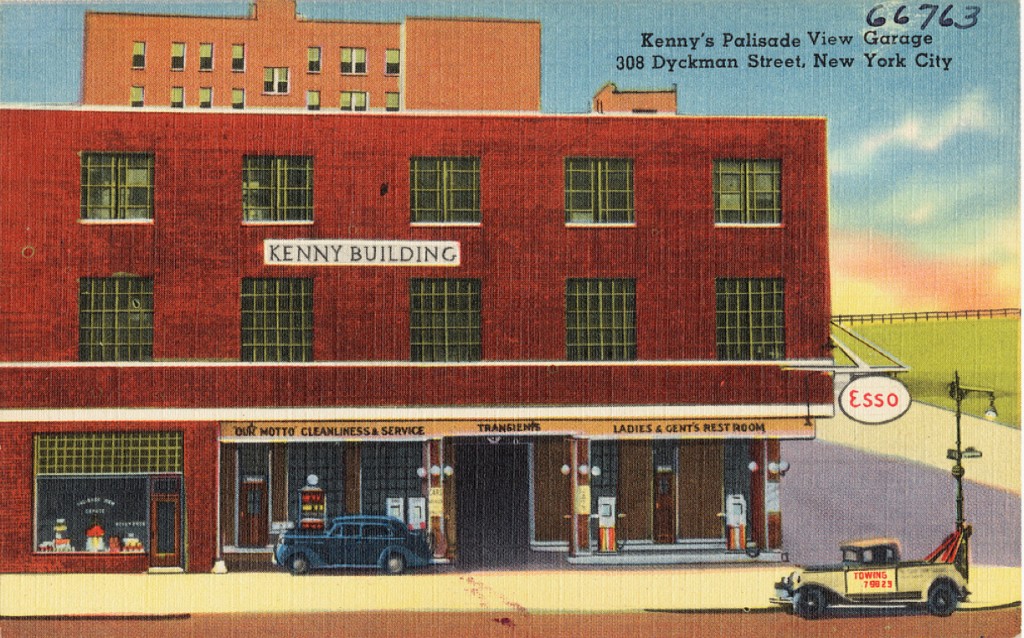

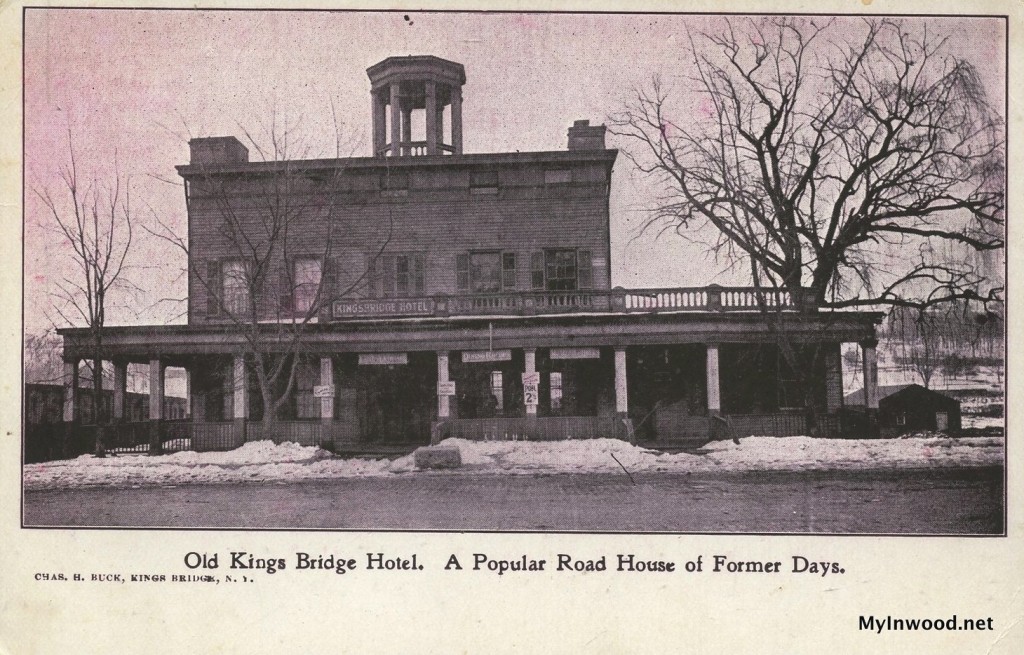

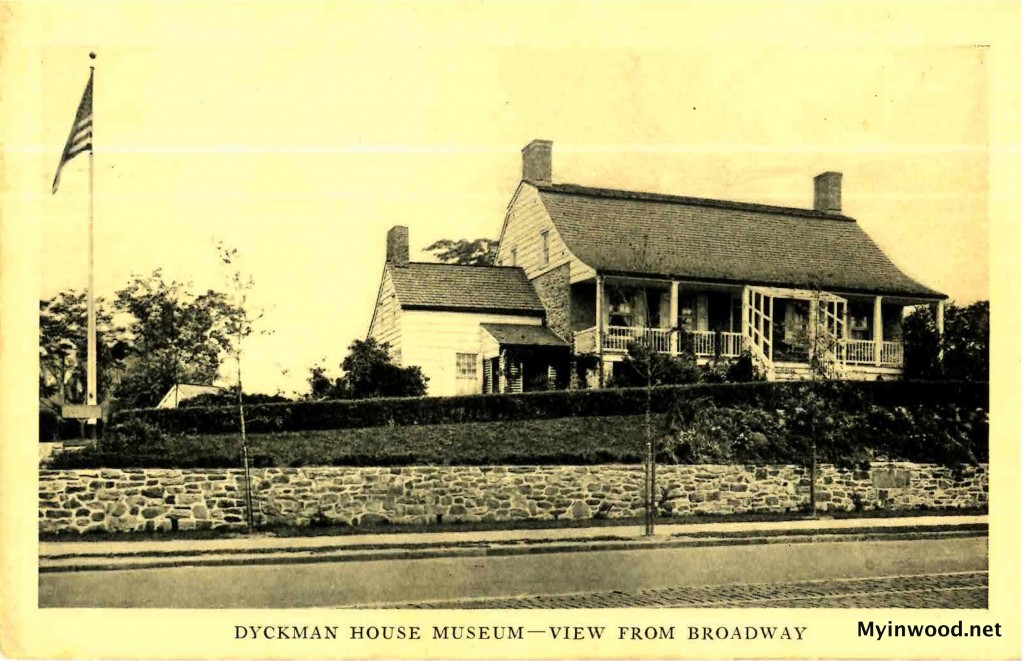

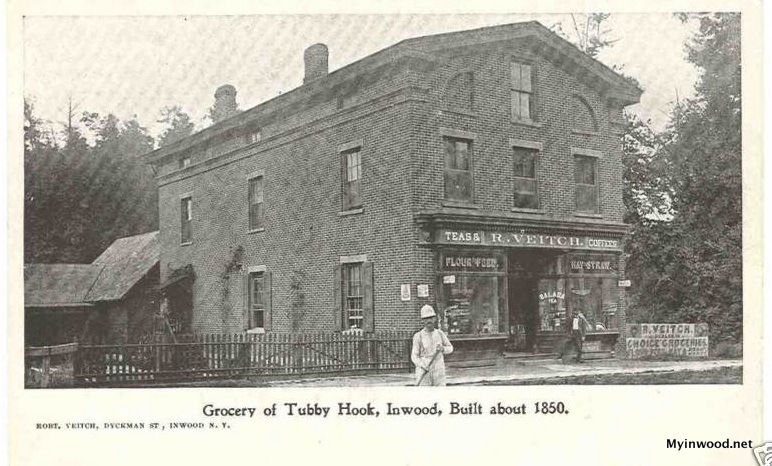

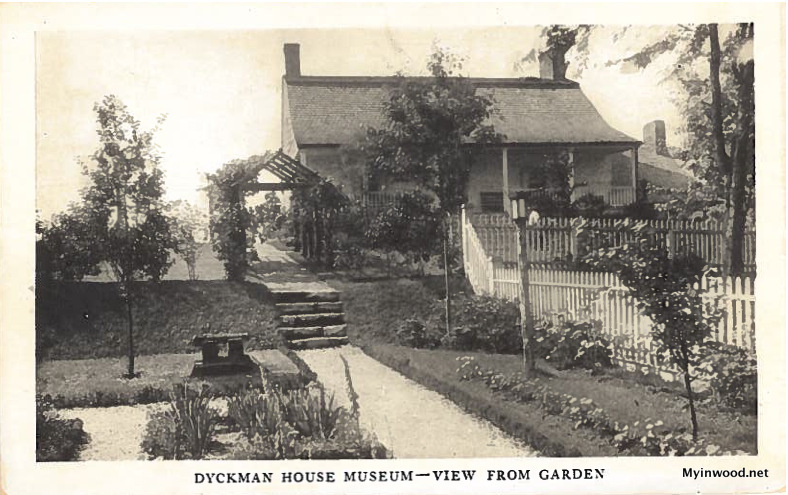

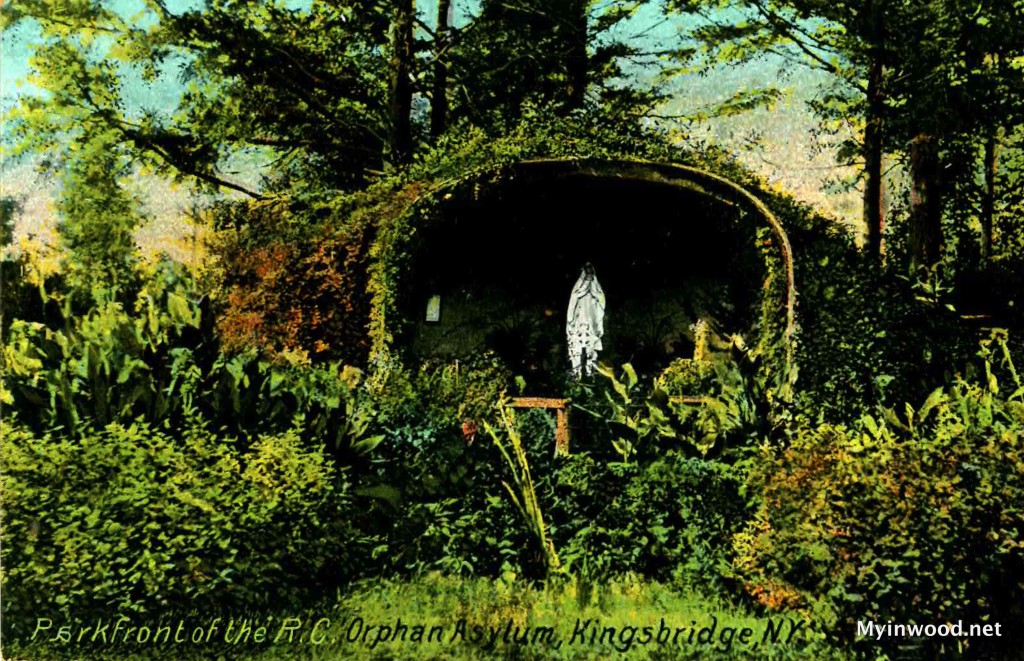

The most interesting of these structures was the “Century House” dating from 1735, and yet as occupied until its destruction by fire in 1904. For a while abandoned, but now given a new lease of life in a city park the Dyckman farmhouse stands at 203rd Street-an excellent example of an 18th century Dutch farm dwelling. The house was erected immediately after the close of the Revolutionary War. Somewhat more modern than the Dyckman- which in its checkered career had served as a tavern-was the “Black Horse Inn” building which we remember well as standing on the westerly side of the Kingsbridge Road, at the junction of the present drive and south of Dyckman Street.

The name Dyckman Street appears to be of recent origin, for three score years ago the name “Inwood Street” applied to it; which in remoter days it was referred to as the Tubby Hook Landing Road. Old timers will recall that the appendix Landing went with Hudson River shore village appellations- a relic of pre-rail road days when river traffic cut the big figure. When we know the Black Horse it had long ceased to serve its original purpose of a road home, but it was occupied as a residence down to the close of the 19th century. It was a landmark in our early days. We failed to get a photograph of the Black Horse, but there are several good drawings of the building extant.

![Black Horse Tavern, sketch from Frank Leslie's Sunday Magazine, 1884.]()

Black Horse Tavern, sketch from Frank Leslie’s Sunday Magazine, 1884.

At the present junction of Nagle Avenue and Broadway there stood a rather diminutive, but ancient, dwelling on the easterly side of the road. This little dwelling, to the rear of which was a little stretch of farmland and an orchard, shows up just within the scope of our view taken in 1892. About one year previous to the taking of this view the post-Revolutionary oak trees covering the westerly side of Laurel Hill was cut away. Some stumps of those trees may be seen in the photograph.

At a point about a 100 yards south of the little dwelling, just referred to, there stood on the same, easterly, side of the road a picturesque residence without a history it is time, yet entitled by its age and character to some consideration. Here lived a generation ago, a rather old man- John Sowerby by name, and in the early 90′s there lived with him his mother who claimed to be about 90 years of age. Mr. Sowerby told us that he had it from his forbearers that the home was erected during the yellow fever scare which he thought was about the year 1798. Perhaps it was.

![Sowerby Cottage, 1923, NY-HS.]()

Sowerby Cottage, 1923, NY-HS.

Mr. Sowerby was profuse in his recollections of northern Manhattan, but he seemed disposed to dispel the glamour of antiquity gathering about the locality-he asserted that-his mother witnessed the construction of the Black Horse Inn, and we find that a journalist writing at the close of the third quarter of the 19th century had it that the Inn was actually built in 1805, by one Henry Norman.

Most interesting of Mr. Sowerby’s “recollections,” although it was unconsciously such, was his persistent reference to his locality as the “Barrier Gate;” for strange to say he knew nothing of the barrier, or “stockade,” erected by the British across the roadway in 1779, to impede a passable irruption of an American force coming down from the north. Here was a remarkable persistence, locally of a name for above a country after the original of an appellation had ceased to exist. Remindful of that very barrier is a massive wrought iron point-part of a cheval-de-frise – found recently near the site of the British obstruction

![12 mile marker from old slide. (Now located at the Broadway entrance to Isham Park)]()

12 mile marker from old slide. (Now located at the Broadway entrance to Isham Park)

In the days of our earlier outings about Inwood there stood by the roadway two of the ancient milestones; these were the 12th and the 13th indicating the distance from “N York.” The 13th milestone which stood on the west side of the Kingsbridge Road near the extreme north end of the island has disappeared, but the 12th milestone still remains- built into the retaining wall at the Isham Park entrance. We were told that the stone originally stood at the 203rd Street corner; the present pitted appearance of the stone is attributable to a shotgun charge fired by a hunter who wished to empty his piece on the return from a hunt.

The roadside fences, the ancient dwellings, and the milestones were the features that gave character to the stretch of the old Kingsbridge Road as we knew it in our early pilgrimages thither.

![Reconstruction of Hessian hut behind the Dyckman farmhouse.]()

Reconstruction of Hessian hut behind the Dyckman farmhouse.

One hundred years after the close of the Revolutionary War the fields and heights of Inwood yet reeked with reminders of that struggle; and while it was not literally true as Lossing has it that there was “scarcely a road of ground thereabouts that was not scarred by the entrenchers” there were evidence on every hand of military occupation. Reminders innumerable of the British military possession turned up when the soil of the fields was disturbed by tillage-or was loosened by the frost or rains.

![Dyckman House. Hessian Hut being built by William Calver and and Reginald Bolton in 1916. Dyckman House. Hessian Hut being built by William Calver and and Reginald Bolton in 1916.]()

Dyckman House. Hessian Hut being built by William Calver (standing with straw hat) and and Reginald Bolton (far right) in 1916.

In the course of repeated visits, in season and out of season, we gathered up these mementos, and in time we retrieved inscribed bits of accouterments traceable to each and every corps of the enemy serving at New York. Ultimately we located the campsites of the British and Hessian armies, and these several camps have been, or will be, duly described by me.

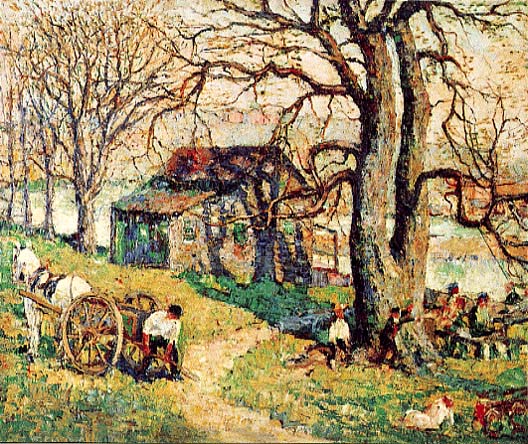

![Hut Camp of the 17th Regiment on Inwood Hill, NYC, by John Ward Dunsmore, 1919.]()

Hut Camp of the 17th Regiment on Inwood Hill, NYC, by John Ward Dunsmore, 1919.

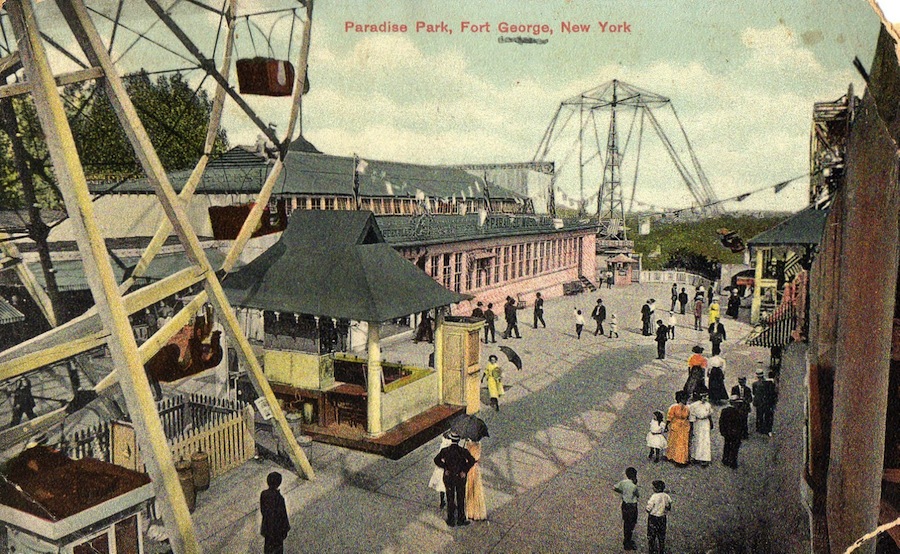

Three campsites distinctly British, and one camp occupied by Hessians were discovered and explored. The British sites were the camp on the northerly side of Nagle Avenue at the junction of the avenue near Broadway, a camping place on the west bank of the Harlem River on the line of 201st Street, and an extension hut camp at Payson and Seaman Avenues, in the vicinity of 203rd Street, west of Broadway; the Hessian camp was that of the Lieb Regiment, or “Body Regiment” – located at Arden, and Thayer Streets east of Broadway. Other camps were at Fort George at 192nd Street, and Audubon Avenue – and at Fort Washington; but these, like the camps of the valley, are subjects for separate papers.

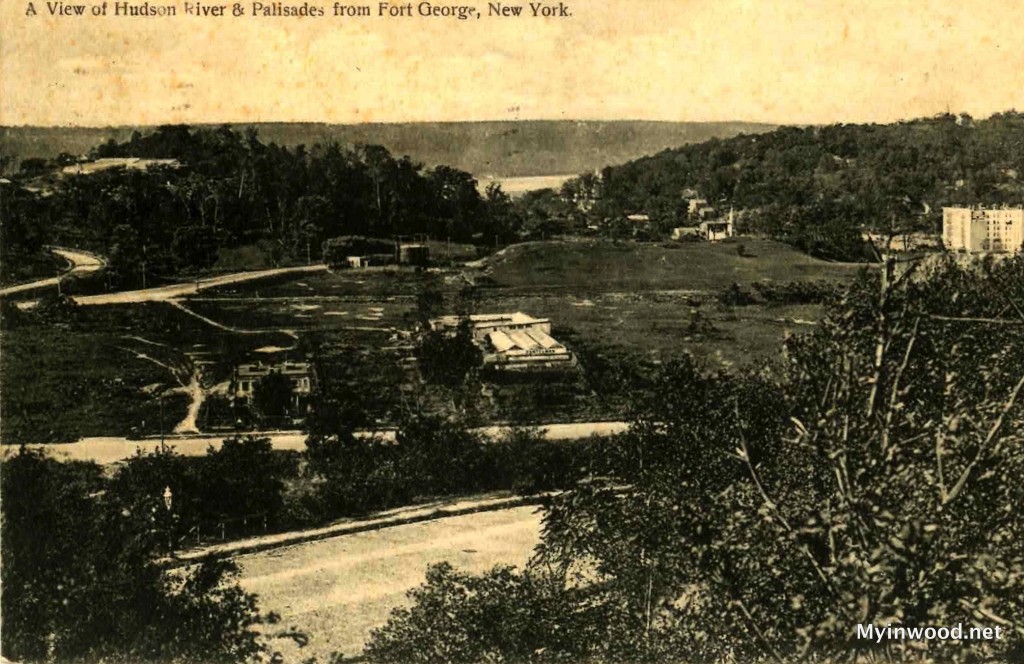

![Turn of the century view of the Inwood Valley looking north from Fort George before real estate development transforms the landscape, NY-HS.]()

Turn of the century view of the Inwood Valley looking north from Fort George before real estate development transforms the landscape, NY-HS.

![Inwood Valley in 1910 looking north from Fort George, notice construction boom underway, NY-HS.]()

Inwood Valley in 1910 looking north from Fort George, notice construction boom underway, NY-HS.

The Inwood valley as it appeared forty years ago is shown completely on the photograph which the writer had taken at that time, and which is, we believe, is unique in its way. For these were in the last days of rural Inwood to apprehend its early passing. A study of the view will convince the reader of the probable truth of a story current in Inwood long after the alleged visit of the city newspaper reporter, that a legitimate excuse of a tardy schoolboy, at the public school, was that he was delayed by his driving of the cows to pasture.

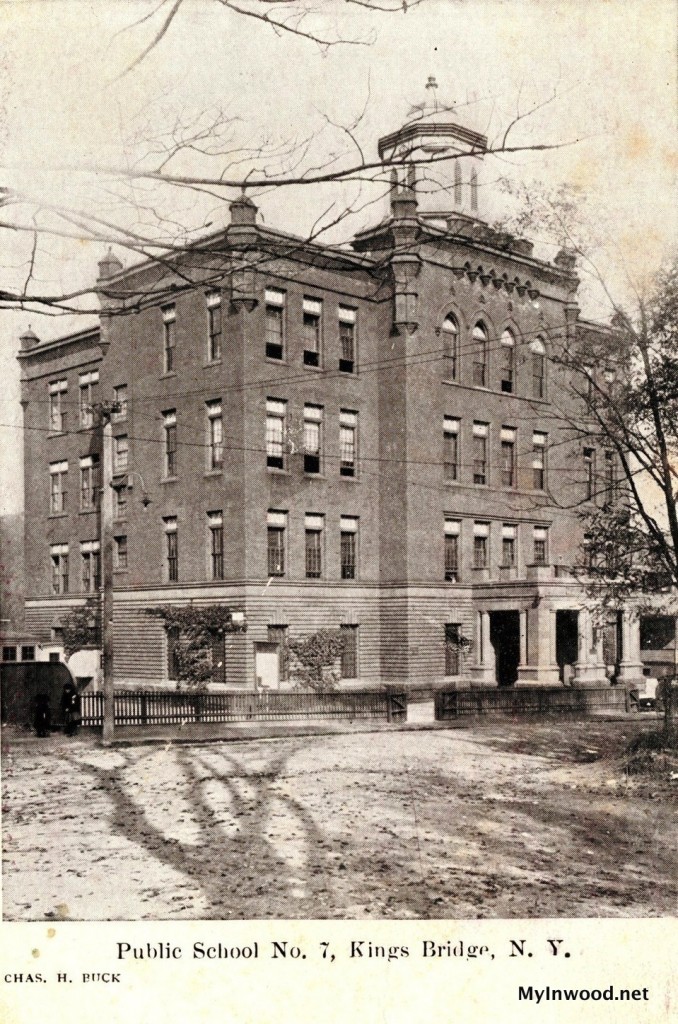

!["Ward or Public School No. 52 was a landmark on the southeast corner of Broadway and Academy Street from 1858 to almost 1957. This picture dates from about 1902, or midway of that period. Note the gas lamp with a mailbox on the lamppost. At the right is the house where the caretaker lived." -Source- William Tieck, Schools and School Days.]()

“Ward or Public School No. 52 was a landmark on the southeast corner of Broadway and Academy Street from 1858 to almost 1957. This picture dates from about 1902, or midway of that period. Note the gas lamp with a mailbox on the lamppost. At the right is the house where the caretaker lived.” -Source- William Tieck, “Schools and School Days.”

The school-building-with its fourteen chimneys, is still standing and doing duty as a schoolhouse. It may be seen on the eastern side of Broadway, at Academy Street, in one view taken in 1892.

![Ship Canal Bridge in 1907, NY-HS.]()

Ship Canal Bridge in 1907, NY-HS.

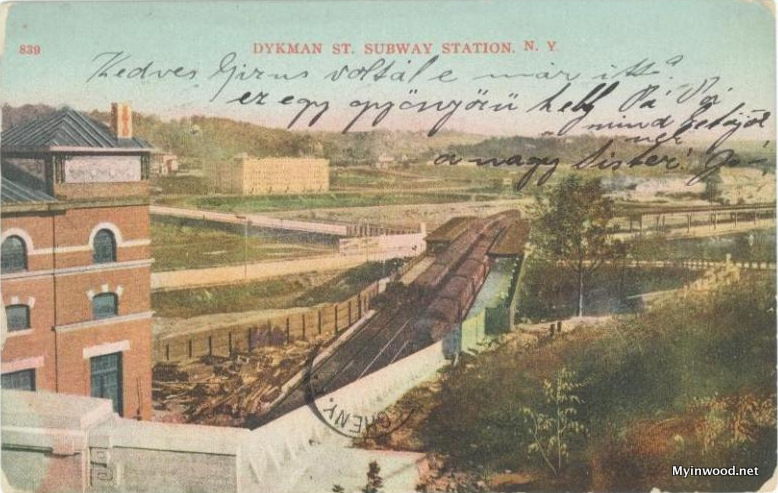

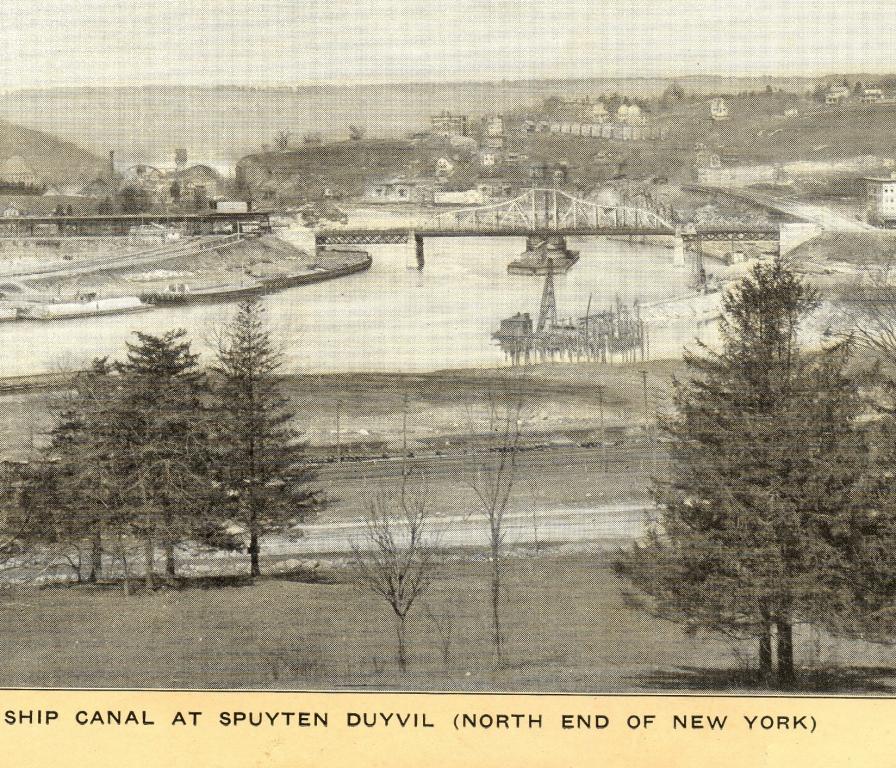

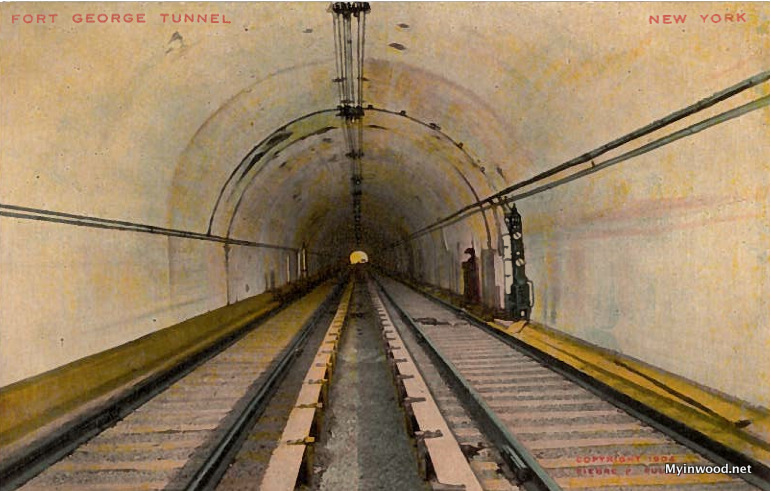

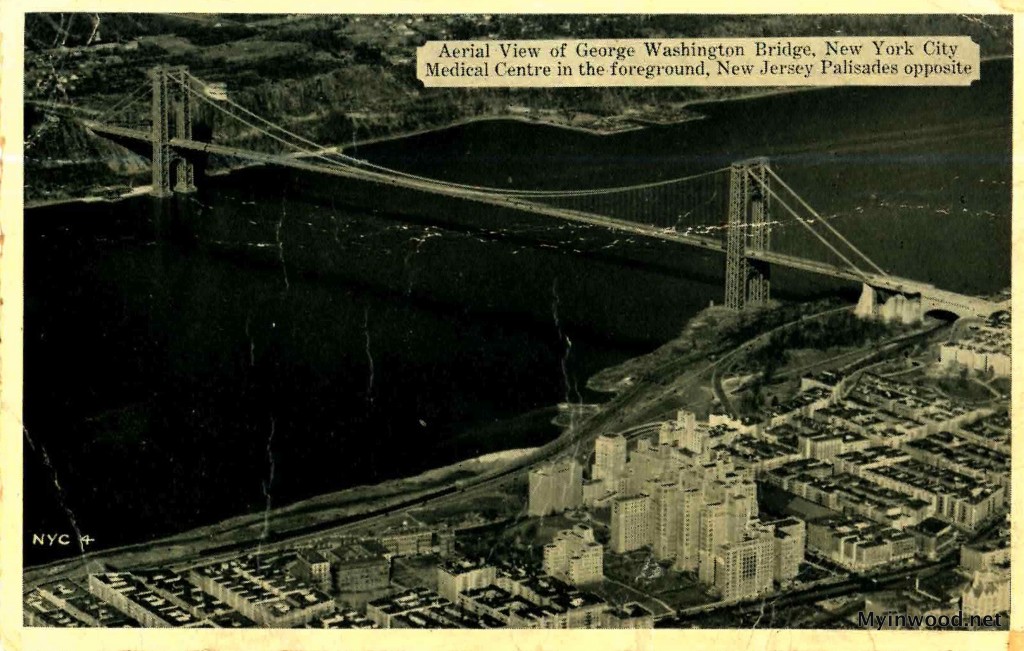

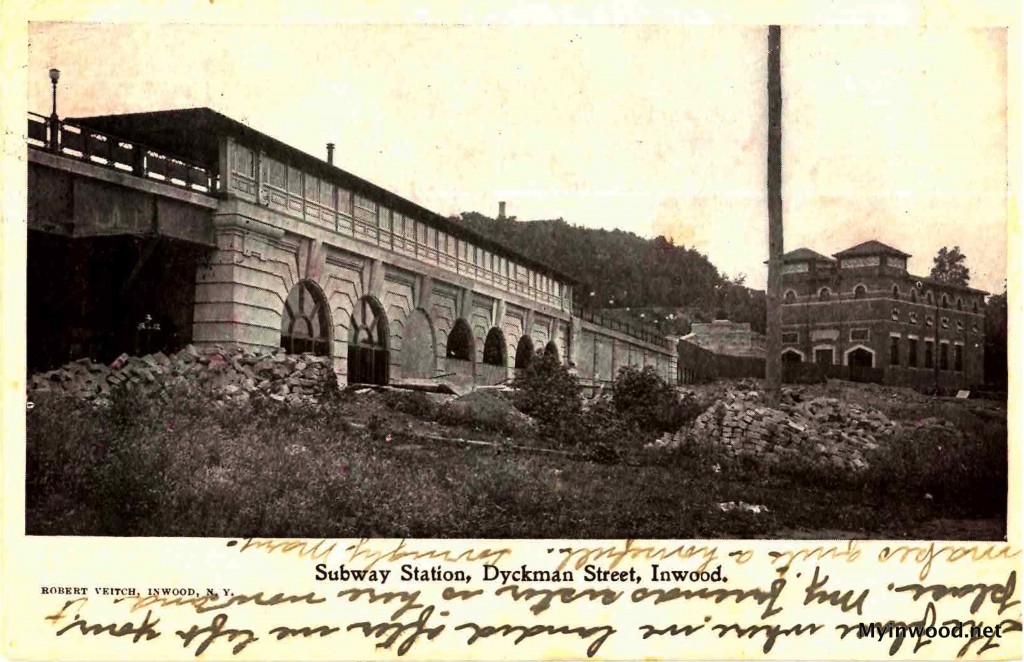

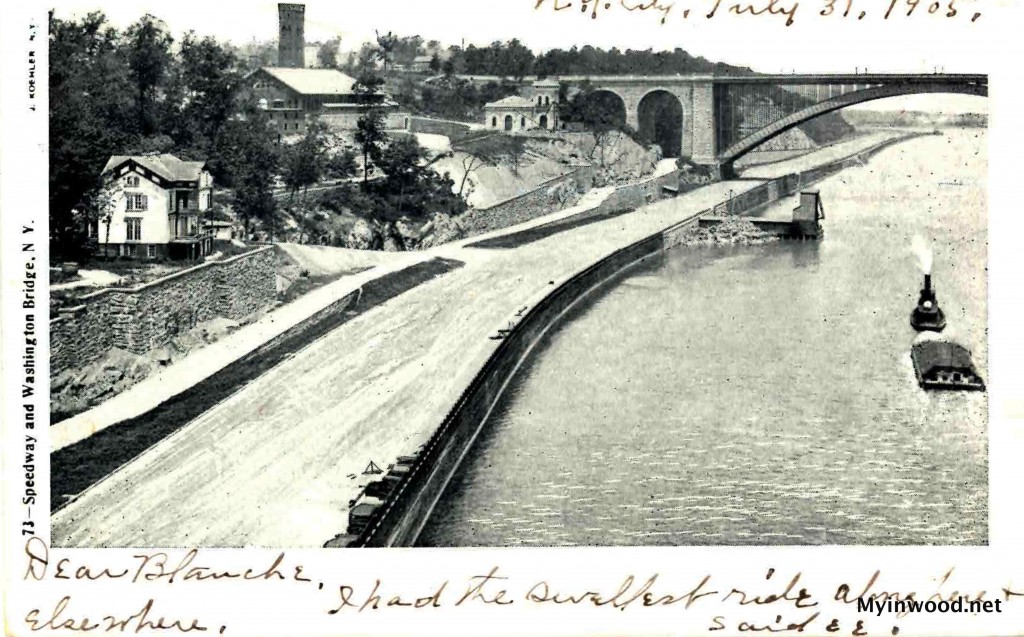

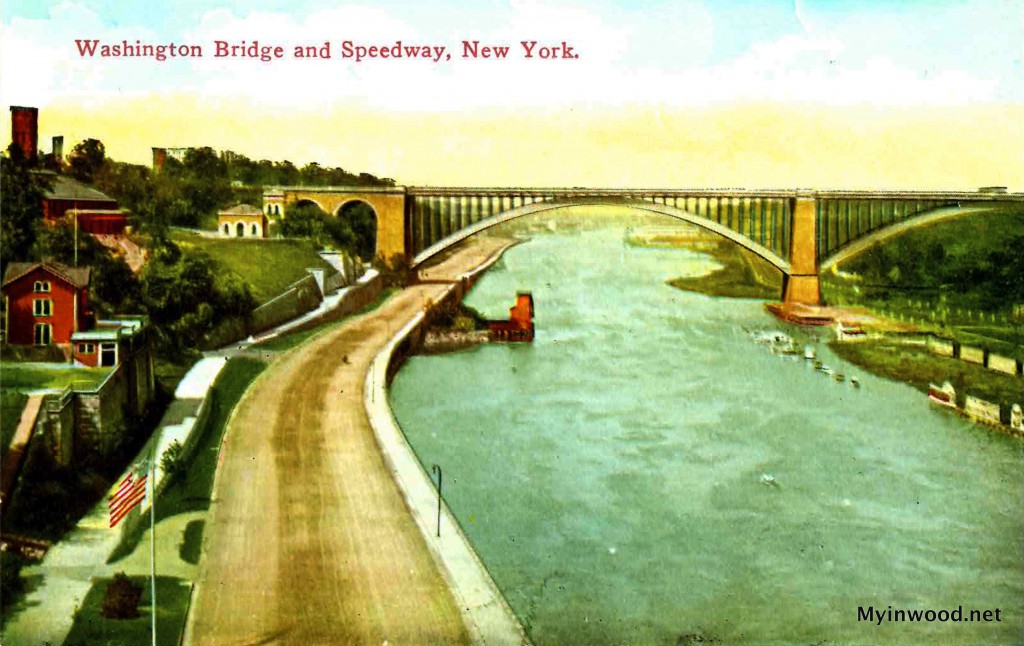

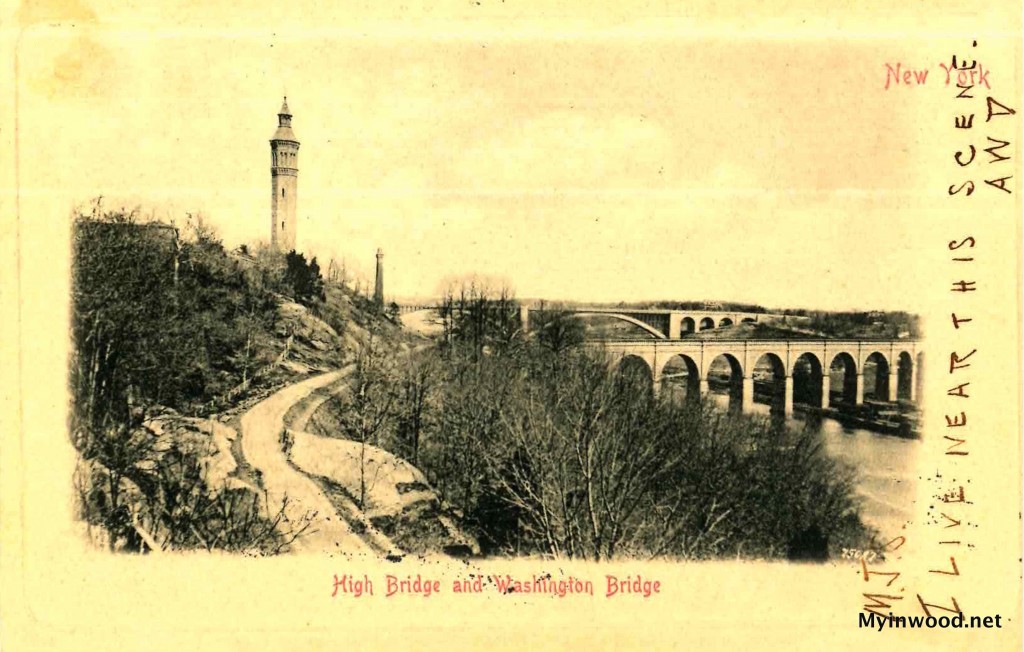

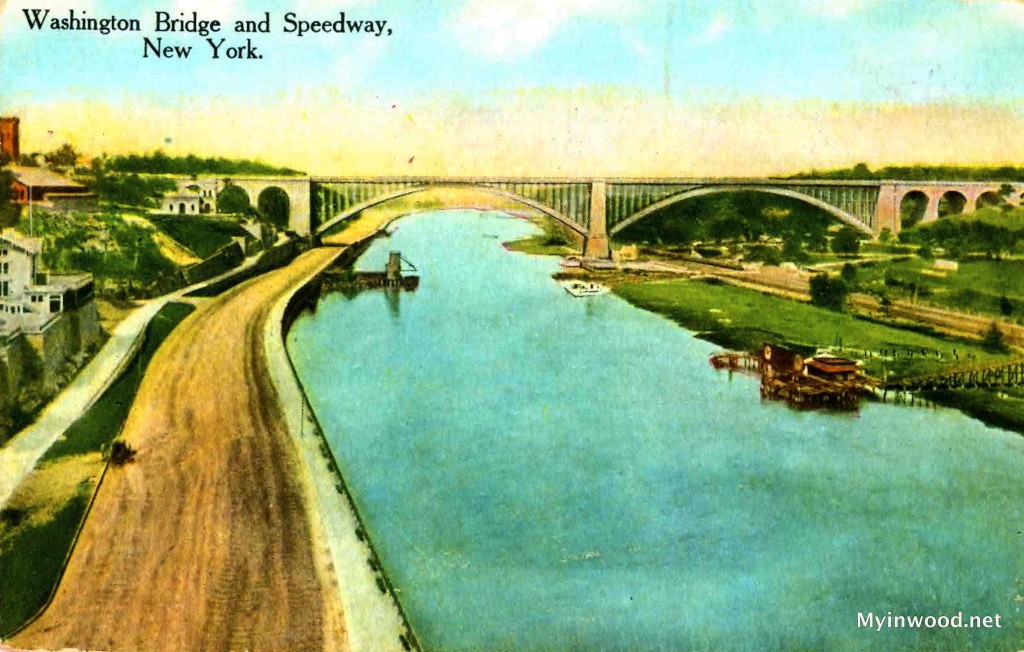

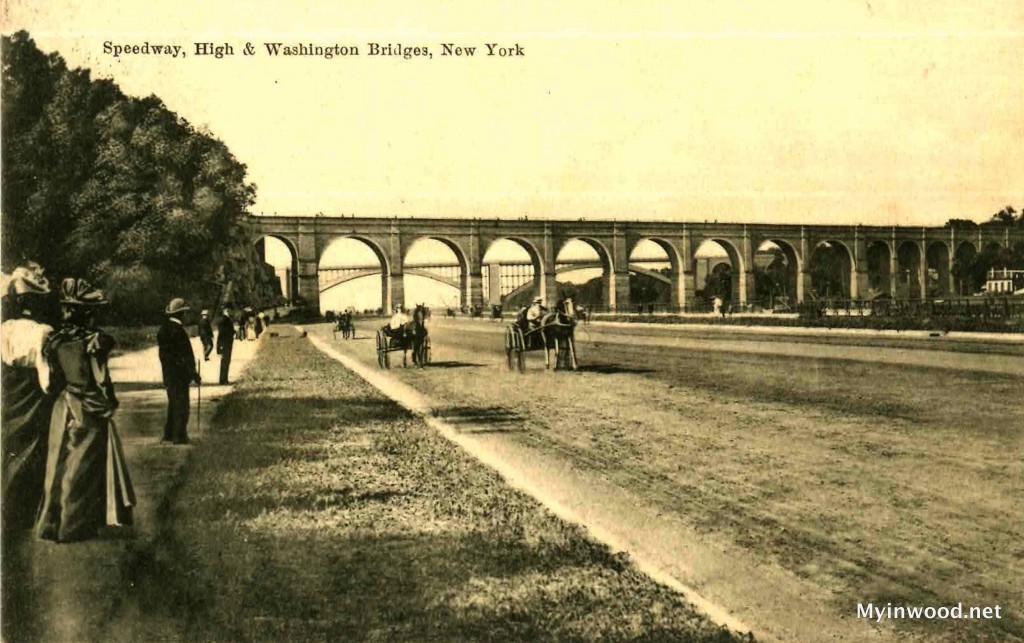

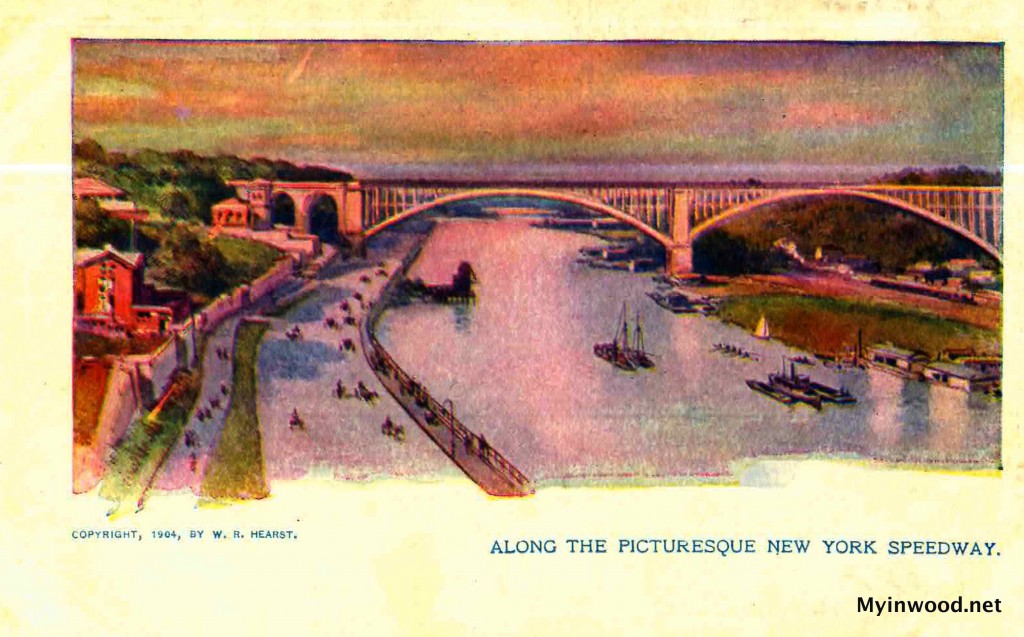

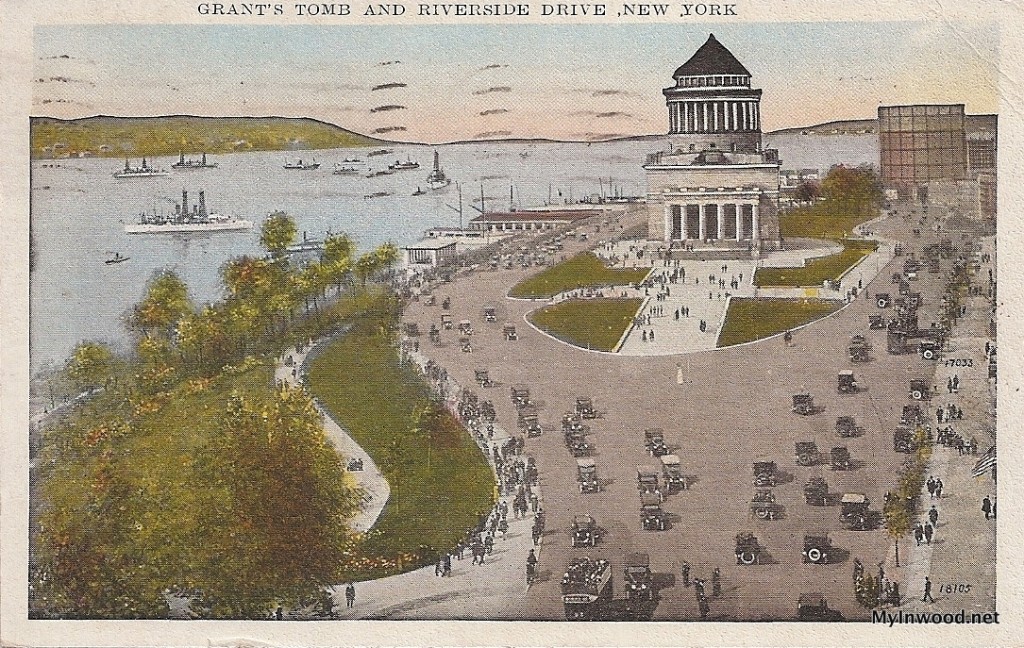

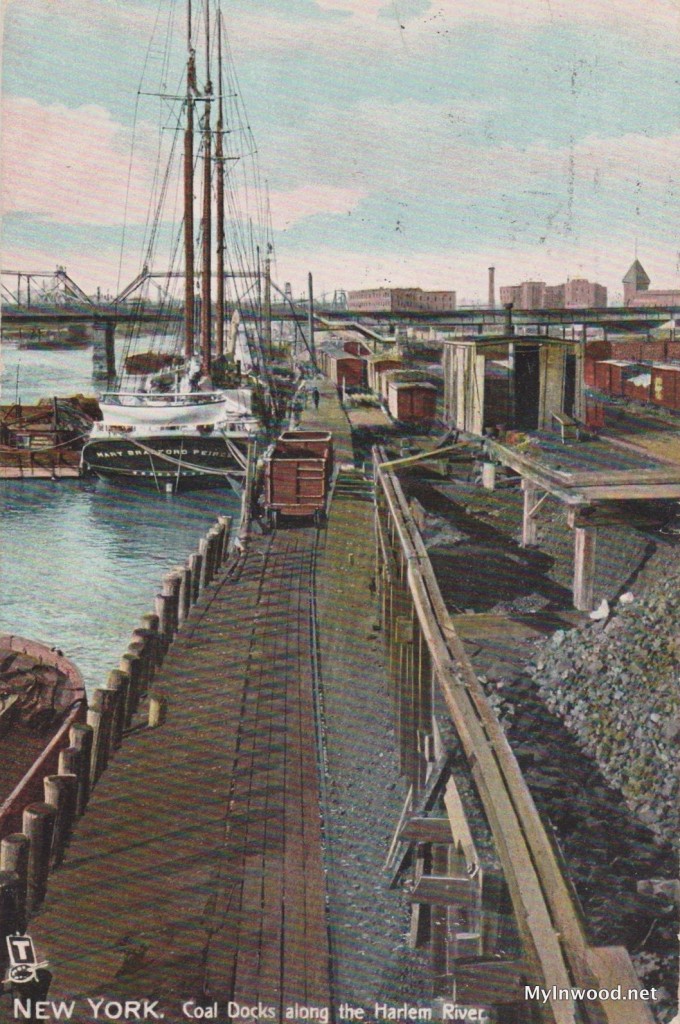

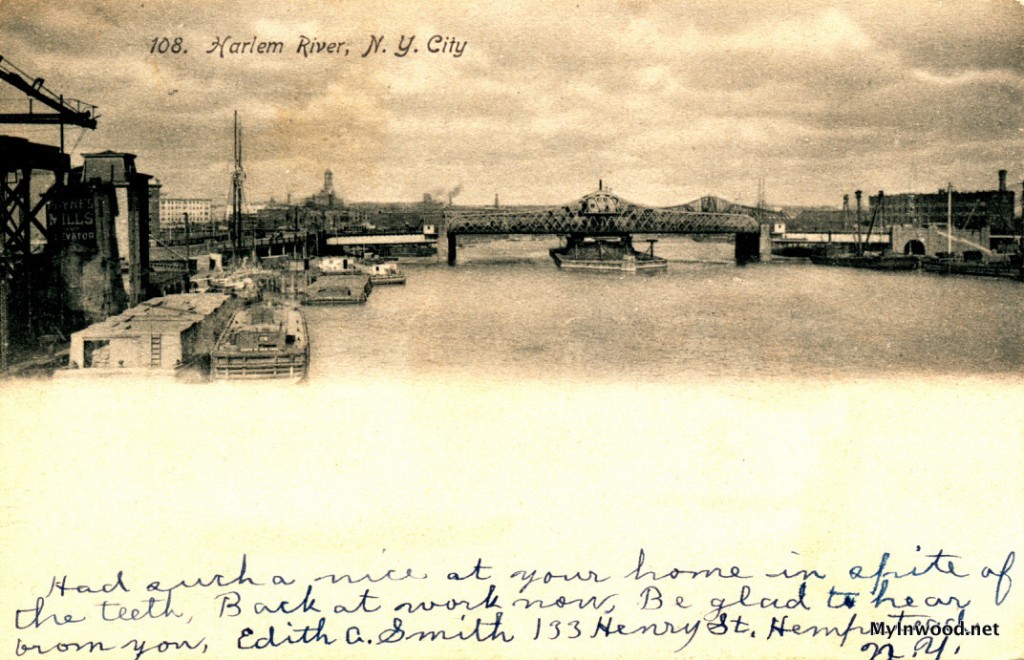

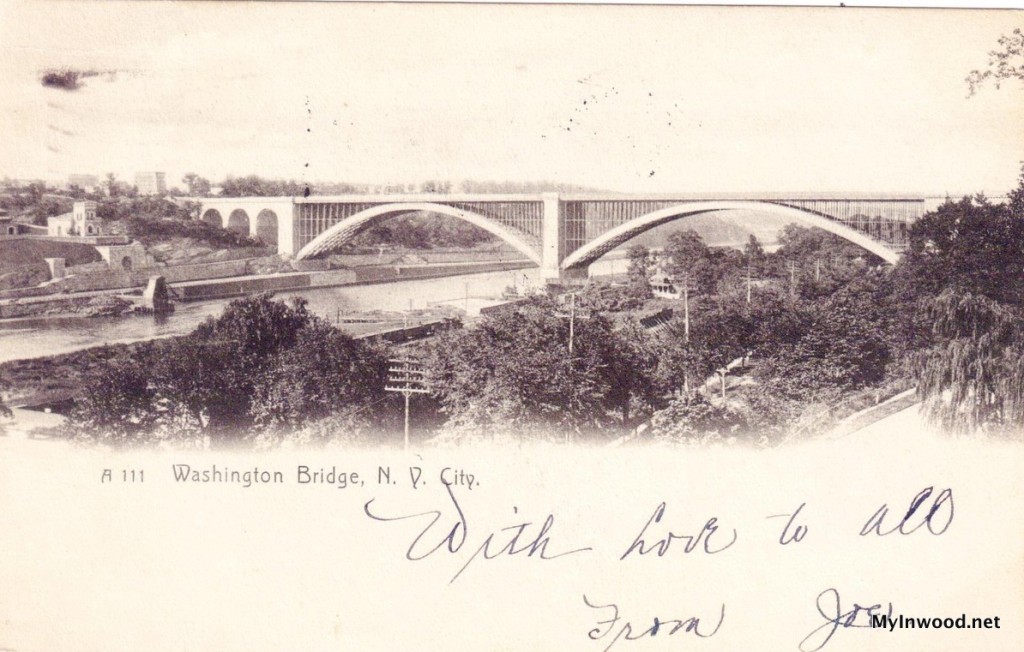

We have referred to the Kingsbridge which was built towards the close of the 17th century and was named for King William III; and mention has been made of the Dyckman’s Bridge or the Free Bridge built in 1759 to compete with Kingsbridge and removed in 1911. These structures served their day, but passed out with the coming of the subway which opened for business in 1907. Spanning the Harlem there was another bridge which connected the Inwood district with Fordham until 1907 when it was replaced by the present 207th Street Bridge-which by way was originally erected over the Ship Canal, on the line of Broadway, at 221st Street, and upon the instillation of the present two story bridge, over the canal, was floated down to its present site at 207th Street.

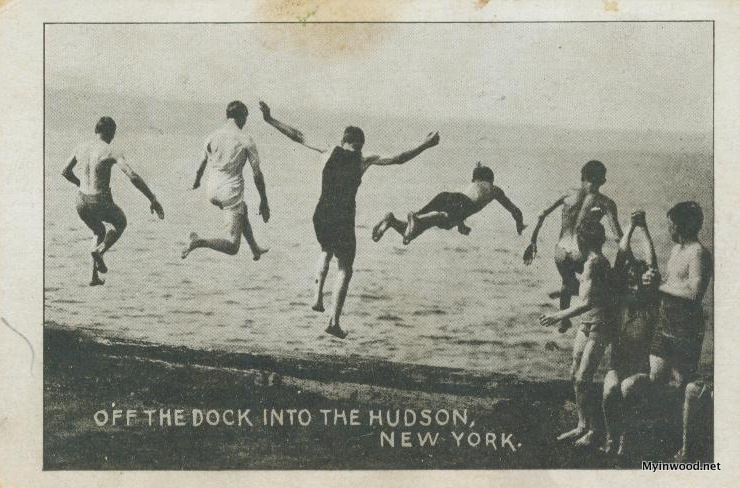

![Inwood's Floating Bridge, 1906 Inwood's Floating Bridge, 1906]()

Inwood’s Floating Bridge, 1906

The footbridge to Fordham was never a very substantial affair. The structure consisted of a narrow pathway of planking supported upon small piles barely high enough to clear the floating ice at a very high tide. The boys resorted to it as a bathing pier, and in the crabbing season the pedestrian had to pick his way through the assemblage of crabbers. In the period just previous to the coming of the present bridge the trestle bridge and causeway part of it were in an advanced stage of dilapidation. We recall that at the last the forehanded foot passengers brought with him a plank to stop a probable gap in the causeway while other passengers restored a missing span with a plank taken from a section of the pathway they had already passed. Towards the close of its existence the bridge was resorted to only in cases of extreme need; and on a windy day only the venturesome made use of it.

Along the Harlem River on its westerly side were many coves and inlets. One of these coves had been obliterated-probably in Colonial days by the construction of a dike paralleling the river at 211th Street. Some thrifty Dutchman of the 17th century had perhaps, by the erection of this embankment eliminated a goodly stretch of “waste-land” – purely city owned under the Charter of 1686, and had given a homelike look to his buildings, certainly remindful of the land from which he sprang.

We found the stretch of high ground bordering the Harlem, to the north of 201st Street, referred to as “Huckleberry Island.” We gathered a few huckleberries there, but in our time the tract was not of an insular character, though we conversed with an old resident who asserted that he had rowed around the “island” at a very high tide.

Some discussion, we understand, has arisen in recent years regarding the legal ownership of what is now solid ground bordering on Sherman’s Bay or “Creek.” There were those around Inwood half a century ago who habitually referred to the present existing inlet as Sherman’s “Bay”-it was in early times the “Half Kill.” The name “bay,” we take it, should apply to that stretch of water affected by the tides, and the appellation “creek” to that tributary-formerly known as “the Run”-which had its source west of Broadway just south of 181st Street. It might be said to have emptied into the bay at the present junction of Nagle Avenue, and Dyckman Street, but previous to the filling in of Dyckman Street in 1892-even at low tide one in coming down from Fort George to a point where the subway station now stands had to proceed southward nearly to the line of Arden Street in order to pick his way dry shod – using stepping stones at times -to cross the creek and reach the fields of Inwood. On our way we gathered wild iris blooms at Thayer Street, and Nagle Avenue-at the mouth of the creek. In Revolutionary days the creek was apparently navigable at times along the line of the present Nagle Avenue, as far as Broadway; for it is so recorded by Von Krafft, the young Hessian officer that in July 1781 many pontoons were floated up from New York and were placed in the “Line Barrier.”

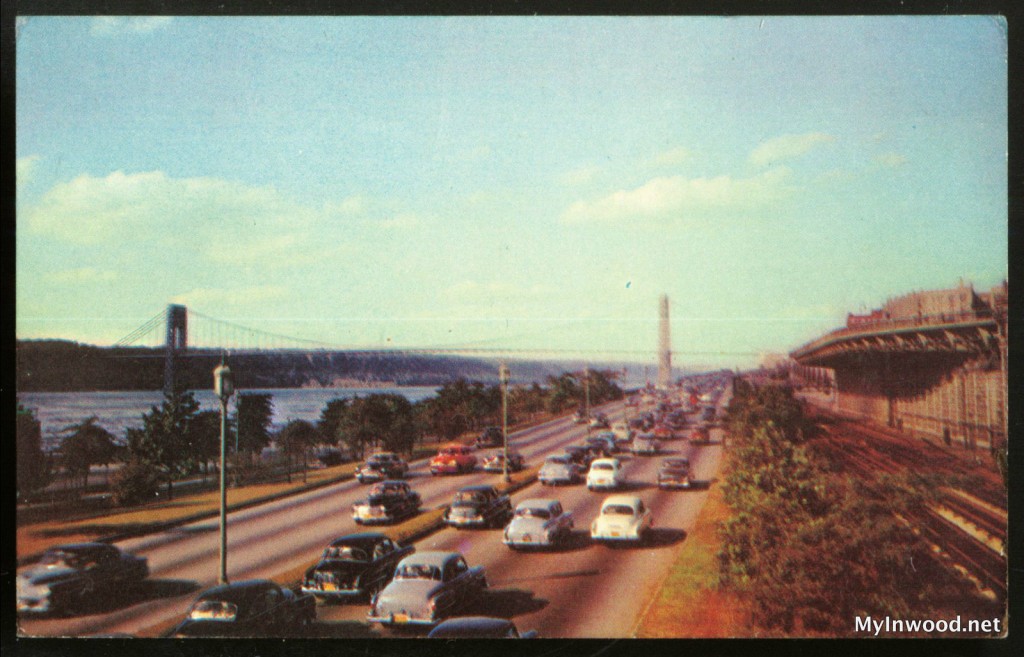

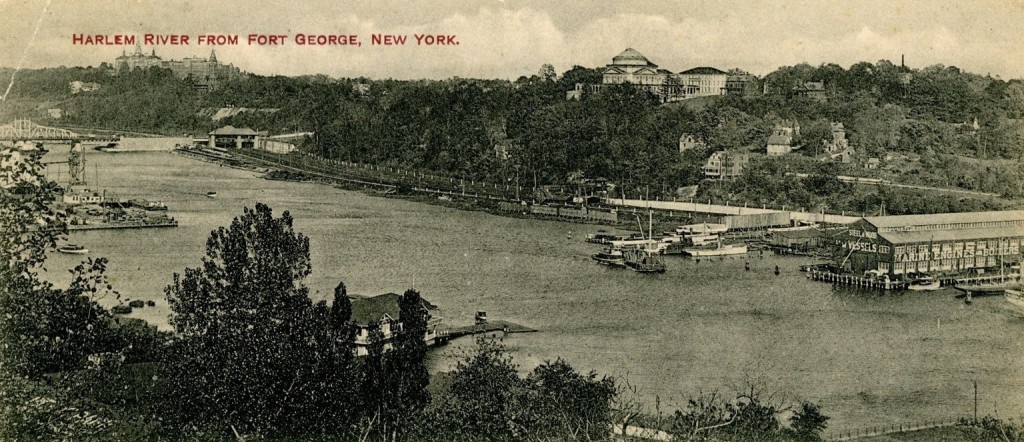

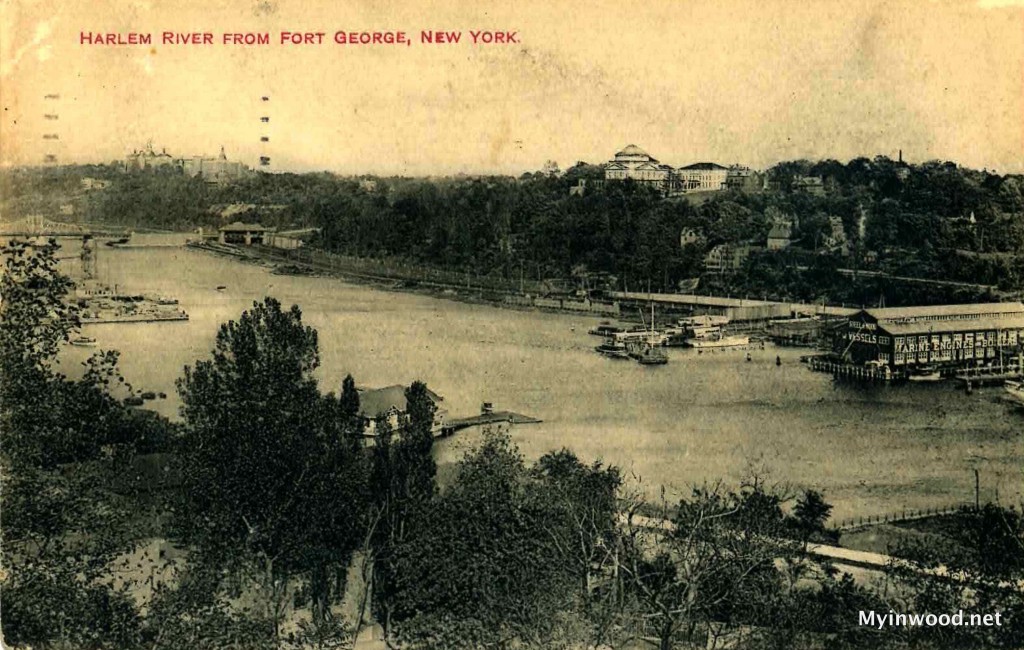

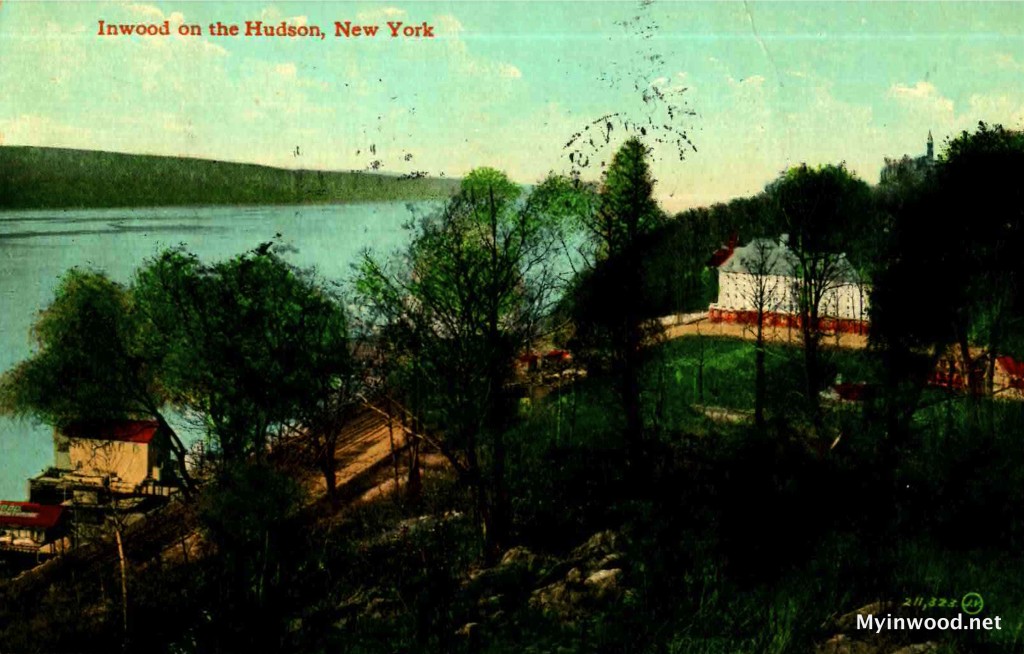

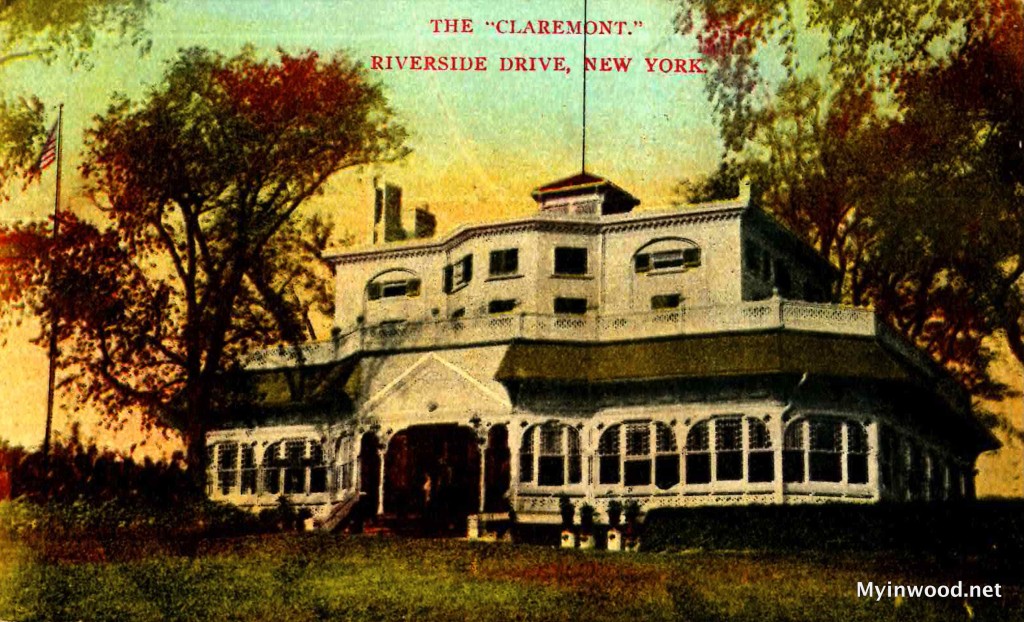

![Harlem River from Fort George, New York by publisher H. Hagemeister, 1910 postcard.]()

Harlem River from Fort George, New York by publisher H. Hagemeister, 1910 postcard.

In 1890 the swamp lands, or cat tail growth, extended in an irregular diagonal line from the junction of Nagle Avenue and Arden Street, to the junction of Sherman Avenue and Dyckman Street. On the northerly side of Dyckman Street, and extending from the present junction of Vermilyea Avenue eastward to Post Avenue the area for a stones throw northward was cattail covered in the summer, and was resorted to as a skating pond in the winter. Above at the junction of Nagle Avenue with Dyckman Street on the north side of the street the Salt Meadow began, and extended then a -covering all the area between the Speedway and Sherman’s Bay-nearly to the Harlem River.

On the north side of the bay meadow of salt bay reached from Nagle Avenue to solid ground at “Bronson’s Point.” I saw a stranded barge on the east side of the Harlem about on the line of 201st Street just north on the mouth of Sherman’s Bay. There lived one Harry Bronson – who was born in the immediate vicinity. Bronson, who was a jovial good hearted sort of man, survived until a quite recent date. In his later years he lived in one of the wooden houses on Nagle Avenue at Elwood Street. At the last he was employed as a watchman in the Interstate Park. In his early manhood years Harry, with his father-picked up a living catering to pleasure seekers along the shore, and those who were fond of clams and oysters were good patrons of the Bronsons-the elder Bronson, and Harry his son. In a complimentary way the locality of the barge was referred as “Bronsons” or “Bronson’s Point.”

The character of Sherman’s Bay, and “Creek” areas show up pretty well in the views we had taken of them forty years ago. The view taken in 1892 from the westerly side of “Laurel Hill”-Fort George Hill-looking northward, is one of the few reminders of early conditions in the “Barrier Gate” district. The other large view embraces the salt meadow area on the northerly side of Sherman’s Bay, while the smaller photograph includes within its scope nearly all of the salt meadow on both sides of the bay, and the bulkheading of the bay itself.

Moreover, the photographic view shows the filling in of the northern area while the work was in progress. Through the last two decades of the 19th century a resident of Inwood-Charles Atkins by name-regularly harvested the salt hay from these meadows. Salt hay has given way to excelsior, and some other packing materials, but in the fairly olden days the hay was universally used in shipping crude pottery and other cheap fragile products. Mr. Atkins, who still survives-lived for upwards of 50 years in the Mansard roofed house which stood until 1931 on the westerly side of Broadway at Fort Washington Avenue. For more than a decade the marsh wrens nested and the muskrats constructed their huts amongst the rushes on both sides of Dyckman Street-between Nagle Avenue and Post Avenue -after the street was filled in.

At the southwest corner of Sherman Avenue and Dyckman Street there existed a colonial burial ground which, as such, had nearly faded from memory when in 1890 we discovered in a small excavation nearby some fragments of an excellent quality of Aborigine pottery a nearby resident jumped to the conclusion that there was a connection of the pottery with the rude headstones of the burial plot and with the expenditure of much labor he unearthed a dozen or more human skeletons which were believed to be Indian; but there were some old timers residing nearby who claimed a relationship with the deceased. The presence of a Charles II sixpence in one grave and iron nails in all were not convincing, but two pairs of sleeve link buttons of Spanish coin design and dating 1771, establish the character of the remains as being of whites; and it is quite probable that the buttons were worn the apparel of a British officer-possibly a victim of the battle of Fort Washington in 1776. Such sleeve links we have found in many British Revolutionary sites. There appears to have been a voque of corn-design buttons in the 18th century days.

![Nagle cemetery Nagle cemetery]()

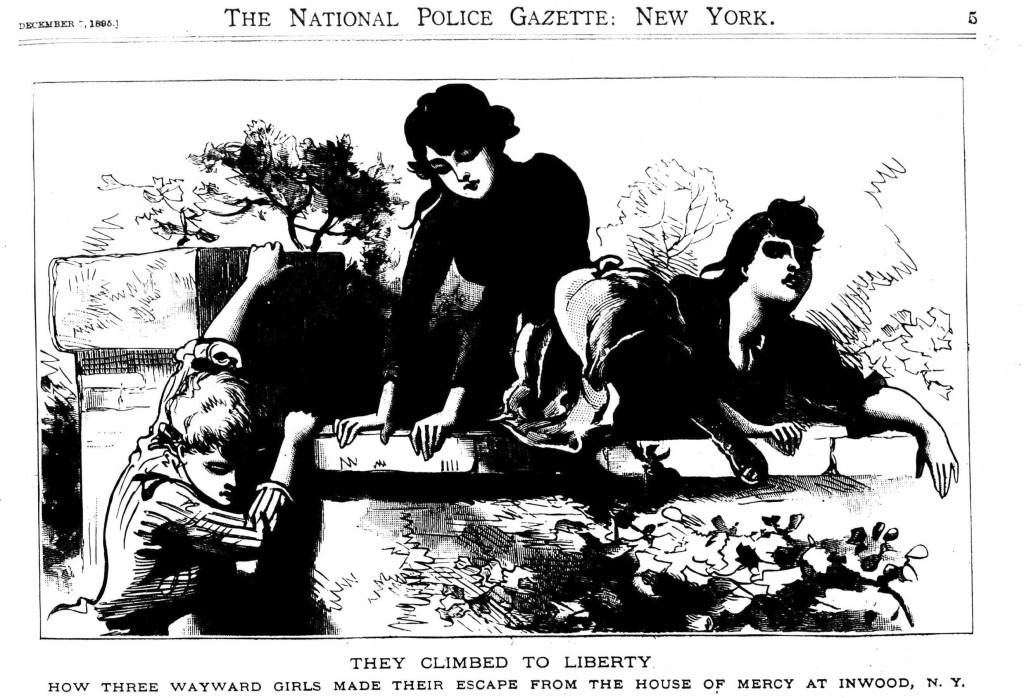

Nagle cemetery, early 1900′s

The more modern burial plot-that named for the Nagle family-we well recall-in fact it existed, though in a very dilapidated state until a recent date at 212th Street, and was graded away in preparation of the area for the new subway stops and yard. In the 80′s, and even in the 90′s, the plot was protected with a good fence, and the grounds had all the appearance of a well kept rural cemetery. Internments were made in the plot up to about thirty years ago, but with the construction of the surface railways and the subsequent opening of the subway line, a harum scarum class of pleasure seekers overran the little plot – tore down its fences and threw down the memorial stones. Before its destruction was quite complete we got an indifferent sort of photograph of the already much desecrated area of the burial plot and promised ourselves better views but failed to keep faith with ourselves in this respect. We have the satisfaction of knowing however that copies were made of all legible inscriptions upon the stones of the plot.

![Nagle Cemetery between 9th and 10th Avenues between 212th and 213th Street, 1926, NYPL.]()

Nagle Cemetery between 9th and 10th Avenues between 212th and 213th Street, 1926, NYPL.

For above a dozen years previous to the grading of 10th Avenue, along its route through upper Manhattan Island we had had our eye on a feature of the ground at 212th Street on the line of the Avenue, for there, amid a cluster of tall pear trees many rude stones, which could hardly be said to be regularly set, projected from the ground. Tradition had it, as we found, that the stones marked slave’s graves. We could never trace the origin of this report, but there certainly existed a belief that human internments had been made there, for apparently the ground had not been plowed since the placing of the stones. Our chance to verify, or disprove tradition came in March 1903 when the work of grading 10th Avenue began. In the course of grading though the knoll about thirty skeletons were exhumed. The skulls of these were examined by Dr. Herdlika, the eminent craniologist and were pronounced by him – “purely African.”

One of the skulls we photographed, and many other skulls were photographed-en masse. As indicated by the presence of nails in the grave, the bodies had been interred in wooden boxes while the presence of brass pins and the green stains thereof upon the skulls indicated that shrouds had been used. Aside from the nails and the pins the only other metallic object recovered was a brass brooch set off with brass and blue glass beads. It is well known that slavery existed in this state and was finally extinguished in 1827. On studying up on the subject of slavery we discovered some interesting matter relating to the burial of slaves. It is recorded that the English colonists were slow to act on the suggestion from the Crown to “find out the best means to facilitate and encourage the conversion of negros, and Indians to the church faith provided that the baptism of any slave should not be deemed a manumission of such slave.”

It was the custom in the old slavery days hereabouts to inter the remains of bond servants in a plot set apart for that purpose, and the law provided how simple the burial services must be. A law passed in 1722 decreed that all negro and Indian slaves dying within the City should be buried by daylight. The law was subsequently rescinded and it was decreed that not more than 12 slaves should attend any funeral under penalty of a public whipping. No pall, gloves, or favors of any sort were to be worn, and any slave who was found to have held a pall or worn gloves or favors was to be whipped. The ceremonies of slave burial must have been-in consequence of the laws-rather simple, as few probably had any instruction in the Christian faith, and whereas many of the blacks were direct importations from Africa it is quite possible that pagan rites were performed. The fear of conspiracies inspired the restrictive laws. The non Christian character of the blacks prevented burial in consecrated ground.

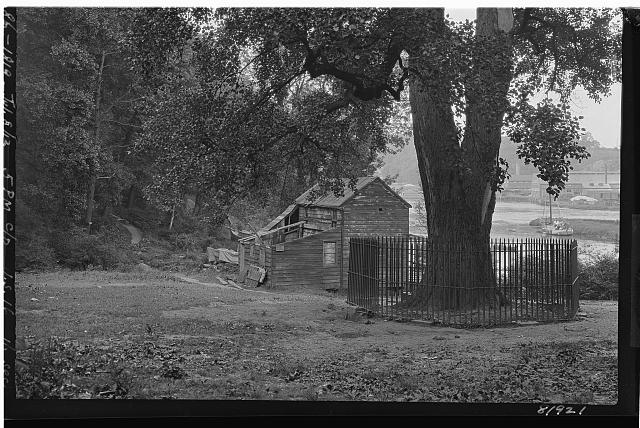

![Farming on the Spuyten Duyvil, photo by Ed Wenzel.]()

Farming on the Spuyten Duyvil, photo by Ed Wenzel.

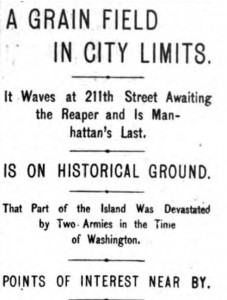

We have referred to these two local reminders of man’s mortality-white and black but in close proximity to these we had previously noted what suggested the “staff of life.” This was the last crop of grain grown on Manhattan Island, true, the grain proved to be the prosaic rye intended for the sustenance of live stock but with all that crop marked the closing of an era in the Island’s history, and was remindful of the figure which grain and products thereof had cut in the affairs of the colony. Flour and baked bread were important articles of export.

And when the growing of tobacco was found to be more profitable and thereby the price of bread soared a law was passed compelling the farmers to plant two acres of grain to one of tobacco. The flour barrel founds its place on the City seal in 1688; it is there yet. We photographed the grain field. In recent times, that is to say in the ultimate grain field days, that field was part of the Isham estate; of old it was “part of the Nagle farm.

![Century House ruins, 1904.]()

Century House ruins, 1904.

With the passing of the Nagle residence-”the Century House”-in 1904-(shown above) we got the chance we had waited for to explore the sloping ground between the homesite and the Harlem River shore.

![1904 dig at site of old Nagle homestead. 1904 dig at site of old Nagle homestead.]()

1904 dig at site of old Nagle homestead.

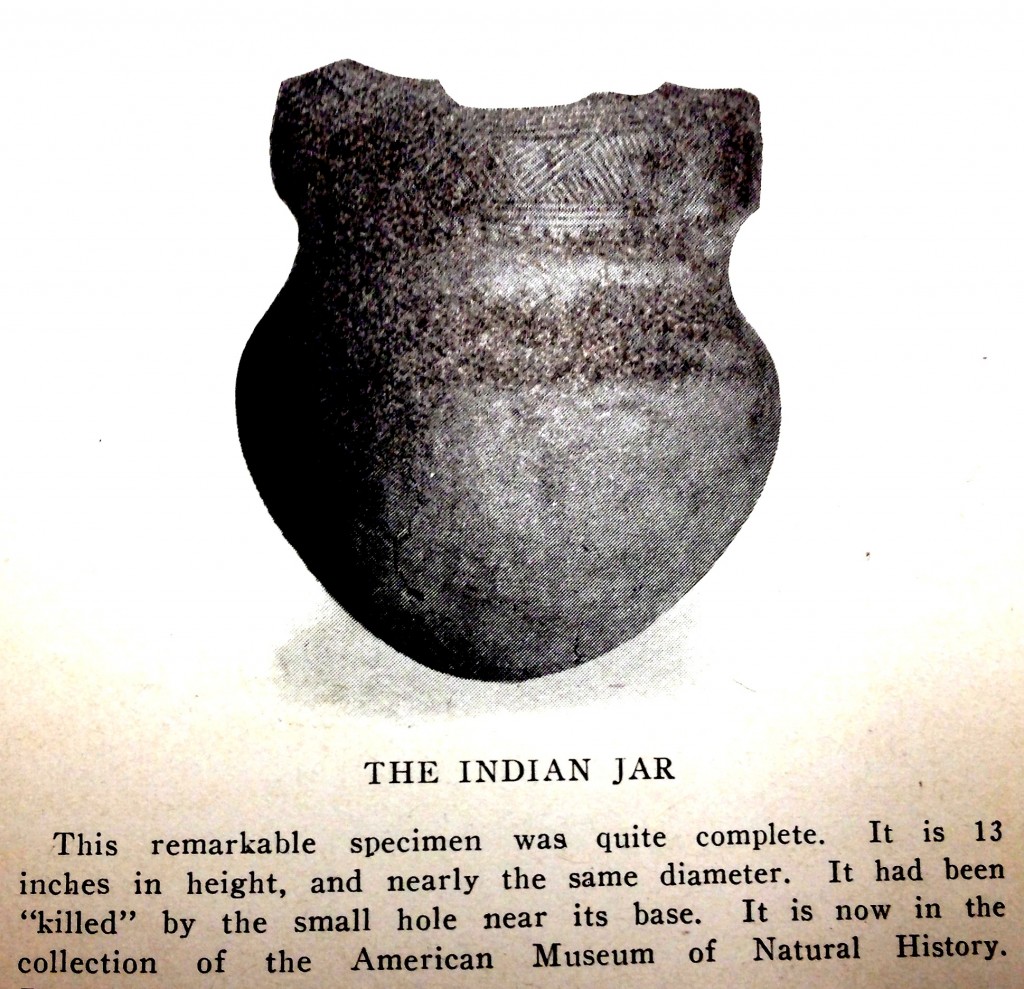

We reckoned that here would be found the discarded household and personal material of the Nagles, and mementos of the British officers who would probably have occupied the house. Our guess was good; we discovered all we could have hoped for, but in the Autumn of 1907 as we were journeying toward the subway after a days work at the Nagle dust heap we made a find conspicuous in the Archaeology of the Eastern United States.

![Native American Pottery discovered in Inwood by William Calver, Source: "Washington Heights, Manhattan: Its Eventful Past" by Reginald Pelham Bolton.]()

Native American Pottery discovered in Inwood by William Calver, Source: “Washington Heights, Manhattan: Its Eventful Past” by Reginald Pelham Bolton.

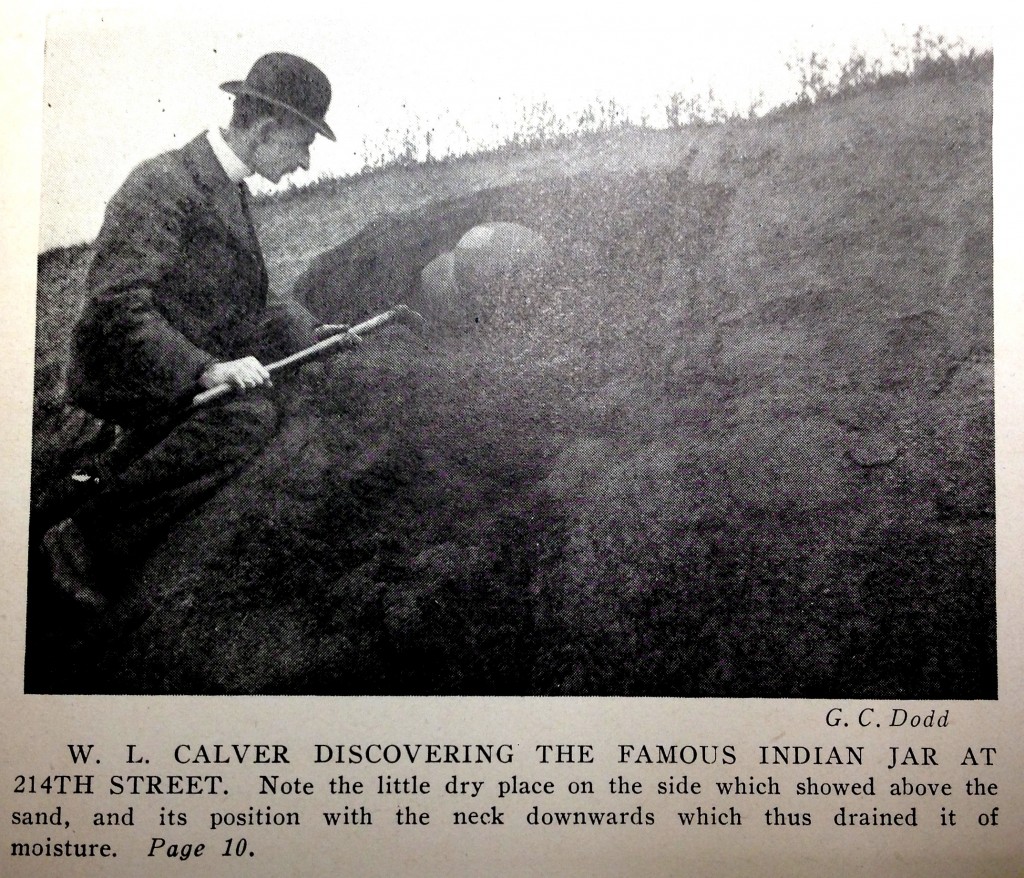

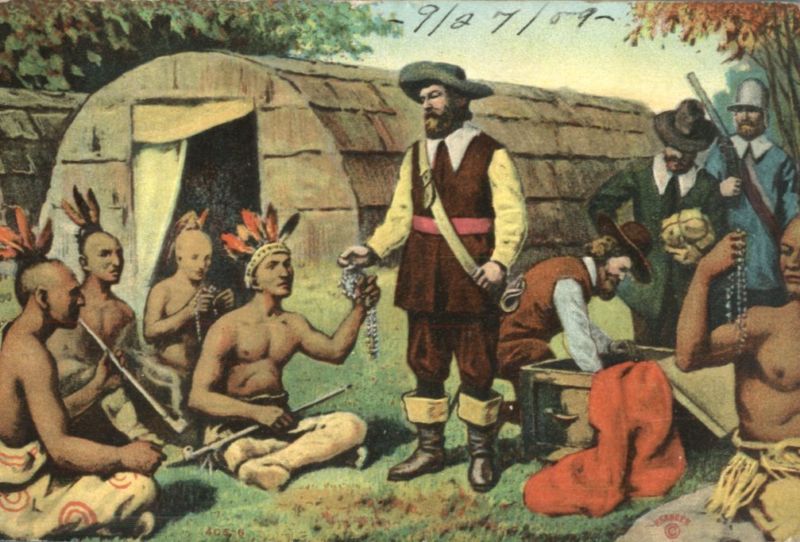

On the bankside of the newly graded 214th Street and near to 10th Avenue-right here in the Metropolis we spotted a massive and complete specimen of an Iroquoian Indian jar-the finest yet discovered. Although the pot was nearly duplicated in its dimensions and symmetry by a similar find which we made at the opening of 231st Street, we believe our first great find will never be equaled. That vessel was, miraculously barely exposed by the grading of 214th Street and was noted by us as it lay interred, just safely below the plow line, in the soft earth of the field. Probably at the departure of the last Aborigines from Manhattan Island the jar had been buried on a campsite against the day when those poor exiles would return. That day alas, for them, never arrived.

![William Calver discovers Native American Pottery in Inwood, Native American Pottery discovered in Inwood by William Calver, Source: "Washington Heights, Manhattan: Its Eventful Past" by Reginald Pelham Bolton.]()

William Calver discovers Native American Pottery in Inwood, Native American Pottery discovered in Inwood by William Calver, Source: “Washington Heights, Manhattan: Its Eventful Past” by Reginald Pelham Bolton.

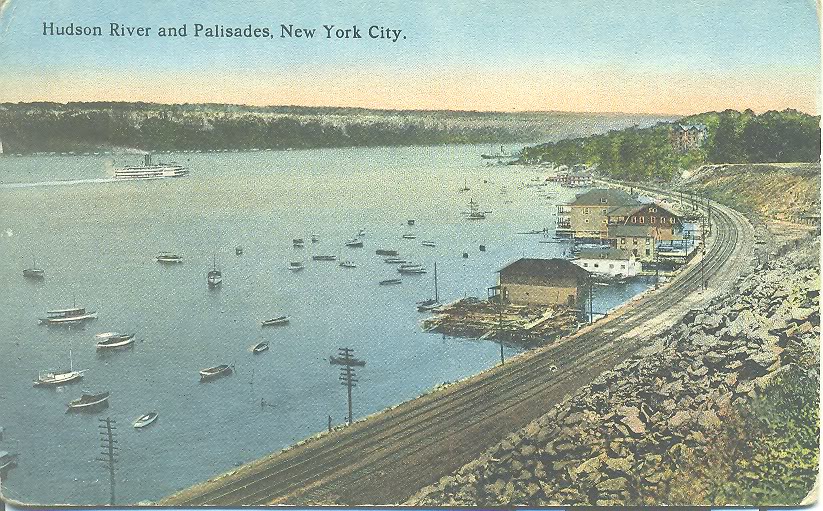

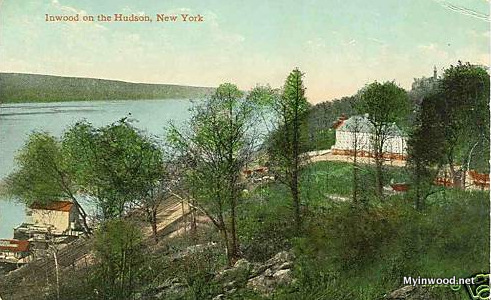

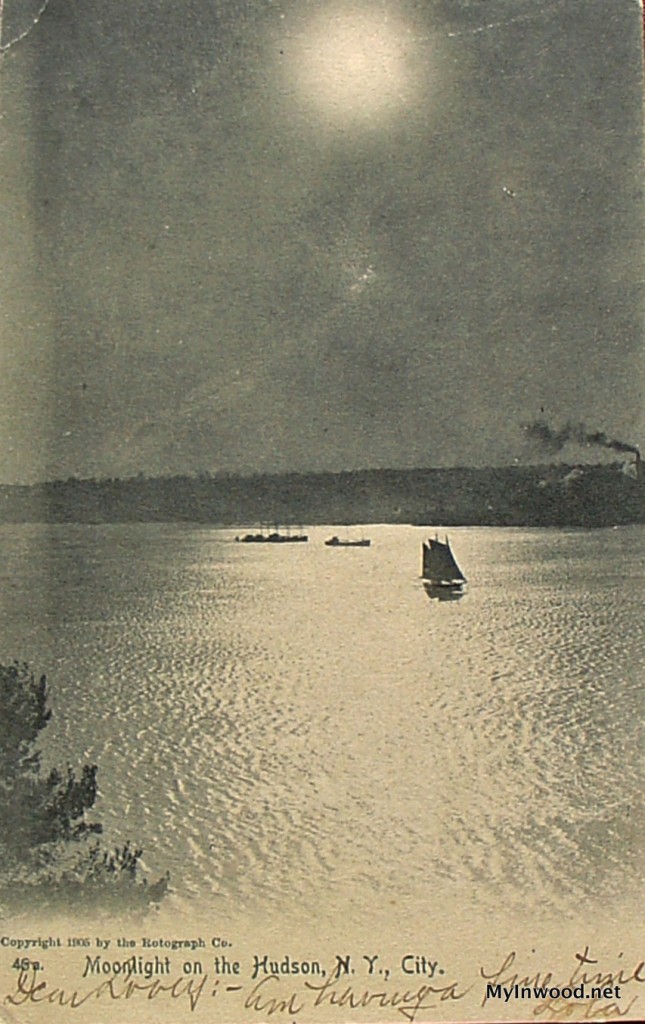

Years before that early familiarity with the region to which we referred at the commencement of these “recollections” we looked into the longing eyes over the strictly private areas of Inwood as we passed up or down on the New York Central trains. The grassy meadow bordering the Harlem and the rocky ridges to the westward appeared by us ideal in the advantages they offered to the red man whose footprint as it were-we

ultimately discovered thereabouts. It is not too much to say that with its stretches of probable Maizeland, its oyster beds, and fishing grounds; its watercourses-fowl and small game; its still waters for canoeing, along with the natural rock shelters North Manhattan was unmatchable in the features possessed for the accommodation of primitive life.

![Exploring the Indian caves Exploring the Indian caves]()

Exploring the Indian caves

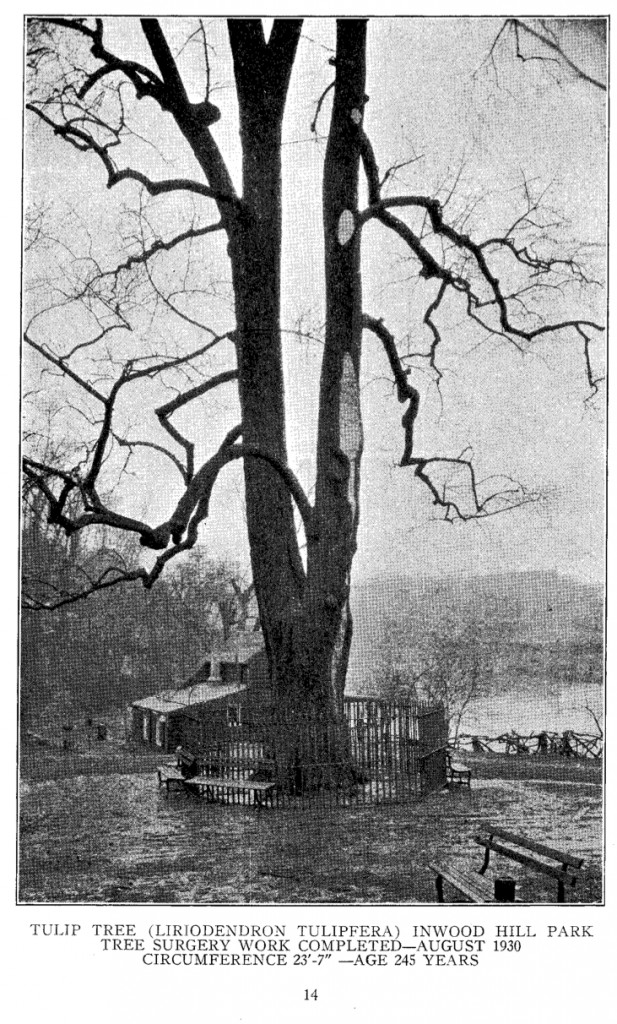

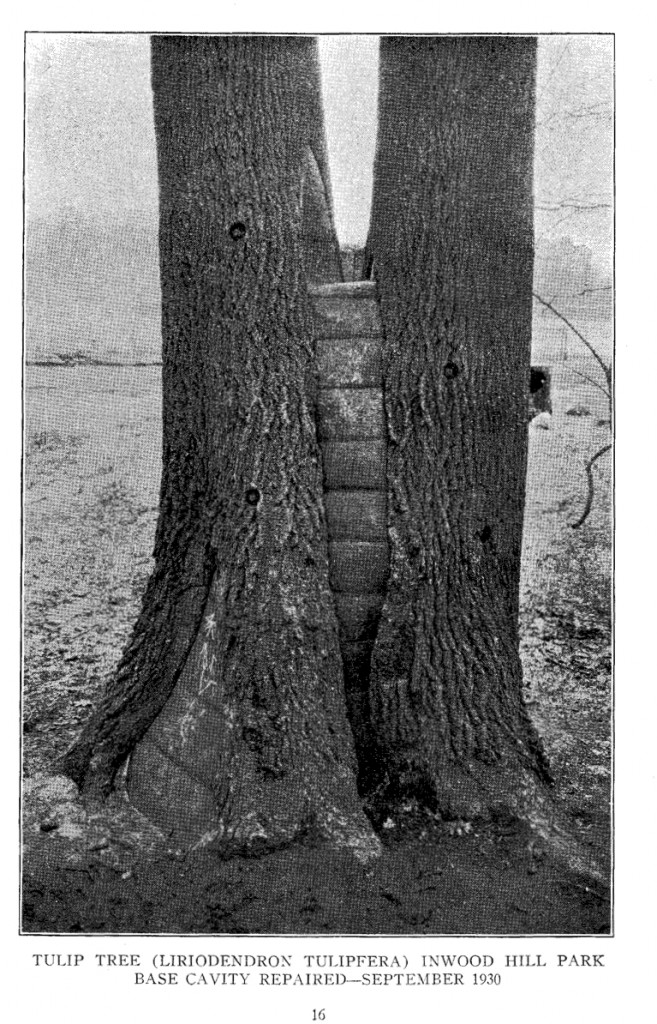

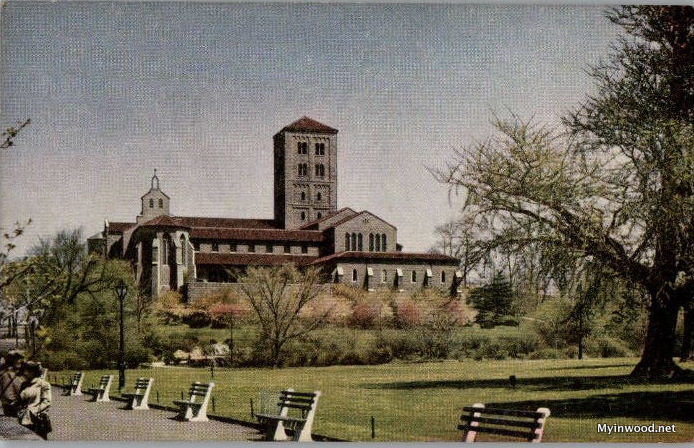

The Indian cave or “rock-shelter” now fortunately within the bounds of Inwood Hill Park, promises to be preserved-forever a memorial to the original occupants of Manhattan Island.

Doubtless the rock shelters, before the coming of the red man was the home of the bear and the wolf, and two score years ago a family of “wild dogs” that had quarters beneath some massive rocks above the Indian cave were the subject of newspaper stories for a while causing some little excitement among the residents of the valley, for those who investigated by day saw nothing, but much barking was heard in the vicinity of the rocks by night. The “wild dog” excitement never quite subsided at Inwood, and along about the year 1915 when the furor became acute all stray dogs were regarded with apprehension. The newspapers featured the matter again, so we decided we would investigate. There were plenty folks at Inwood who declared that an actual past of savage dogs existed. Hair raising stories of the nightly depredations of degenerate curs were told.

The brutes foraged at night for their rations almost to the very hearths of the, then, sparse population of the valley. Children were attacked and erstwhile faithful, home loving, dogs were lured away from regular feed, and cozy kennels, to revert to primitive conditions and a vagabond life. There was, however, some little foundation, as we found, for the stories current of dog life in the hinterland of Manhattan. To verify, or squelch the stories we fared forth and made a complete survey of the infested region, all possible natural shelters, or potential dens, were inspected, and residents of the valley, and high places, were questioned without positive results. One day as we had completed a lengthy jaunt we sat down upon a rock-one of a great mass of stones removed for the cutting of Thayer Street, and almost immediately there arose a distinct growl coming from the other rocks a few yards away. The growl was of such a volume as to convince us that it did not proceed from a lapdog. With camera in hand we retired a few paces and awaited developments. Presently one sizable puppy, and then others to the numbers of five, or six emerged from their den.

![The terrible puppies of old Inwood The terrible puppies of old Inwood]()

The puppies of old Inwood.

These puppies were exceedingly shy, but we managed to get four of them in characteristic attitudes exhibiting curiosity, suspicion, or resentment. The mother dog we may suppose was a victim of circumstances having been abandoned by her master as folks moved to other parts , she was compelled to care for herself, and resorted to such shelter as could be found as a refuge by day, while she foraged for sustenance by night. From neglect and abuse she probably developed a savage temper, and some trivial exhibition of ill will on her part may have been exaggerated to such an extent as to make her the terror of Inwood. A young man living nearby made a grand rush one day and captured one of her puppies, this puppy, we subsequently learned, grew up to be mild tempered, everyday sort of dog.

![1880's photo of Inwood Hill. 1880's photo of Inwood Hill.]()

1880′s photo of Inwood Hill.

Only a few years have elapsed since the last cow was kept on northern Manhattan, but the last actual herds of that region appear in our photograph of the Inwood farmlands.

![Last pig on Mantattan photographed on the current site of Columbia University's Baker Field, from the collection of William Calver, September 30, 1911,NY-HS.]()

Last pig on Mantattan photographed on the current site of Columbia University’s Baker Field, from the collection of William Calver, September 30, 1911,NY-HS.

The very last porker reared on the whole extent of Manhattan Island inhabited an old fashioned sty on the site of the present day “Baker Field,” near to Spuyten Duyvil Creek. The owner of the sty poured the floor of the sty with asphalt blocks expropriated from supplies for city streets , but as may be seen in our photographs this era marking animal left no stone unturned. Those who have scrutinized early drawings of New York street areas, and have recollections of the figure cut by swine in the annals of Manhattan will understand what we mean when we refer to the individual we have photographed as “epochal.”

![Spuyten Duyvil in the 1860's, note the Johnson Ironworks on the left, NYPL.]()

Spuyten Duyvil in the 1860′s, note the Johnson Ironworks on the left, NYPL.

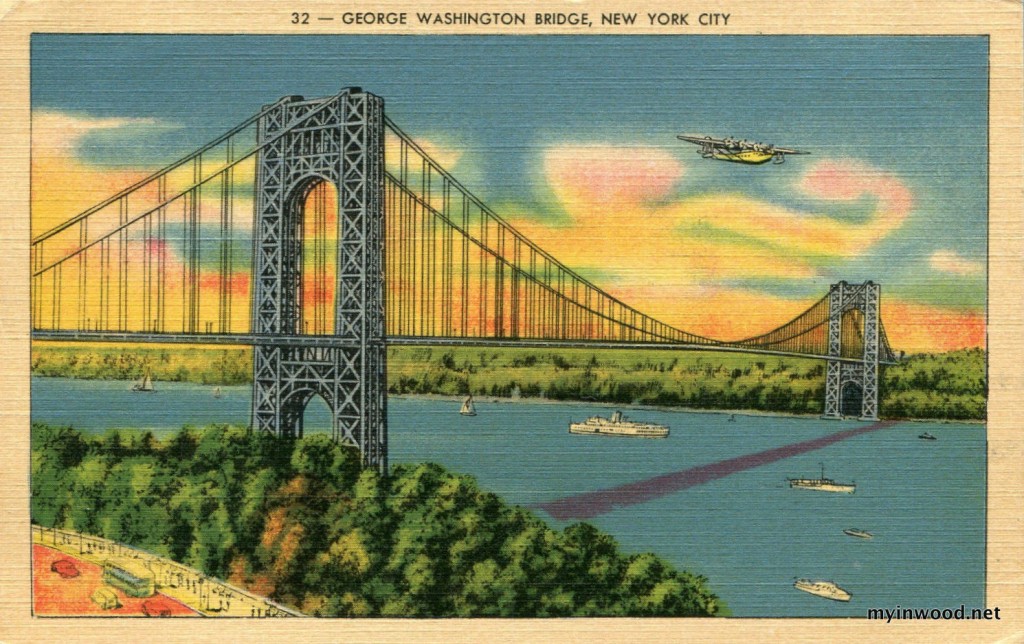

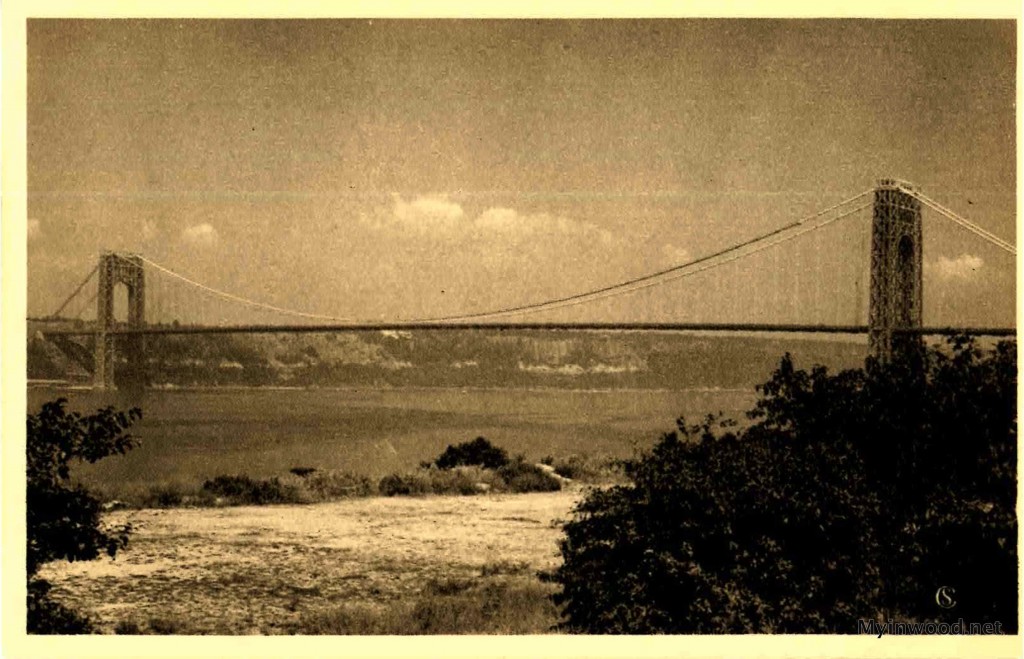

Previous to the cutting of the ship canal a curious phenomenon presented itself in the ebb and flow of Spuyten Duyvil Creek; for owing to the sinuosity and shallowness of that strait, its tides rarely kept pace with the larger volumes of water in the Hudson, and Harlem which it connected. To some extent this tidal peculiarity still exists. If we remember rightly an advantage to be gained by the construction of the canal would be the partial forestalling of a possible blockade of the New York Harbor and the passageway it would provide in a day of need for United States war vessels. Towards the last stages of its completion disaster befell the canal for abnormal high tides wrecked the bulkheads at the Kingsbridge Road and destroyed the temporary roadway that compromised the bulkhead. The canalling was completed by dredging-for the bulkhead was not restored.

![Depiction of the Spuyten Duyvil in a 1907 Singer Sewing machine card.]()

Depiction of the Spuyten Duyvil in a 1907 Singer Sewing machine card.

Two features of “interest” in natural history were disclosed by the cutting of the canal. One of these was the extensive lamination of peaty vegetable matter revealed in section to a considerable depth; the other was the exhuming of a mastodon’s tusk from the bed of an ancient bog. This was in the year 1885. The tusk is now in the American Museum. That particular remnant of a prehistoric kingdom is not, however, the only such of which Inwood can boast, for portions of the head of another Mastodon was unearthed-rather salvaged we should say-from a boy on the north side of Dyckman Street at the junction of Seaman Avenue when excavation work was carried to a depth of 21 feet below the sidewalk for a footing for the foundation of an apartment house. The tusks and skeletal remain of the mammoth still rest, perhaps, below the basement floor of #2 Seaman Avenue.

The name “Marble Hill” as applied to the extreme north portion of Manhattan Island forty years ago was derived from the character of the rock of which the hill is composed. A Revolutionary earthwork crowned the hill in a position to command the Kingsbridge. This work was known as “Fort Prince Charles,” its site and the marble of the hill are shown in a photograph taken by us in 1928.

In its passing from the rural to the urban we have witnessed the last appearance of certain forms of wildlife on northern Manhattan. The probable last foxes-there were two in 1892-one was minus a portion of his tail; the last mink we have his hide; and possibly the last raccoon we have noted, yet there are those who will, no doubt, be surprised to learn that wild rabbits still inhabit north Manhattan, and that opossums have been seen alive or dead at Kingsbridge, and Fieldstone within the past five years. All of these were oddities in their way-likely as the deer to be seen in unsuspected areas.

![Seaman and Payson Avenues near turn of the century. Seaman and Payson Avenues near turn of the century.]()

Seaman and Payson Avenues near turn of the century.

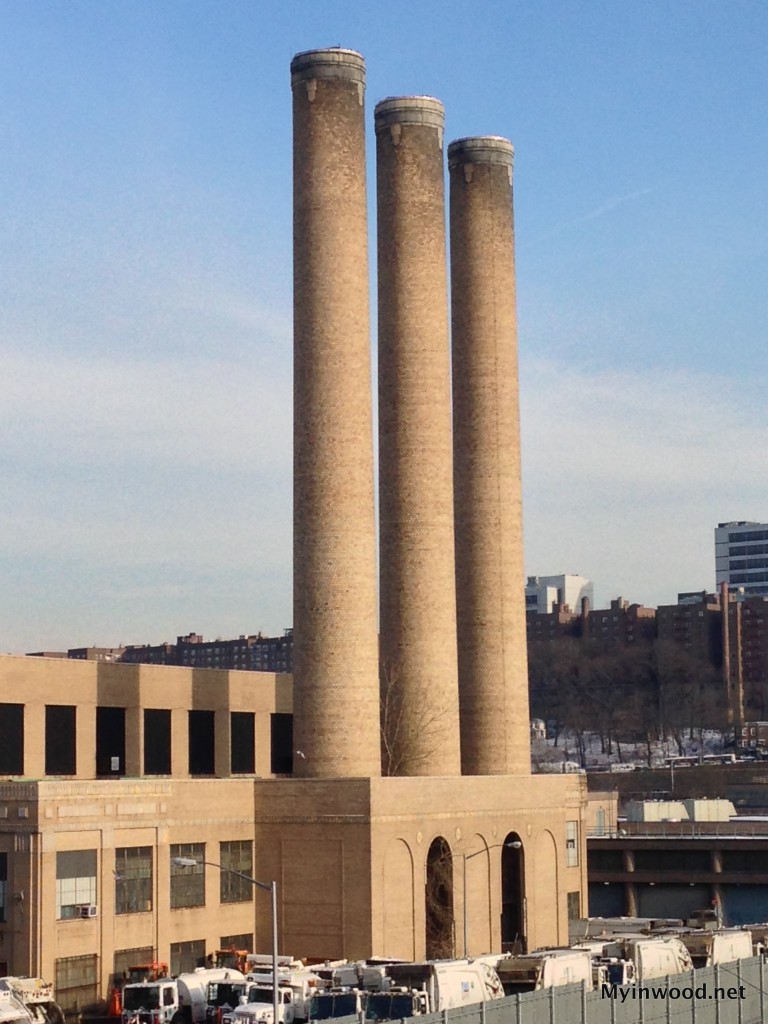

That section of Manhattan Island to which our recollections pertain has, of late, aside from its use as a place of residence for a vast population been the scene of at least five great developments, three of which in combination assure the maintenance of some of the original natural features of the locality. These are the parks bordering on the Hudson River and the ship canal. They compromise a continuous stretch of City owned grounds where areas may, in their development, prove and invaluable asset to the community at large. With the parklands may also be included the Baker Field, but opposed to these the extensive yards and shops of the new subway and a potential backset to an otherwise well formed region.

For more Inwood history, click here.

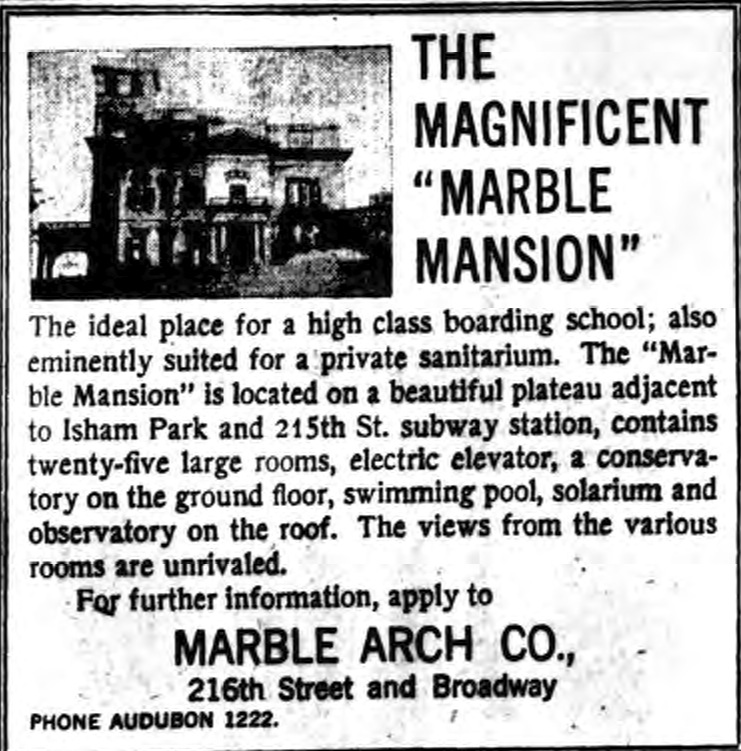

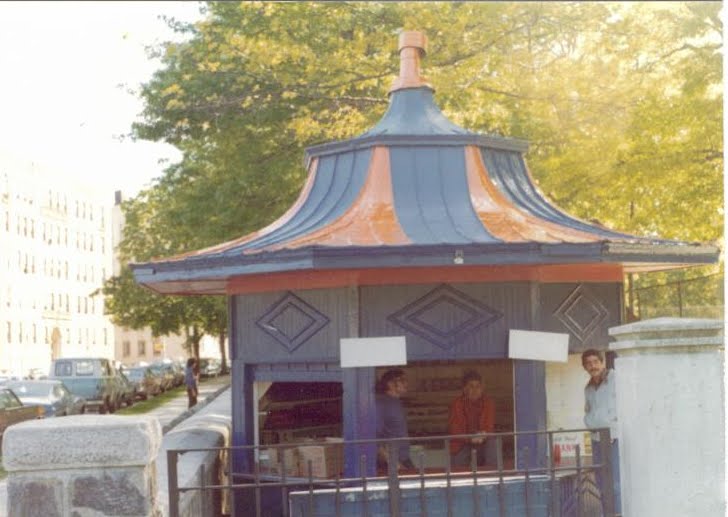

Designed in 1924 by the architectural team of Springsteen and Goldhammer, Isham Gardens was the brainchild of builder Conrad Glaser. Glaser envisioned an uptown utopia where middle class New Yorkers could live amidst a resort like atmosphere.

Designed in 1924 by the architectural team of Springsteen and Goldhammer, Isham Gardens was the brainchild of builder Conrad Glaser. Glaser envisioned an uptown utopia where middle class New Yorkers could live amidst a resort like atmosphere.