![Inwood Hill Park Inwood Hill Park]()

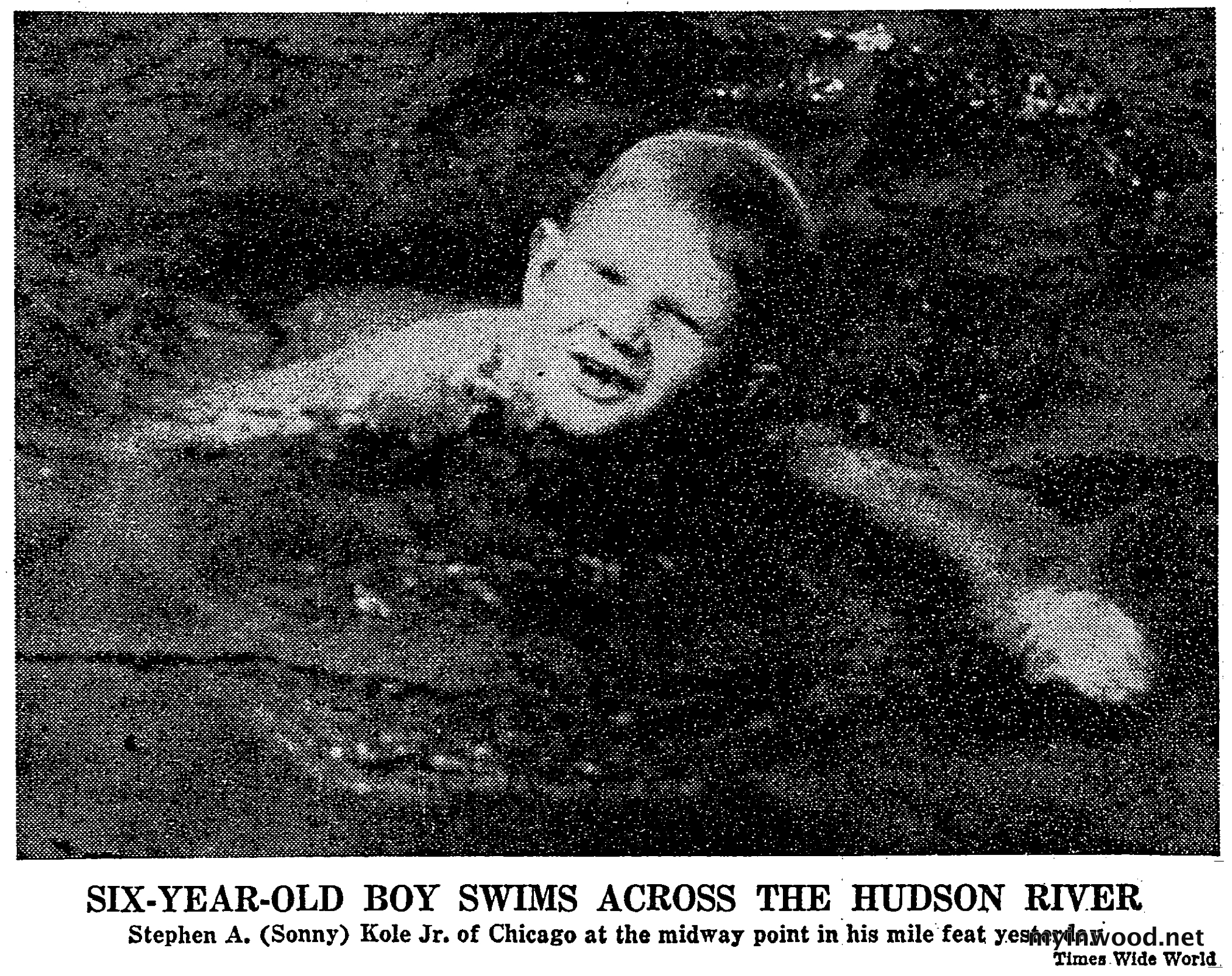

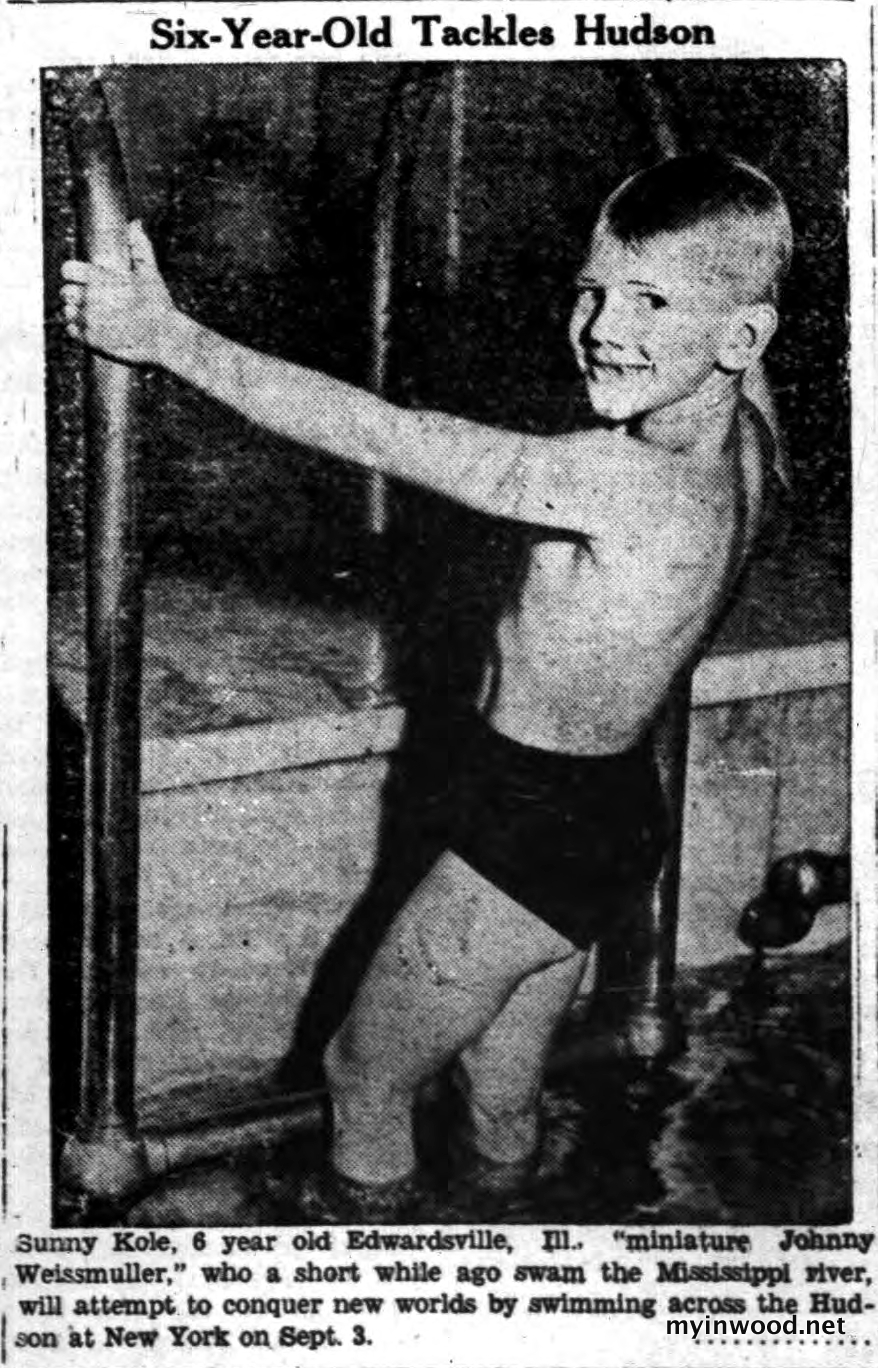

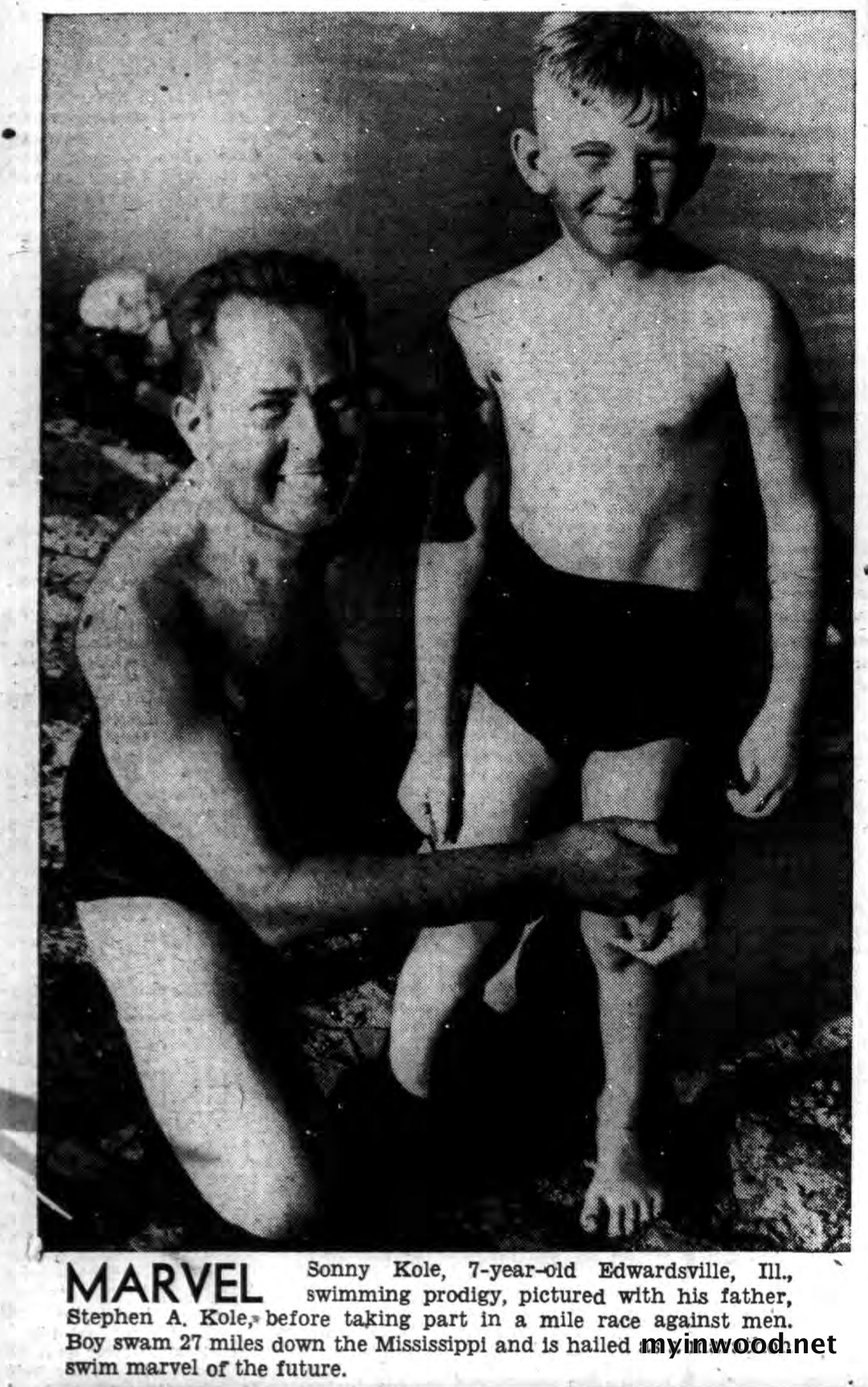

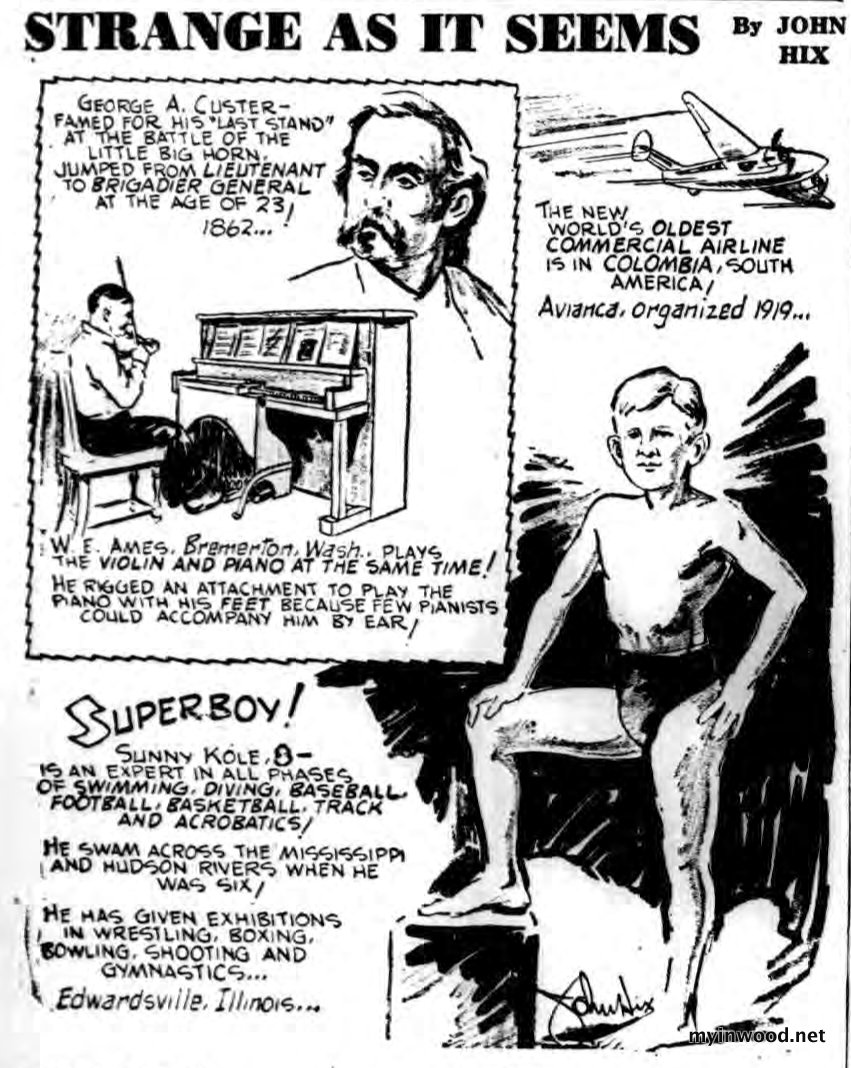

Inwood Hill Park

Inwood Hill is a 196-acre park located on the northern tip of Manhattan. The words “wild” and “untamed” are often used to describe the meandering trails, caves, cliffs and otherworldly geological formations that together make Inwood Hill so unique.

![Turn of the Century view of Inwood Hill and the Palisades from the Isham Estate, NYHS. Turn of the Century view of Inwood Hill and the Palisades from the Isham Estate, NYHS.]()

Turn of the Century view of Inwood Hill and the Palisades from the Isham Estate, NYHS.

![Inwood Hill and Henry Hudson bridge in 2014 Inwood Hill and Henry Hudson bridge in 2014]()

Inwood Hill and Henry Hudson bridge in 2014

The history of Inwood Hill, like that of the surrounding city, is equally fascinating and can be broken down into several periods:

- The Native, or pre-history, of Inwood Hill.

- Colonial village and Revolutionary War outpost.

- The age of the merchant class where grand estates lined the ridge.

- The era of institutions and asylums.

- Finally, the creation of Inwood Hill Park and on into the present.

Below you’ll find a rough timeline of a park many tourists will never see. An ancient, magical place seemingly removed from modern Manhattan.

![The Indian caves on Manhattan, from New York walk book : Suggestions for excursions afoot within a radius of fifty to one hundred miles of the city, 1923.]()

The Indian caves on Manhattan, from New York walk book : Suggestions for excursions afoot within a radius of fifty to one hundred miles of the city, 1923.

Pre-1609: Native Lenape use the current park site as a seasonal camp. One of the oldest of the Algonquin cultures, they were known as “The Ancient Ones.”

Today visitors to the park can view caves once used by the Lenape. Oyster shells from long forgotten Native feasts can be found under foot throughout the park.

![Depiction of Henry Hudson's voyage from 1929 print, NYPL. Depiction of Henry Hudson's voyage from 1929 print, NYPL.]()

Depiction of Henry Hudson’s voyage from 1929 print, NYPL.

1609: Explorer Henry Hudson passes Inwood Hill while travelling up the Hudson River. (While Hudson’s name has long been associated with the area, Verrazano likely sailed past Inwood Hill in 1524)

1626: Peter Minuit allegedly purchases the island of Manhattan from the Lenape for a handful of trinkets. Today a bronze plaque affixed to a large rock marks the site of the transaction.

1686: During an organized hunt early settlers exterminate the local wolf population. (Reginald Pelham Bolton, 1924)

1715: The last Native Americans to inhabit Inwood Hill “were induced to abandon the place.” (Inwood Hill Park on the Island of Manhattan, Reginald Pelham Bolton, 1934)

November 1776-1783: British and Hessian troops occupy Inwood Hill during the Revolutionary War. Today all that remains of Cock Fort Hill is a rocky outcropping on the north summit of the ridge where cannon were once trained to the north and east.

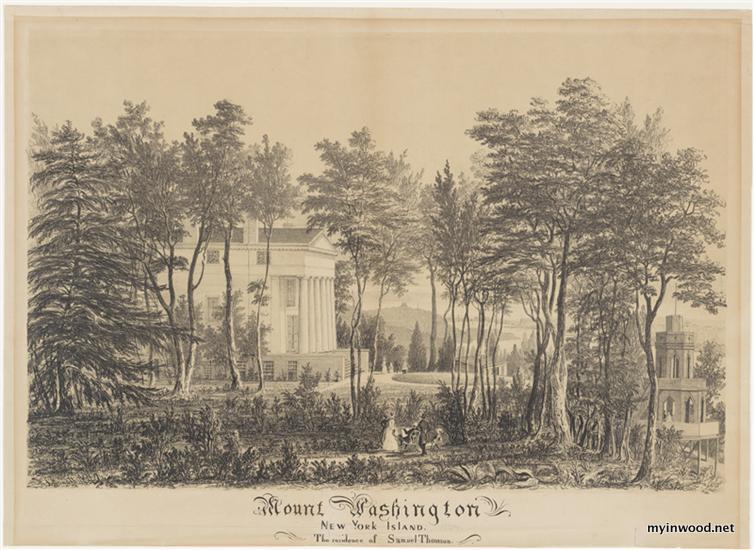

![Mount Washington residence of Samuel Thomson, by William S. Jewett 1847, MCNY. Mount Washington residence of Samuel Thomson, by William S. Jewett 1847, MCNY.]()

Mount Washington residence of Samuel Thomson, by William S. Jewett 1847, MCNY.

1840: Builder Samuel Thomson purchases eighty odd acres of land compromising the bulk of site we know as Inwood Hill. Thomson names the hill “Mount Washington.” The greater region was more commonly referred to as “Tubby Hook.”

![Railroad Bridge on Hudson and Spuyten Duyvil, January, 2009. Railroad Bridge on Hudson and Spuyten Duyvil, January, 2009.]()

Railroad bridge on Hudson and Spuyten Duyvil, January, 2009.

![Spuyten Duyvil Railroad bridge from old advertisement. Spuyten Duyvil Railroad bridge from old advertisement.]()

Spuyten Duyvil Railroad bridge from old advertisement.

1848: Railroad bridge is built over the Spuyten Duyvil. Members of the downtown merchant class begin to build summer residences in the newly accessible area.

“Cotton King” Frederick Talcott, dry goods magnate James McCreery, Macy’s co-founder Isidor Straus, Brooks Brother Elisha Brooks and others build grand homes on the hill.

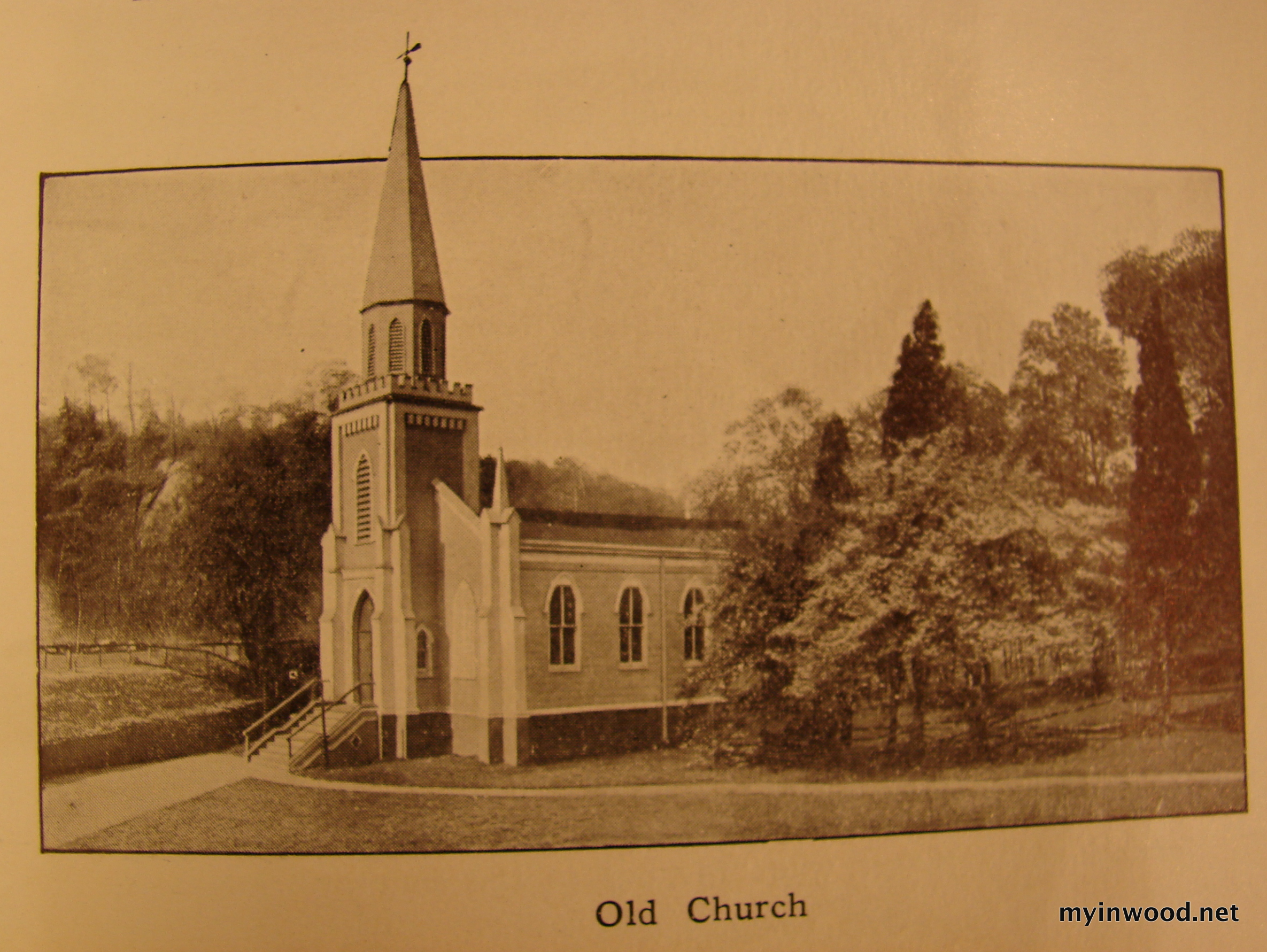

Late 1840’s: The name of the region, formerly known as “Tubby Hook,” is changed to Inwood.

According to an account published by C. Benjamin Richardson in 1864 the railroads inexplicably changed the sign at the local crossing. “The eye of the traveler on the Hudson River Rail Road is occasionally attracted by a new sign board at a station, and his ear by a new call by the conductor. The latest transportation is that of time-honored but unromantic, ‘Tubby Hook’ into ‘Inwood.’ Now ‘Inwood’ is a much prettier name…but it is not likely there ever was or would be another ‘Tubby Hook.’”

Many early sources also refer to the area as “Inwood on Hudson.”

1871: Train service is rerouted around the Spuyten Duyvil and down the Harlem River line leaving property owners cut off from downtown Manhattan. Members of New York’s merchant class abandon their summer residences.

In the absence of wealthy residents, Inwood Hill is given over to institutions and asylums. For decades it remains a bleak and desolate place of incarceration and suffering.

1880: Inwood chosen to host the 1883 World’s Fair. The plan was later abandoned.

!["Indian caves" in Inwood Hill Park. "Indian caves" in Inwood Hill Park.]()

“Indian caves” in Inwood Hill Park.

1890: Alexander Crawford Chenoweth discovers “Indian caves” not far from his Inwood home. Exploration of the caves unearths countless Native American artifacts.

![House of Mercy in 1932 photo. House of Mercy in 1932 photo.]()

House of Mercy in 1932 photo.

1891: Bishop Henry Codman Potter consecrates the Inwood House of Mercy on the ridge of Inwood Hill. This imposing home for wayward girls is the first of three institutions to open in what will later become Inwood Hill Park.

1891: Workers widening the Harlem River Ship Canal find the remains of a Mastodon. According to one account, “While laborers were working in the Harlem Canal, near Dyckman’s Creek, King’s Bridge, recently, they uncovered a mastodon’s tusk. Assistant Engineer Doerflinger had it removed with great care, and it was found to be in a great state of preservation. It was four feet long and six inches in diameter at the larger end. The tusk was sent to the curator of the geological department of the Museum of Natural History, New York.” (The Highland Democrat, December 19, 1891)

![Harlem Ship Canal under construction, photo by Gilman S. Stanton, circa 1893.]()

Harlem Ship Canal under construction, photo by Gilman S. Stanton, circa 1893.

June 17, 1895: The Harlem Ship Canal opens for marine traffic after decades of construction. The new canal, which connects the Harlem and Hudson Rivers, drastically alters the landscape—replacing a stream so shallow that it was referred to as the “wading place” by the Lenape.

1895: Andrew Haswell Green, the “Father of Greater New York,” makes a public plea that Inwood Hill should be acquired by the City for use as a park.

![House of Rest for Consumptives, 1910 postcard. House of Rest for Consumptives, 1910 postcard.]()

House of Rest for Consumptives, 1910 postcard.

1903: The House of Rest for Consumptives opens on Inwood Hill. Local residents opposed the establishment of a home for tuberculosis patients in their own backyard.

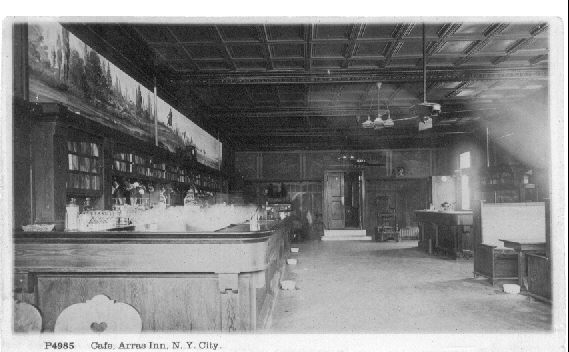

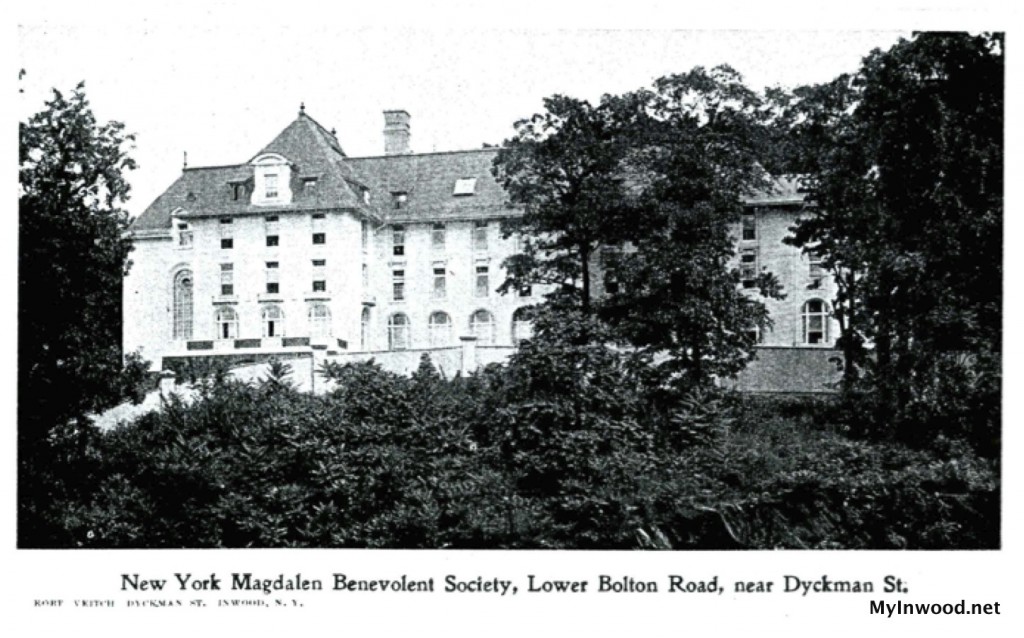

![Magdalen Society depicted in a penny postcard. Magdalen Society depicted in a penny postcard.]()

Magdalen Society depicted in a penny postcard.

1907: The Magdalen Asylum, a home for wayward girls, opens on the southern end of the park bordering Dyckman Street.

The institution is closed in 1920 after several of the girls succumb to mercury poisoning during treatments to cure venereal diseases. The building will later house the Jewish Memorial Hospital.

1909: Educator and philanthropist Thomas Davidson opens a camp for immigrants on Inwood Hill. His foundation, the Educational Alliance, focuses on educating young Jewish immigrants, teaching them the nuances of “American English,” and ultimately providing them with college educations so they, in turn, would be in a position to help their own people.

1910: The American Scenic and Historical Society fights to preserve Inwood Hill for park purposes. This after the City spent six years and $30,000 surveying the area in preparation for laying out streets.

![1912 Isham Park opening celebration poster. 1912 Isham Park opening celebration poster.]()

1912 Isham Park opening celebration poster.

1912: Nearby Isham Park opens after generous gift of land from the Isham family.

1912: New York based motion picture syndicates use Inwood Hill as a backdrop for silent western films. One news account describes the production of “Wild West” pictures “by the score” being shot on Inwood Hill. (New York Herald, July 21, 1912)

Film production will quickly move to Fort Lee, NJ before relocating to Hollywood.

![Inwood Hill amphitheatre proposal, New York Herald, May 17, 1914. Inwood Hill amphitheatre proposal, New York Herald, May 17, 1914.]()

Inwood Hill amphitheatre proposal, New York Herald, May 17, 1914.

1914: An open air amphitheatre is proposed for the northeastern slope of Inwood Hill. Think the Central Park Summerstage on a much grander scale, with bleachers lining the hill creating a Coliseum-like view.

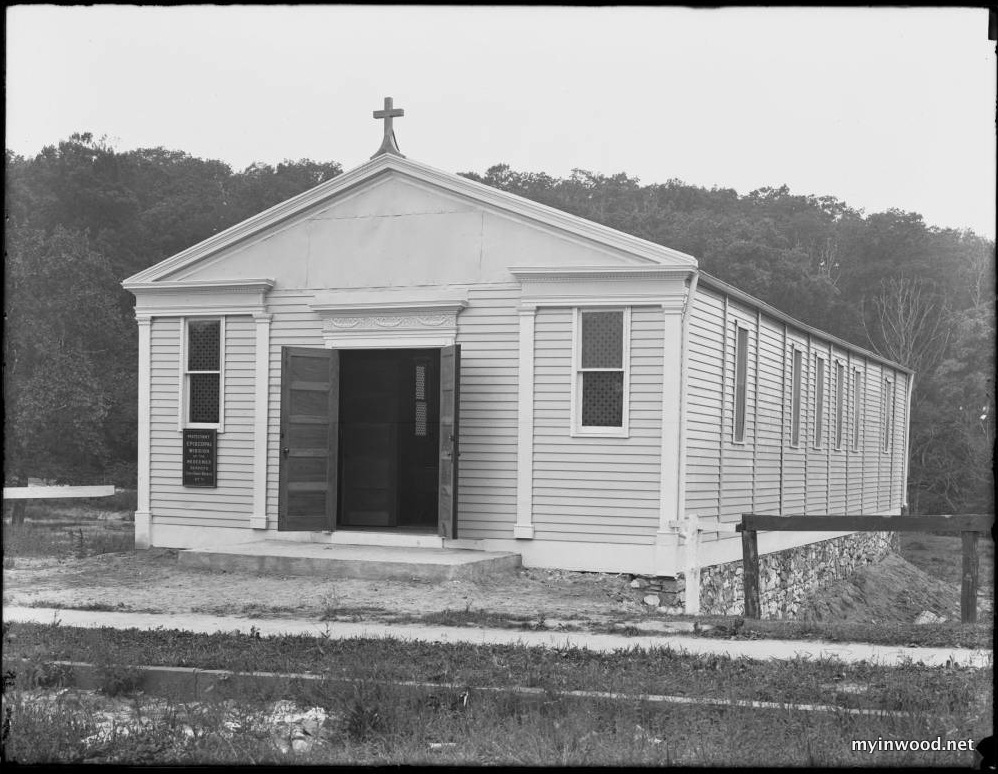

![Mission of the Redeemer, Isham Street and Seaman Avenue, New York City, September 5, 1915, NYHS. Mission of the Redeemer, Isham Street and Seaman Avenue, New York City, September 5, 1915, NYHS.]()

Mission of the Redeemer, Isham Street and Seaman Avenue, New York City, September 5, 1915, NYHS.

1915: (Date approximated) Mission of the Redeemer Church begins services inside the current Inwood Hill Park near the intersection of Seaman Avenue and Isham Street. In 1927 the church merges with Holy Trinity Episcopal Church currently located on 20 Cumming Street.

![Inwood Hill Park opens, New York Times, May 9, 1926. Inwood Hill Park opens, New York Times, May 9, 1926.]()

Inwood Hill Park opens, New York Times, May 9, 1926.

![Opening ceremonies of Inwood Hill Park, collection of Cole Thompson. Opening ceremonies of Inwood Hill Park, collection of Cole Thompson.]()

Opening ceremonies of Inwood Hill Park, collection of Cole Thompson.

May 8, 1926: Inwood Hill Park officially opens. Native Americans participate in the opening ceremonies attended by more than 1,000 New Yorkers. Newspapers noted that the majority of the spectators were children.

All told the City spends slightly over five million dollars on the land acquired from property owners and condemnation proceedings.

![New York Sun, January 21, 1926. New York Sun, January 21, 1926.]()

Indian Life Reservation, New York Sun, January 21, 1926.

1926: The “Indian Life Reservation” is created inside the newly opened park.

Native Americans who staffed the “reservation” came from different tribes, continents and backgrounds and played out the lives of the original Lenape inhabitants for a curious public.

![Western side of Inwood Hill Park along the Hudson River. Western side of Inwood Hill Park along the Hudson River-created using landfill in 1928.]()

The western side of Inwood Hill Park along the Hudson River is made of landfill.

![Western side of Inwood Hill park along the Hudson River. Western side of Inwood Hill park along the Hudson River.]()

Western side of Inwood Hill park along the Hudson River–created using landfill in 1928.

1928: Workers, using landfill, create 9 ½ new acres of park space along the Hudson River side of Inwood Hill Park.

According to a 1928 Parks Department report, “Filling operations are now under way in Inwood Hill Park along the Hudson River waterfront, extending north from Dyckman Street to about the center line of 212th Street, approximately 1400 feet in length. The fill is to extend to the U.S. bulkhead line, which is about 185 feet west of the right-of-way line of the New York Central Railroad. An approximate area of 9 ½ acres of new land has been added to the park and at some future time it is intended to lay out and plan this park area to harmonize with the surrounding park land.” (Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Manhattan, 1928)

![WPA Workers in Inwood Hill Park, 1938.]()

WPA Workers in Inwood Hill Park, 1938.

![WPA Workers in Inwood Hill Park, 193]()

WPA Workers in Inwood Hill Park, 1938

![Inwood Hill Park stairs in 2014. Inwood Hill Park stairs in 2014.]()

Inwood Hill Park stairs in 2014.

1930: Depression era work gangs begin improvements in the park. Trails are blazed and widened and near century old homes are destroyed in an effort to return the park to Nature.

According to a Parks Department annual report, “It has been the aim of the Park Department to retain Inwood Hill Park as far as practicable in its original state as a beautiful piece of natural woodland overlooking the Hudson River, and with this in view the work was begun of demolishing the old buildings which had outlived their usefulness and were rapidly becoming dilapidated. The plan suggested by Mr. Jules V. Burgevin, Landscape Architect of the Park Board, was carried out largely through the use of the three-day-a-week men employed under a special appropriation by the City to provide work for the unemployed. “(Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Manhattan, 1930)

1930: Drought affects trees throughout the city parks.

According an Annual Report of the Department of Parks, “In some of the parks we found it impossible to water the trees sufficiently on account of the inadequate water system and the difficulty of getting into the park with water wagons. This was especially the case in Riverside, Fort Washington and Inwood Hill Parks, there being no hydrants on the park side of Riverside Drive, therefore the watering of trees had to be done with the use of water barrels and tanks on horse-drawn trucks.” (Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Manhattan, 1930)

![Tulip Tree, Manhattan Parks Department annual report, 1930. Tulip Tree, Manhattan Parks Department annual report, 1930.]()

Tulip Tree, Manhattan Parks Department annual report, 1930.

![Repairs to Inwood Tulip Tree, Department of Parks Annual Report, 1930. Repairs to Inwood Tulip Tree, Department of Parks Annual Report, 1930.]()

Repairs to Inwood Tulip Tree, Department of Parks Annual Report, 1930.

1930: Parks Department tree surgeons use cement to repair damage to the old tulip tree. According to legend, it was under the ancient tulip that Native Americans traded the Island of Manhattan for a handful of trinkets and Guilders. (Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Manhattan, 1930)

![Glacial pothole in Inwood Hill Park. Glacial pothole in Inwood Hill Park.]()

Glacial pothole in Inwood Hill Park.

1931: Glacial potholes are discovered alongside a trail in a part of the park known as the “Clove” by Inwood resident Patrick Coghlan. After Parks Department workers clear away the undergrowth, geologists examine the site. Experts determine the phenomenon was the result of a glacial retreat tens of thousands of years ago.

1931: More relief for the unemployed.

900 laborers are assigned to clean up Highbridge and Inwood Hill Parks and assist in such work as “cutting down dead trees, removing rocks, cleaning roads and filling in depressions…” (Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Manhattan, 1931)

1931: Work crews continue demolition of structures, now derelict or inhabited by squatters, throughout the park. “Ninety-seven buildings, not including foundations, were demolished and removed.” (Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Manhattan, 1931)

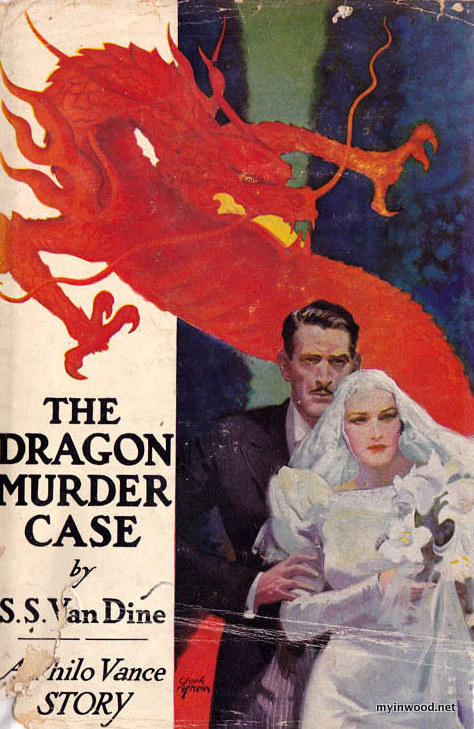

![The Dragon Murder Case takes place in a fictionalized Inwood Hill.]()

The Dragon Murder Case takes place in a fictionalized Inwood Hill.

1933: Mystery writer S.S. Van Dine uses Inwood Hill as the location for his novel, The Dragon Murder Case. The book is later made into a film. In the book the park’s glacial potholes turn out to be the entrances to caves inhabited by murderous dragons.

![Construction on Payson Avenue comfort station, April 24, 1934, Source NY Municipal Archives. Construction on Payson Avenue comfort station, April 24, 1934, (Source: NY Municipal Archives)]()

Construction on Payson Avenue comfort station, April 24, 1934, Source NY Municipal Archives.

![Play area and comfort station opens on Dyckman Street near Payson Avenue, August 8, 1934. (Source: NY Municipal Archives) Play area and comfort station opens on Dyckman Street near Payson Avenue, August 8, 1934. (Source: NY Municipal Archives)]()

Play area and comfort station opens on Dyckman Street near Payson Avenue, August 8, 1934. (Source: NY Municipal Archives)

August 8, 1934: Playground and comfort station open near Dyckman Street and Payson Avenue.

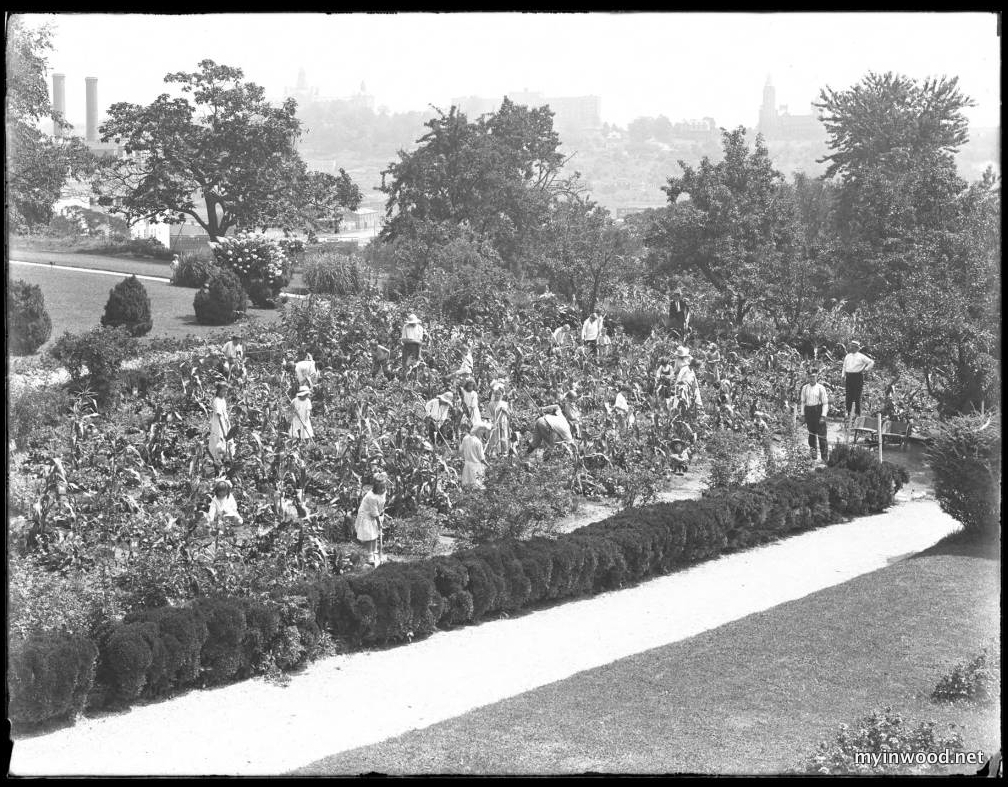

![Summer day camp, Inwood Hill Park, August 20, 1934 , from NYC Parks Dept. Summer day camp, Inwood Hill Park, August 20, 1934 , from NYC Parks Dept.]()

Summer day camp, Inwood Hill Park, August 20, 1934 , from NYC Parks Dept.

1934: Summer camp opens for New York City youngsters in Inwood Hill Park.

According to a history on the Parks Department website, “Following the consolidation of the City’s parks system under Commissioner Robert Moses in January 1934, the Parks Department announced plans to establish day camps for 2,500 children with both an educational and recreational mission. The activities were jointly managed by Parks Department play leaders, as well as staff from the Board of Education. The day camp depicted here was at the northern tip of Manhattan near the ‘old House of Mercy,’ and afforded views from the bluffs overlooking the Hudson. The programs consisted of games, nature and geology studies, arts and crafts, story telling, drama, and community singing among various activities, and children were provided free transportation and lunch.”

![Harry Houdini Hinson killed in sled accident, New York Times, February 18, 1934. Harry Houdini Hinson killed in sled accident, New York Times, February 18, 1934.]()

Harry Houdini Hinson killed in sledding accident, New York Times, February 18, 1934.

1934: Houdini’s nephew, Harry Houdini Hinson, is killed in a sledding accident near his aunt, Bess Houdini’s, home on 67 Payson Avenue.

May 21, 1935: The Department of Parks announces the opening of bids for the construction of the Henry Hudson Bridge across the Spuyten Duyvil.

Amazingly, construction lasts just one year and the project, under the leadership of Robert Moses, comes in under budget.

![Henry Hudson Bridge opens, New York Times December 11, 1936. Henry Hudson Bridge opens, New York Times December 11, 1936.]()

Henry Hudson Bridge opens, New York Times December 11, 1936.

![Henry Hudson Bridge postcard. (Collection of Cole Thompson) Henry Hudson Bridge postcard. (Collection of Cole Thompson)]()

Henry Hudson Bridge postcard. (Collection of Cole Thompson)

![Henry Hudson Bridge postcard (Collection of Cole Thompson) Henry Hudson Bridge postcard (Collection of Cole Thompson)]()

Henry Hudson Bridge postcard. (Collection of Cole Thompson)

1936: Henry Hudson Bridge opens for traffic.

![1935 photo shows the Spuyten Duyvil just before the final cut. 1935 photo shows the Spuyten Duyvil just before the final cut.]()

1935 photo shows the Spuyten Duyvil just before the final cut.

![2013 satellite image of the Spuyten Duyvil from Google Maps. 2013 satellite image of the Spuyten Duyvil from Google Maps.]()

2013 satellite image of the Spuyten Duyvil from Google Maps.

1936: Engineers make a direct cut through the peninsula that once extended from the cliff today marked by the “Columbia C.” The tip of the former peninsula, now an “island,” is today home to the Inwood Hill Park Urban Ecology Center.

![Princess Naomi in front of Indian caves in Inwood Hill Park. (New York Times, Nov. 15, 1936. Princess Naomi in front of Indian caves in Inwood Hill Park. (New York Times, Nov. 15, 1936.]()

Princess Naomi in front of Indian caves in Inwood Hill Park. (New York Times, Nov. 15, 1936)

December 1936: Robert Moses evicts all “squatters” from the park. Eviction notices are issued to the Inwood Pottery Works and Dyckman Institute curator Naomie Kennedy (commonly known as Princess Naomie)

“The hullabaloo,” Robert Moses would write, “about disturbing the princess, the kiln, the old tulip tree, and other flora and fauna was terrific.” (Public Works, 1970)

![1893 photo by Ed Wenzel shows area long before the landfill project. 1893 photo by Ed Wenzel shows area long before the landfill project.]()

1893 photo by Ed Wenzel shows area long before the landfill project.

![Boats moored in Inwood Hill basin in 1935. The site of the Gaelic field housed a marina before being covered with landfill.]()

Boats moored in Inwood Hill basin in 1935. The site of the Gaelic field housed a marina before being covered with landfill.

![A newly planted Gaelic field shortly after the landfill project, courtesy Betty Lee. A newly planted Gaelic field shortly after the landfill project, courtesy Betty Lee.]()

A newly planted Gaelic field shortly after the landfill project, courtesy Betty Lee.

![Gaelic field today. Gaelic field today.]()

Gaelic field today.

June 11, 1936: Parks Department announces plan to use landfill to add 24 acres of land to the park in an area now commonly known as the Gaelic field. The plan coincides with the War Department’s decision to straighten the Spuyten Duyvil.

According to a Park’s Department press release, “Upon the completion of the reclamation in the new area, the Park Department will have provided the public with a new yacht basin capable of caring for well over 100 boats. Adjacent to the yacht basin will be a new clubhouse and roadways and a parking area capable of taking care of 300 cars. There will be an additional large recreational area including a baseball diamond. The whole plan is pleasing in appearance, will be well landscaped and amply provided with walks and roadways. It is anticipated that these additional park facilities will be subjected to intense use.” (Parks Department press release, June 11, 1936)

![The end of the mighty Inwood tulip, 1930's, NYHS. The end of the mighty Inwood tulip, 1930's, NYHS.]()

The end of the mighty Inwood tulip, 1930′s, NYHS.

1938: Inwood’s famed tulip tree dies. The tree was 280 years old.

![Bridge across railroad tracks in Inwood Hill Park. Bridge across railroad tracks in Inwood Hill Park.]()

Bridge across railroad tracks in Inwood Hill Park.

January 26, 1938: “Plans and bids on construction of a pedestrian bridge over the New York Central Railroad tracks in Inwood Hill Park by Henry Hudson Parkway Authority.” (Parks Department press release, January 26, 1938)

9:50 am, January 26, 1938: Brooklyn resident Harry E. Butcher, a chauffer for the Safety Fire Extinguisher Company, drives the seven millionth car to pass over the Henry Hudson Bridge. The Henry Hudson Parkway Authority awards Mr. Butcher a fifty-trip booklet of toll passes. (Parks Department press release, January 28, 1938)

![Upper deck of the Henry Hudson Bridge opens to traffic, New York Times, May 7, 1938. Upper deck of the Henry Hudson Bridge opens to traffic, New York Times, May 7, 1938.]()

Upper deck of the Henry Hudson Bridge opens to traffic, New York Times, May 7, 1938.

May 7, 1938: Upper roadbed of the Henry Hudson Bridge opens for traffic.

![Yacht basin proposal, New York Times, May 7, 1939. Yacht basin proposal, New York Times, May 7, 1939.]()

Yacht basin proposal, New York Times, May 7, 1939.

1939: Parks Department again announces plans for a new yacht basin.

According to the New York Times, “The new neck out into the Harlem River becomes an extension of 218th Street. Passing Baker Field and the Columbia University crew house and shell sheds, the automobiles of yachtsmen will proceed along a riprapped isthmus to a special parking area near the basin and the dock master’s house that are soon to be erected. Two inverted L-shaped bulkheads have been designed on the blueprints to accommodate the berths for forty-five cruisers up to fifty feet or so over-all.” (New York Times, May 7, 1939)

The project is never completed.

June 22, 1939: Letter to New York Times complains of “deplorable” conditions in Inwood Hill Park.

The park, wrote F.L.S., “has become a stomping ground for all sorts of vandals, who break and carry off blooming shrubs, flowers and even branches within reach.”

“The park is littered with old newspapers and refuse,” the letter continues. “It is overgrown with poison ivy and ragweed. It has no benches, drinking fountains or toilets. And all that, in spite of the fact that the park is visited daily by hundreds of children. “

November 26, 1940: “The Department of Parks announces that plans are being made for a marker to be erected on the site of Cock’s Hill Fort, Inwood Hill Park… Preliminary sketches for the proposed memorial development of the site, which is roughly 80 feet square, indicate a 75 foot flagstaff supported by a simple granite base upon which a suitable inscription will be incised. Comfortable park benches will be arranged about the memorial under the fine old trees which shade the site.” (Parks Department press release, November 26, 1940)

The project was never realized. Today the site remains unmarked.

![Tennis courts and ballfield open in Inwood Hill Park, 1941, Source, NY Municipal Archives. Tennis courts and ballfield open in Inwood Hill Park, 1941, Source, NY Municipal Archives.]()

Tennis courts and ballfield open in Inwood Hill Park, 1941, Source, NY Municipal Archives.

1941: Tennis courts and ball fields open on eastern side of Inwood Hill Park along Seaman Avenue.

![New York Post, March 30, 1948 New York Post, March 30, 1948]()

New York Post, March 30, 1948

March 1948: The Parks Department, for the first time, opens Inwood Hill Park to bicycles and roller skates.

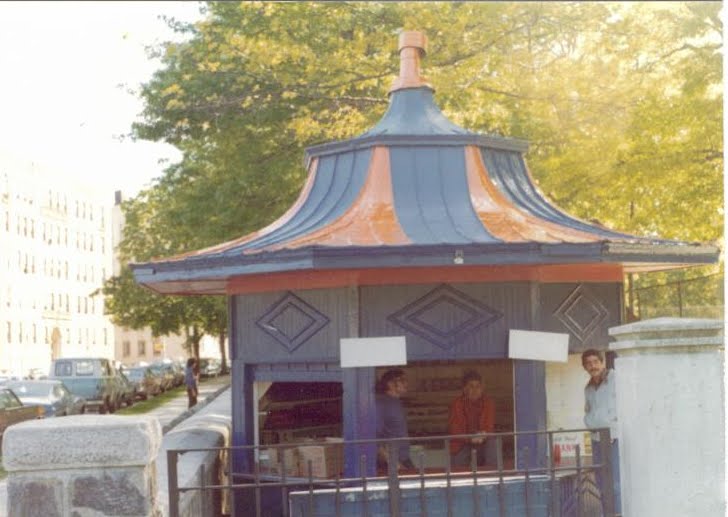

![Inwood Hill Park Concession stand on the corner of Isham and Seaman in 1977. Louise & Frank Yannaco pictured with merchandise in the background. (Photo courtesy Frank Yannaco) Inwood Hill Park Concession stand on the corner of Isham and Seaman in 1977. Louise & Frank Yannaco pictured with merchandise in the background. (Photo courtesy Frank Yannaco)]()

Inwood Hill Park Concession stand on the corner of Isham and Seaman in 1977. Louise & Frank Yannaco pictured with merchandise in the background. (Photo courtesy Frank Yannaco)

![Inwood Hill Park Concession stand on the corner of Isham and Seaman in 1977. Louise & Frank Yannaco pictured with merchandise in the background. (Photo courtesy Frank Yannaco) Yannaco family poses for photo in front of the concession stand in 1977. (Photo courtesy Frank Yannaco)]()

Yannaco family poses for photo in front of the concession stand in 1977. (Photo courtesy Frank Yannaco)

1950′s-1988: The Yannaco family operates a concession stand inside the Isham Street entrance to Inwood Hill Park.

![Boulder in Inwood Hill Park marks the site of the old tulip tree. Boulder in Inwood Hill Park marks the site of the old tulip tree.]()

Boulder in Inwood Hill Park marks the site of the old tulip tree.

1954: The Peter Minuit Post of the American Legion dedicated a plaque marking the location of the fabled Inwood Tulip Tree. According to the plaque the site was also the location of the alleged 1626 transaction between Peter Minuit and the Lenape for the purchase of Manhattan.

July 20, 1956: Free puppet show at the playground on Isham Street and Seaman Avenue. Description: “Miss Pink Elephant, the Ballerina heroine of ‘Happy the Humbug,’ has a remarkable talent—crying strawberry tears from which delicious ice cream sodas can be concocted. Children secretly sympathize with the villains, Cock and Bull, who kidnap her in order to profit by her unusual gift. However, as the plot unfolds, they understand why Happy must rescue her and want to see the villains outwitted.” (Parks Department press release, July 20, 1956)

![A fallen "Lindsay Light" in Inwood Hill Park. A fallen "Lindsay Light" in Inwood Hill Park.]()

A fallen “Lindsay Light” in Inwood Hill Park.

1966-1973: Lamp posts are erected throughout the park during the administration of Mayor John Lindsay. The lights are quickly vandalized. The posts come to be called “Lindsay Lights.”

November, 1971: 100 National Guardsmen are deployed in Inwood Hill Park to help a short-staffed parks department clear dead trees and trash.

According to Daniel Nelson, an official of the union representing park workers, “The city has no money now, the park needs rehabilitation, and the guardsmen need the experience.” (New York Times, November 13, 1971)

April 1972: National Guardsmen ordered to leave after neighborhood protests. Residents claim that heavy construction equipment is destroying the park’s fragile ecology.

1992: Legislation is introduced by Council Member Stanley Michaels to name the natural areas of the park “Shorakapok” in honor of the Lenape.

1995: Inwood Hill Park Urban Ecology Center opens

2002: Urban Park Rangers begin a five-year project to reintroduce Bald Eagles into the park.

![Storm damage in Inwood Hill Park in aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Storm damage in Inwood Hill Park in aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.]()

Storm damage in Inwood Hill Park in aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.

![Inwood Hill Park Urban Ecology Center in 2014. Inwood Hill Park Urban Ecology Center in 2014.]()

Inwood Hill Park Urban Ecology Center in 2014.

2012: Hurricane Sandy knocks down trees and floods the Inwood Hill Park Urban Ecology Center. Two years later the facility remains a ruin.

![Muscota Marsh Park in 2014. Muscota Marsh Park in 2014.]()

Muscota Marsh Park in 2014.

January 2014: One-acre Muscota Marsh Park opens next to Columbia University’s Baker Athletic Complex.

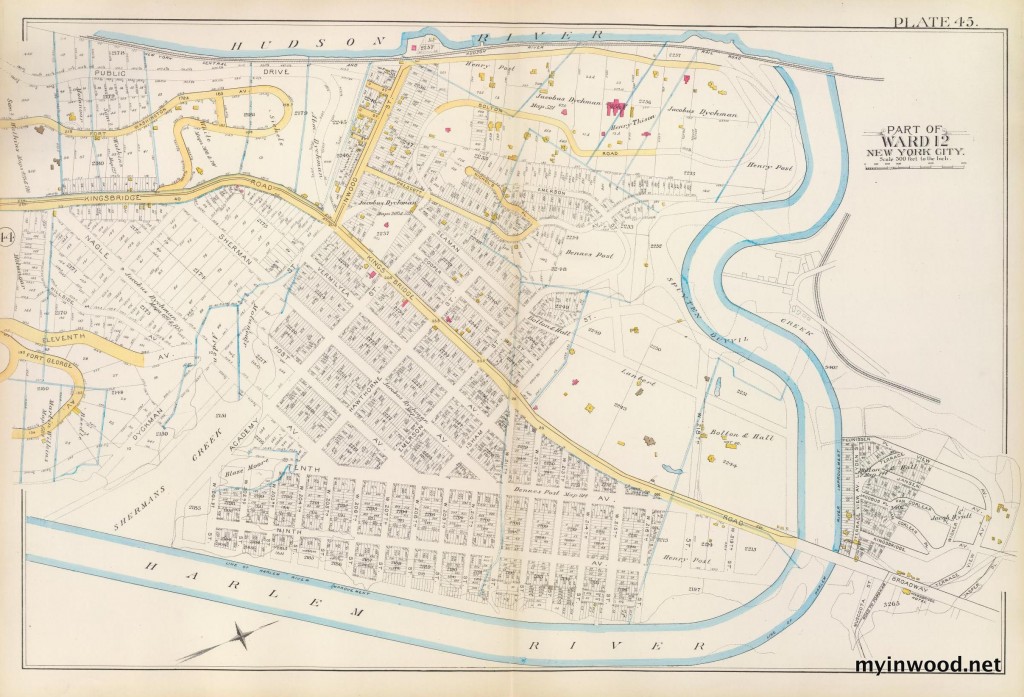

Now that we’ve finished our magical history tour of Inwood Hill Park its time for you to boot up and hit the trails. Below are some of my favorite maps of the park. why not start your own historical exploration? Let me know what you find.

(Click any map to enlarge)

![1879 real estate map by G.W. Bromley and Company. 1879 real estate map by G.W. Bromley and Company.]()

1879 real estate map by G.W. Bromley and Company.

![1891 map by G.W. Bromley and Company. 1891 map by G.W. Bromley and Company.]()

1891 map by G.W. Bromley and Company.

![Inwood Hill map, circa 1910. Inwood Hill map, circa 1910.]()

Inwood Hill map, circa 1910.

![1925 Inwood Hil map. 1925 Inwood Hil map.]()

1925 Inwood Hil map.

![Inwood Hill Park map, Inwood Hill Park on the island of Manhattan, Reginald Bolton, 1932. Inwood Hill Park Map, Inwood Hill Park on the island of Manhattan, Reginald Bolton, 1932.]()

Inwood Hill Park map, Inwood Hill Park on the island of Manhattan, Reginald Bolton, 1932.

![Inwood Hill trail map from 1970's. One of my favorites as the trails have changed very little. Inwood Hill trail map from 1970's. One of my favorites as the trails have changed very little.]()

Inwood Hill trail map from 1970′s. One of my favorites as the trails have changed very little.